Food Security in the Adult with Liver Disease

Malnutrition Identification is Step One of Treatment

As explored and summarized in my earlier post on Malnutrition in the Adult with Cirrhosis, malnutrition is common in patients with cirrhosis and may manifest with frailty and/or sarcopenia which impact outcomes. Patients with liver disease may have undernutrition or malnutrition with obesity, both of which can cause muscle mass loss. Malnutrition impacts 50% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis and up to 70% of patients with advanced liver disease have resultant sarcopenia associated with higher rates of complications and lower rates of survival.

Optimal nutrition is a cornerstone of management for liver disease, specifically for those with metabolic (dysfunction)-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD, previously non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or NAFLD).

In my prior post we reviewed that consideration of malnutrition is paramount at visits, that patients should be connected with dietary resources and counseling for screening and treatment, and that objective screening tools can boost identification and treatment of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia. By individualizing dietary counseling, we can help patients boost their protein intake, eat a balanced diet, and decrease salt intake to minimize cirrhosis related complications.

However, patient preferences are only one piece of the larger treatment for malnutrition and exist in the larger societal context which may impede many patients’ ability to sustainably obtain their preferred and/or clinically desired nutritional intake. A “nutrition prescription” will only treat malnutrition if a patient has access to the prescribed plan. A key step in determining an appropriate nutrition prescription involves understanding the impact of food insecurity amongst our patient populations.

Food Insecurity - Defining the Problem

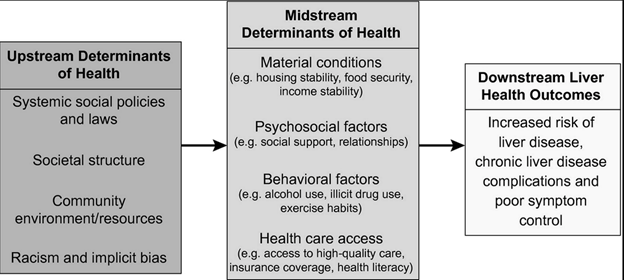

Food insecurity can be defined as having limited or uncertain access to nutritionally adequate food, limited by a lack of money and other resources. Food insecurity is common, impacting one in ten American households according to the USDA and over one in three low-income households. During the COVID-19 pandemic food insecurity has only increased. Food insecurity exists in the larger societal construct and a patient’s built environment, including what resources are accessible. Food insecurity is only one of many interacting social determinants of health impacting patients with liver disease, as outlined by Kardashian et al below

Figure 1: From Karshashian et al: Conceptual framework for the contribution of social determinants of health to health inequities, adapted to liver disease. Upstream determinants lead to differential exposures to midstream factors, which in turn engender differential vulnerabilities to downstream health outcomes and create health inequities.

Recently there has been a growing recognition of the need to assess nutritional insecurity, recognizing that while the term food insecurity technically incorporates access to nutritional food, more specifically targeting food meeting the nutritional criteria for a specific disease is also beneficial to patient well-being. This would apply to patients with liver disease as well, targeting nutritionally rich, specifically disease- relevant foods, including those with high protein or low salt, high in micronutrients that are often lacking in chronic liver disease.

The Impact of Food Insecurity in Development of Liver Disease

Multiple studies have demonstrated an independent association between food insecurity and liver disease. Tapper et al found in a cross-sectional analysis of over 3000 patients that food insecurity was associated with higher liver stiffness on transient elastography for adults over 50 years old. Tamargo et al showed food insecurity independently increased the risk for advanced liver fibrosis.

Populations from low-income neighborhoods are at risk for lower diet quality, including incorporation of high-fat, nutritionally deficient, more financially accessible options. Patients living in “food deserts,” or neighborhoods with low access to reliable food, are at risk for increased food insecurity with limited access to nutritious food options. There is concern that patients living in “foods swamps” or neighborhoods saturated with unhealthy food choices may be particularly at risk for targeting from unhealthy food and beverage marketing with higher rates of obesity.

Noureddin et al noted a higher incidence of NAFLD amongst those with a poor diet including processed meats, high cholesterol, and low fiber. Golovaty et al showed food insecurity may be independently associated with NAFLD and advanced fibrosis among low-income adults. Food insecurity is also associated with other metabolic diseases including diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.

The relationship between food insecurity and other causes of liver disease has not been as well studied. Food insecurity is prevalent amongst those with heavy alcohol use and is highly correlated with substance use. Food insecurity has been associated with increased adverse health behaviors, including heavy drinking, especially among young adults. As we are currently seeing a rise in young patients with alcohol related liver disease, this association may soon impact many patients under our care.

