Brisk Hematochezia in Cirrhosis

Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Rectal Variceal Bleeding

Rectal varices (RV) are dilated submocsal portosystemic collateral veins present at a minimum of four centimeters proximal to the anal verge. RV are common in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, with an estimated incidence of 38%-56%. However, rectal variceal bleeding is rare, occurring in only 0.5%-5% of patients with RV. The gold standard for RV diagnosis is endoscopy. Although direct visualization with endoscopy is the most common method for diagnosing RV, endoscopic ultrasound has a higher accurary rate (85% vs 45%).

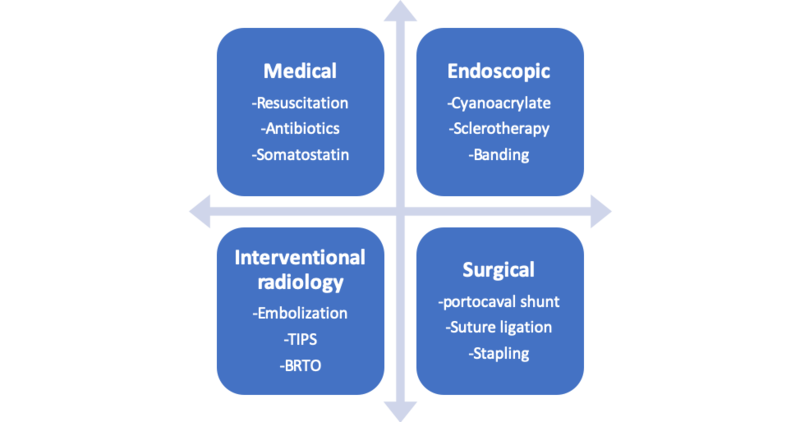

Figure 1 - Endoscopic view of rectal varices.

Taken from: Successful Treatment of Bleeding Rectal Varices with Occluded Antegrade Transvenous Obliteration. ACG Case Reports Journal 2018.

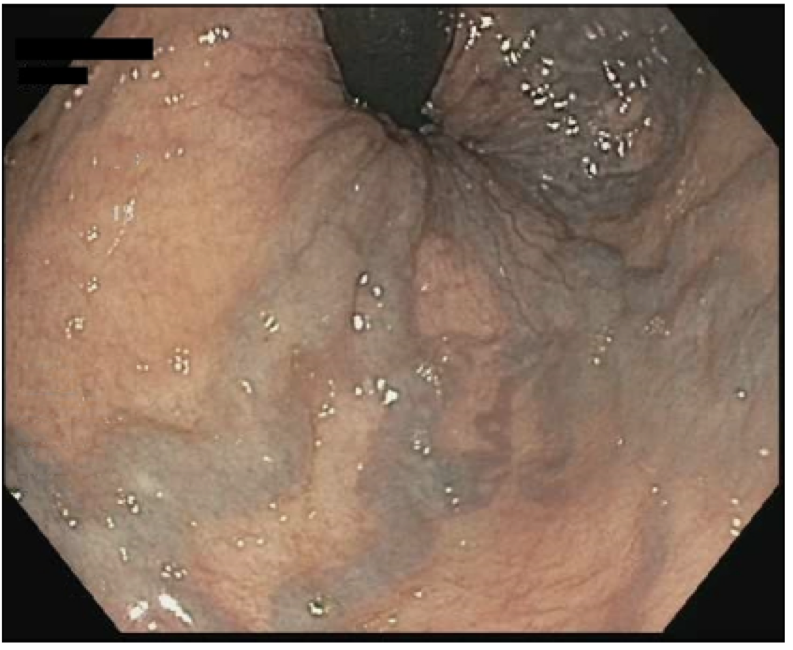

Figure 2 - Endoscopic ultrasound view of rectal varices.

Taken from: EUS-Guided Coiling of Rectal Varices. VideoGIE 2017.

Management of Rectal Variceal Bleeding

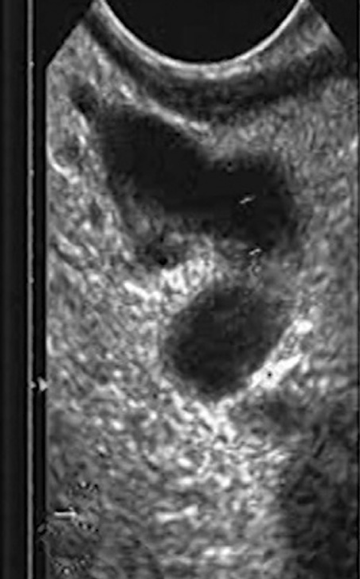

The cornerstones of RV bleeding management are medical, endoscopic, interventional radiology-based, and surgical. Standard medical management for portal hypertensive bleeding—resuscitation, gram-negative antibiotic coverage for infection prophylaxis, and a somatostatin analog such as octreotide to reduce portal pressures—are recommended. Endoscopic options for hemostasis include the following: cyanoacrylate injection, sclerotherapy injection, and band ligation. Cyanoacrylate carries a risk of embolization and sepsis. This risk can be minimized by coupling this method with EUS guided coil embolization. Risks of sclerotherapy also include embolization, and band ulcers can develop as a complication of banding.

Interventional radiology procedures for managing RV bleeding include the following: embolization, transjugular intra-hepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO). Embolization can be performed solo or in combination with TIPS. While BRTO does not decrease portal pressures as TIPS does, benefits of BRTO over TIPS are that it is less invasive, can be performed in those with minimal hepatic reserve, and does not increase the risk of hepatic encephalopathy as TIPS does. BRTO can, however, cause worsening of esophageal varices by eliminating a shunt. Surgical management is often challenging due to the severe liver disease of affected patients. Portocaval shunt creation is one surgical option, although there is a reported 80% mortality within two months of this surgery. Other options include suture ligation or rectal variceal stapling; the latter has a higher reported success rate than the former.

Figure 3 - Therapeutic modalities for rectal variceal bleeding

BRTO: balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.