Hepatic Abscesses: Where Hepatology meets Infectious Disease

Understanding the etiology of a hepatic abscess

First, try to identify the cause of the hepatic abscess. This will help elucidate what additional work up is needed aside from just starting antibiotics. While it’s important to treat the issue at hand, it is not enough to stop there. You need to ask, “WHY?”

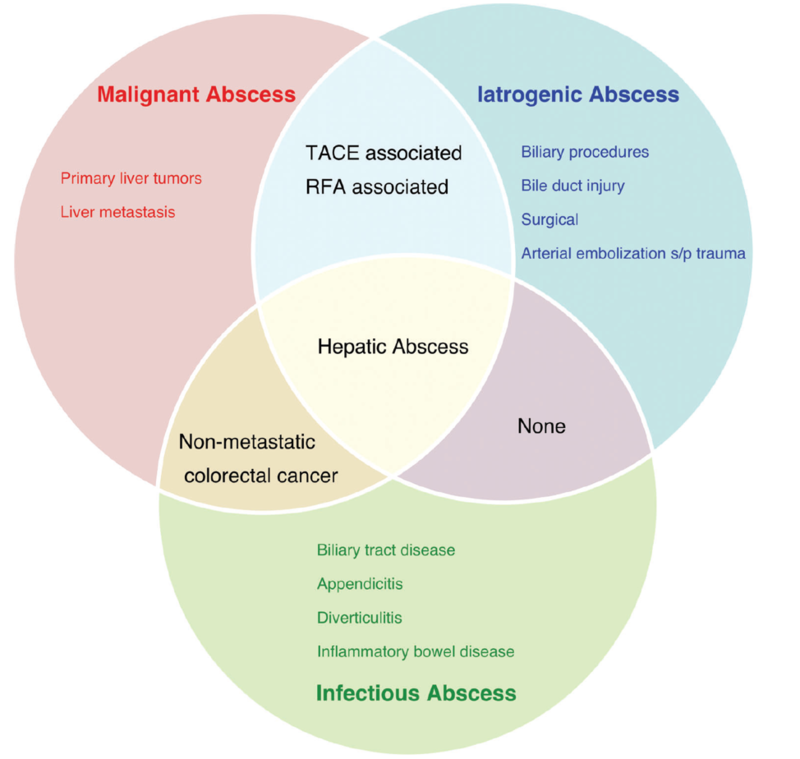

A review by Mavilia et al provides a good framework about different etiologies of hepatic abscesses: infectious, malignant, and iatrogenic causes.

Figure 1 - Categorization of hepatic abscesses

Taken from: Mavilia M, Molina M, Wu G. The Evolving Nature of Hepatic Abscess: A Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016

Infectious abscess:

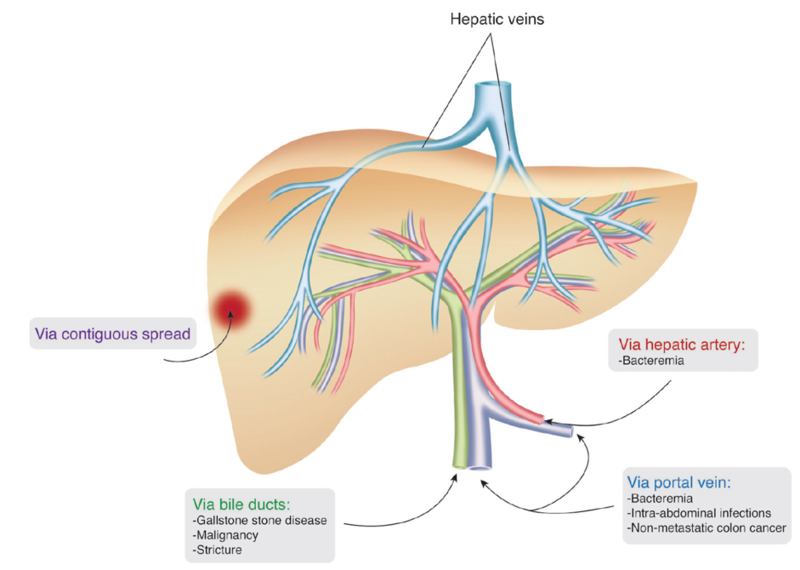

A pyogenic liver abscess most commonly develops via contiguous spread from surrounding infected tissues (i.e. biliary infection via direct spread), spread via portal circulation (i.e. leakage of intra-abdominal bowel contents with spread to portal circulation), or from arterial hematogenous seeding (i.e. bacteremia).

