Management considerations and long-term outcomes in an aging population with biliary atresia

Background:

Biliary Atresia (BA) is the obstruction of bile flow due to progressive ascending destruction and obliteration of part or the entire extrahepatic biliary tree. It affects between one in 8,000 (Far East) to 16,000 (Europe, North America) live born infants. The clinical features of BA include jaundice, pale stools, and dark urine and manifest in the first few weeks of life. The diagnosis is made by an intraoperative cholangiogram (IOC), which is an invasive procedure. Therefore, decision of exploration and IOC in a neonate can be difficult and requires a combination of laboratory evaluation, imaging, and histology. Evaluation algorithms vary by center due to availability of certain modalities, expertise in neonatal liver pathology and interventional radiology.

Laboratory evaluation and ultrasound are performed in a majority of centers. Biochemical evaluation shows elevated direct or conjugated bilirubin, and frequently an elevated gamma glutamyl transferase level. There are several more recent studies describing newborn screening for biliary atresia, which in many East Asian countries is done using stool cards. The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines suggest that every newborn have a fractionated bilirubin level checked at birth, since many BA patients have elevations in their direct or conjugated bilirubin noted as early as 24-48 hours of life. In a recent large study evaluating the efficacy of implementation of a newborn screening program for BA, the age at which infants underwent Kasai portoenterostomy was significantly younger after screening was implemented.

The next steps in evaluation include imaging and invasive procedures. Ultrasound is often the first imaging modality used and may show the triangular cord sign, a radiographic finding representing the ductal remnant of the extrahepatic bile duct. In some instances, if findings on ultrasound suggest diagnosis of biliary atresia, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may be used as another non-invasive way to better assess the extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts. In addition, percutaneous transhepatic cholecystocholangiography is a minimally invasive procedure in which radio-opaque contrast is injected into the gallbladder under fluoroscopy to delineate the biliary tree, or lack thereof. Liver biopsy may be performed as part of the diagnostic work-up of biliary atresia if there is neonatal liver disease pathology expertise. Biopsy findings in these patients includes bile duct proliferation and fibrosis. Ultimately, these various modalities assist clinicians to decide to move forward with an IOC, which is the gold standard for diagnosis of biliary atresia.

Surgical treatment is via a Roux-en-Y hepatoportoenterostomy (HPE), also known as the Kasai procedure. This procedure entails the excision of the fibrotic biliary remnant, transection of the fibrous portal plate with dissection extending up to the bifurcation of the portal vein. The Roux-en-Y loop then reestablishes biliary-enteric continuity and allows bile drainage. Early diagnosis, timely surgical remediation, and surgical experience are crucial for best prognosis. However, many patients continue to develop progressive chronic liver disease, especially if the Kasai is done late in infancy, and therefore BA is currently the most common indication for liver transplantation in childhood.

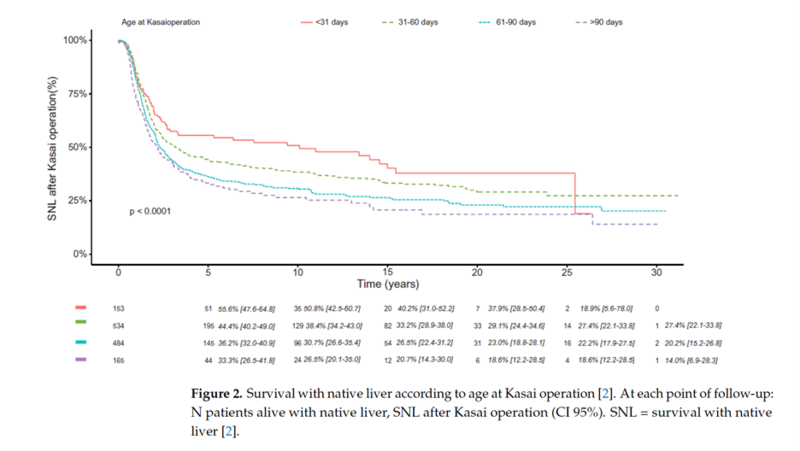

Rate of Survival with Native Liver in BA Patients:

In the largest and most recent European series, 5-year survival rate with native liver was 41%-55% and 35%-47% at 10 years after portoenterostomy. In a cohort study from France comprising 1340 post-PE patients, 20-year native liver survival remained unchanged at 26% between different eras during 1986–2015. However, the Japanese Biliary Atresia Registry reported a 20-year native liver survival rate of 49% among 3160 patients during 1989–2015. In both the French and Japanese national cohorts, early HPE (<30 days) showed 15-20% higher native liver survival at 15-20 years compared with those operated after age 60 days. This has led to many institutions implementing screening programs for early diagnosis of BA.