The Prevalence of Food Insecurity in Patients with Liver Disease

It is estimated that about one in four patients with MASLD are food insecure. Kardashian et al found that 28% of 4816 patients with NAFLD and 21% of 1654 patients with advanced fibrosis experienced food insecurity. These patients with food insecurity were more likely to be Black, Hispanic, foreign born, or live in poverty, which mirrors the National USDA reported disparities. Nearly one in three patients with NAFLD or significant fibrosis utilized emergency food assistance (from a church, food pantry, food bank or soup kitchen). Additional research is needed to understand food insecurity prevalence amongst patients with other types of chronic liver disease.

Patients with liver disease are asked to further restrict their potentially insecure diets with additional nutrition criteria. There is an association amongst households with food allergies reporting increased food insecurity, and with patients with chronic disease burden and food insecurity. While not necessarily as restrictive, the additional challenges to seek nutritionally correct food including high protein or low salt means we may not yet fully understand the burden of food and nutritional insecurity amongst patients with liver disease.

Impact of Food Insecurity in Patients with Liver Disease

When liver disease develops, food insecurity is associated with worse outcomes, though research in this area has been sparse. Kardashian et al found that among patients with NAFLD, those with food insecurity had higher all-cause mortality rates and increased healthcare utilization, even after controlling for other socioeconomic factors like poverty and education level. Data on disparities in long‐term prognosis and mortality among NAFLD populations are sparse and additional long-term research is needed. Data on long term impact of food insecurity among patients with other forms of liver disease is also lacking.

In other medical disciplines and research on other healthcare conditions with food insecurity, there has been a concern for compensatory changes in the context of food insecurity, leading to associated physiologic stress and metabolic changes. As Kardashian et al have applied this framework to liver disease, patients with food insecurity may have increased liver fibrosis progression with poor diet quality and higher rates of obesity and diabetes, higher rates of disruption of intestinal microbiota, and competing needs, leading to choices to spend money on food instead of healthcare, all increasing severity of disease and leading to worse outcomes.

Screening and Interventions for Food Insecurity in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease

Given the effect food insecurity may have on many of our patients, routine outpatient screening for food insecurity should be considered. The ‘Hunger Vital Sign’ is a quick screening tool incorporated into the Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services which can be utilized at outpatient visits. There is also a 6-item validated screening tool adapted from the full 18-item USDA U.S. Household Food Security Survey which is often used in research settings, which does include the two screening questions below as part of the more in-depth screening.

| Table 1: Two Question Food Insecurity Screener | |

| Question | Responses |

| Within the past 12 months, w worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more | a. Never true |

| b. Sometimes true | |

| c. Often true | |

| Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more | a. Never true |

| b. Sometimes true | |

| c. Often true | |

Table 1: The Hunger Vital Sign- 97% sensitivity and 93% specificity among US adults for food insecurity, answering “sometimes true” or “often true” for either question indicates a patient is either at risk for food insecurity or is food insecure.

Interventions for food insecurity must be targeted for the individual, but food insecurity is also a major public health crisis that will require greater societal level interventions. Patients who are screened with answers concerning for food insecurity should be given access to resources including referrals to case management, social work and/or nutritionists to improve their access to potential food assistance programs. Expansion of larger-scale assistance programs should be considered and in particular, more work is needed to ensure access to nutritionally appropriate foods for patients with chronic conditions. Hospital systems and hepatology programs/providers can consider collaborating with their local food access organizations that may be able to tailor meals to the needs for certain health conditions. One national resource is the Federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which can benefit those enrolled and has been shown to reduce food insecurity by about one-third for participants. However, patients must be aware of this resource and may need assistance navigating this program to gain access to their appropriate benefits, sometimes also facing eligibility barriers.

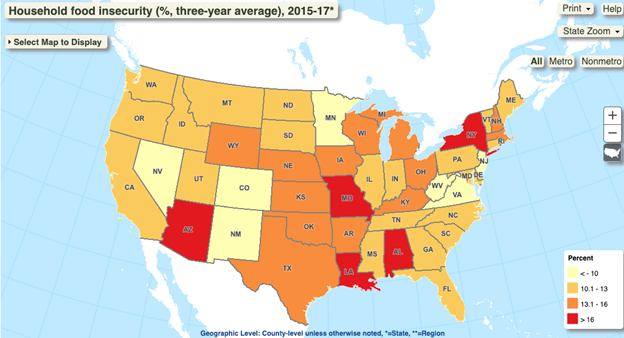

Step one is educating ourselves about the high levels of food insecurity amongst patients with liver disease. You can explore topics related to food insecurity via the USDA Food Atlas to learn more about risk in your area.

Figure 2: USDA Food Atlas of Household Food Insecurity (%, three year average 2015-2017)

Consider also listening to Dr. Kardashian’s recent LFN podcast on this topic for additional learning.

Teaching points

- Food insecurity is common across the US, and may limit success of nutritional interventions, often a crucial part of treatment in liver disease

- Patients with liver disease and food insecurity have worse outcomes

- Screen patients for food insecurity using the Hunger Vital Sign and connect them to resources to increase success of nutritional interventions