Figure 2 - Routes of infection

Taken from: Mavilia M, Molina M, Wu G. The Evolving Nature of Hepatic Abscess: A Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016

Malignant abscess:

A malignant abscess can be seen in the setting of secondary infection of a primary liver tumor (i.e. HCC developing in an area of central necrosis that can then become infected with bacteria, HCC causing biliary obstruction), secondary infection of liver metastases, or superinfection of spontaneous necrosis.

Iatrogenic abscess:

Several procedures have been associated with an increased risk of hepatic abscess formation. TACE/RFA can induce necrosis of tumor and surrounding liver tissue, which may then serve as a nidus for infection. Surgical procedures can potentially cause ischemic necrosis, biliary strictures, or hematomas in the liver which can all predispose to possible hepatic abscess formation. In addition, biliary procedures can allow for ascending infection leading to development of hepatic abscesses.

Diagnosis:

After thinking through the etiology and risk factors for possible hepatic abscess, diagnosis is generally achieved via imaging. Typically, ultrasound and/or CT are used for identification of a liver abscess, with CT as a more sensitive modality.

CT or ultrasound guided drainage should be attempted to confirm the diagnosis and to identify the responsible pathogen(s).

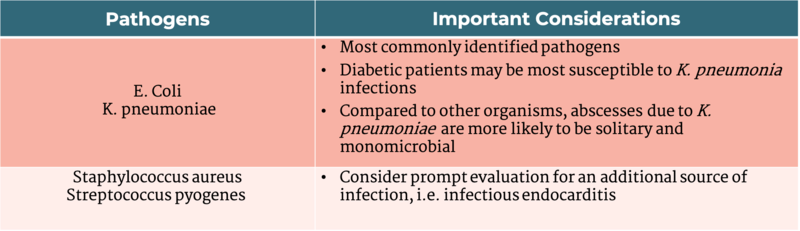

Types of bacteria seen with hepatic abscess:

Most pyogenic liver abscesses tend to be polymicrobial, with mixed enteric and anaerobic species as the most common pathogens. Given the variability of causes and geographic differences, a microbiological diagnosis is essential in most cases.

Table 1- Common pathogens in pyogenic liver abscess

Adapted from: Davis J, McDonald M. Pyogenic liver abscess. UpToDate. Sep 2020.

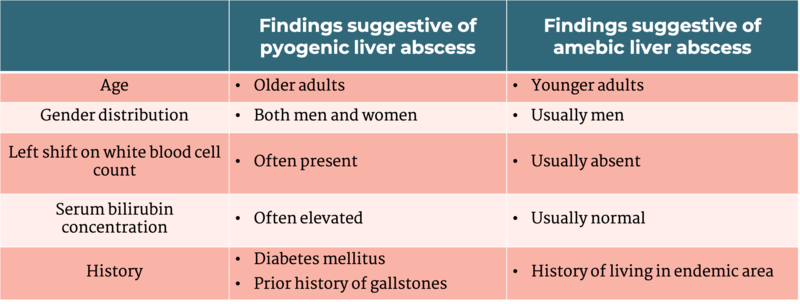

When to think about amebic liver abscesses:

Entamoeba histolytica abscesses should be considered in patients who may not have risk factors for pyogenic abscess. Risk factors for pyogenic abscesses include recent surgery, abdominal infection, recent biliary procedure, or systemic infection with positive blood cultures. Epidemiologic risk factors for amebic abscesses include living in endemic areas including India, Mexico, Africa, Central and South America.

On imaging, 70-80% of amebic abscesses are solitary subcapsular lesions. Serology and antigen detection can also aid in the diagnosis as 90% of patients with amebic liver abscess develop antibodies by time of presentation. In cases where further diagnosis is needed, aspiration can be performed but is not necessary for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. Aspiration can yield a brown fluid consisting of necrotic hepatocytes, often compared to ‘anchovy paste.’ Antigen testing and/or PCR on aspirated fluid can be helpful in solidifying the diagnosis, if needed. Most cases of amebic liver abscesses can be treated with metronidazole or tinidazole.