Kelly, D. (2023). J. Clin. Med.

Disease Progression in Adolescents and Adults:

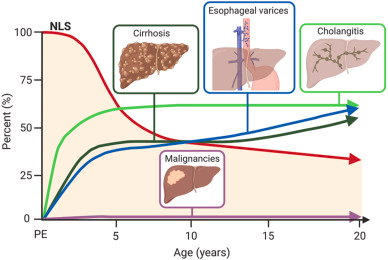

Individuals with BA surviving with their native livers post hepatoportoenterostomy are likely to develop complications in adolescence and early adulthood. The most common complications include cholangitis, portal hypertension, and variceal bleeding. Hepatocellular carcinoma is rare (~1%) in this cohort, which is much lower than in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis (~2-3%) and alcoholic cirrhosis (ranges from 3-9%).

Cholangitis is a frequent and serious complication after HPE. The frequency of cholangitis is highest during the first months and years after HPE, with a greater risk if clearance of bilirubin is not achieved. However, one third of native liver survivors still experience cholangitis in adulthood.

Portal hypertension, an increased pressure gradient between the portal venous system and the inferior vena cava or hepatic vein due to hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis, is a common complication post-HPE. Sequelae of portal hypertension include thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly, ascites, the formation of esophageal/gastric varices, hepatopulmonary syndrome, hepatorenal syndrome, chronic encephalopathy, and portopulmonary syndrome. Studies report that the presence of portal hypertension during adolescence has been shown to increase the risk of liver transplantation in adulthood by 7-fold. In select patients one may consider a portosystemic shunt to alleviate severe portal hypertension. However, due to hypoplastic intrahepatic portal veins and frequent small patient size, surgical shunts are less likely to be successful in BA patients but may sometimes help bridge the patient to liver transplantation.

Furthermore, trending biochemical markers may allow clinicians to prognosticate outcomes. Serum bilirubin levels above the upper limit of normal (>21 umol/L) at the age of 12 years predicts the need for liver transplantation in adulthood. In a report from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, adults demonstrated an increased risk of wait list mortality compared with adolescents (10.9 higher risk on multivariate analysis). Reports have also shown that adults with BA requiring liver transplantation provide a surgical challenge due to changes in their vascular system (enlargement of splenic artery, splenic artery aneurysms, etc.).

Fig. 1. Cumulative proportional occurrence of cirrhosis, esophageal varices, cholangitis and liver malignancies in relation native liver survival (NLS) from portoenterostomy (PE) to adulthood

Hukkinen M.. (2022). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol.

Long-Term Health Issues of BA with Native Livers:

In BA patients, both height and weight gain are impaired secondary to ongoing cholestasis and increased energy utilization. Thus, frequent surveillance of adequate nutritional status is essential. Once jaundice and bile flow are restored, growth impairments are amended. A French cohort with 63 patients who survived at least until 20 years of age with a native liver reported 78% of patients with adult height at or above the mean. Other health issues to consider this patient population is bone health. Vitamin D deficiency affects the majority of patients with HPE, and insufficiency may persist up to one year after a successful HPE despite enteral supplementation. Possible mechanisms of low vitamin D include depletion of intestinal bile acids and poor hepatic 25-hydroxylation. Low levels of vitamin D predispose these patients to rickets as well as osteoporosis even after a successful HPE. One study reported the incidence of bone fractures can be as high as 15% in native liver survivors who had normalized their bilirubin but were not on routine vitamin D supplementation. This risk of bone disease increases with development of cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease.

Lastly, in a large North American sample, health-related quality of life outcomes was significantly reduced among BA native liver survivors when compared to healthy children and like pediatric liver transplant recipients. Poor quality of life outcomes were secondary to increased hospital visits, stress, and adaptation to illness.

Summary:

Overall, advances in both medical and surgical care have significantly improved the prognosis of patients with BA. Nearly half of patients survive with their native liver for over 10 years. However, most are affected by complications including recurrent cholangitis and complications of portal hypertension, and therefore patients require life-long follow-up with a hepatologist. Native liver survivors are also predisposed to non-liver related complications like impaired growth, bone health, and reduced quality of life. Thus, further insight into long-term complications, transition of care, and development of accurate follow-up tools are needed to continue to improve care for native liver survivors throughout adulthood.