Table 2 - Characteristics of pyogenic vs amebic liver abscess

Taken from: Leder K, Weller P. Extraintestinal Entamoeba histolytica amebiasis. UpToDate. Sep 2020.

Entamoeba or Echinococcus?

Any mass occupying lesion can clinically be mistaken for an echinococcal cyst. Symptoms of echinococcus generally do not present until a cyst reaches 10 cm. If enlarged, cysts can cause hepatomegaly, RUQ pain, venous obstruction from mass effect, cholestasis or even portal hypertension. Hydatid cysts can generally be seen on ultrasound, but CT or MRI may be more helpful in establishing the number of cysts, presence of daughter cysts and presence of ruptured or calcified cysts. Management options include drug therapy with albendazole, surgery, or percutaneous management.

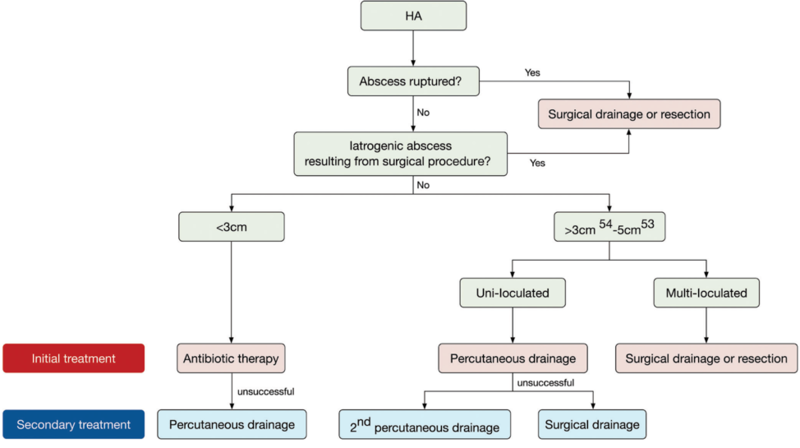

Treatment

Management should be determined with a multidisciplinary team as it can involve interventional treatment, specific pathogen testing and/ or even surgical treatment. Abscess size and consistency should be considered when choosing a strategy. Below is a proposed figure outlining treatment strategies of hepatic abscesses.

Figure 3- Hepatic abscess treatment algorithm

Taken from: Mavilia M, Molina M, Wu G. The Evolving Nature of Hepatic Abscess: A Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016

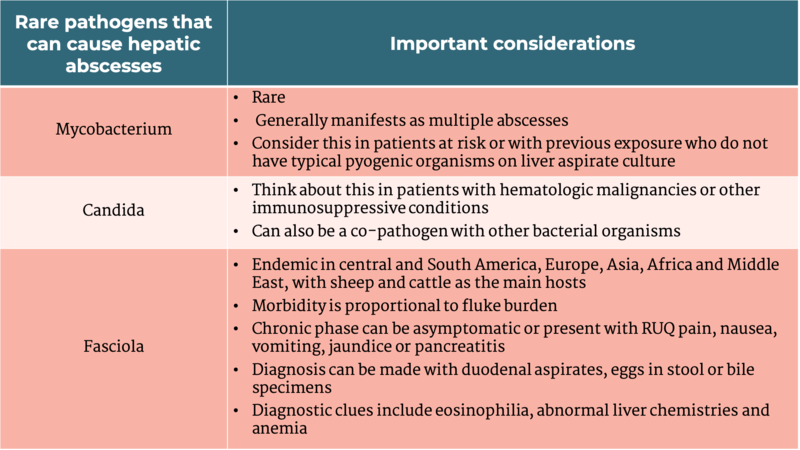

Table 3- Uncommon causes of hepatic abscesses

Adapted from: Davis J, McDonald M. Pyogenic liver abscess. UpToDate. Sep 2020. and Leder K, Weller P. Liver flukes:fascioliasis. UpToDate. Sept 2020