Palliative care and Advanced Liver Disease

Palliative Care (PC) is a multidisciplinaryapproach to medical care that improves the quality of life of patients and their caregivers by addressing their physical, spiritual, and psychosocial needs. The benefits of palliative care are being increasingly recognized for patients with decompensated cirrhosis. The AASLD developed a guidance statement in 2022, supporting early integration of PC for all patients with advanced liver disease and summarizing approaches to symptom-based management.

What are some Palliative Care needs for adults with advanced liver disease?

- High physical, mental, and spiritual symptom burden among patients

Table 1: Comparison of common symptom prevalence (range min to max) in end-stage liver disease and cancer

| Symptom | ESLD (%) | Cancer (%) |

| Pain | 30-79 | 30-97 |

| Breathlessness | 20-88 | 16-77 |

| Insomnia | 26-77 | 3-67 |

| Fatigue | 52-86 | 23-100 |

| Anorexia | 49 | 76-95 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 58 | 2-78 |

| Anxiety | 14-45 | 3-74 |

- Significant caregiver burden

- Limited advance care planning and communication about goals of care

- Burdensome end of life care

What is the role of Palliative Care?

- Increases patient satisfaction

- Treats people and not just disease

- Strengthens patient-family-provider relationships

- Helps to define a patient’s goals in the context of his/her evolving medical conditions

- Reduces health care costs as a product of the above

What does providing Palliative Care require?

- Knowledge of the disease state, prognosis, pharmacology

- Communication skills for assessment of patient’s beliefs/values, eliciting goals of care, coordination of care, active listening

- Skills in symptoms management (acute or chronic)

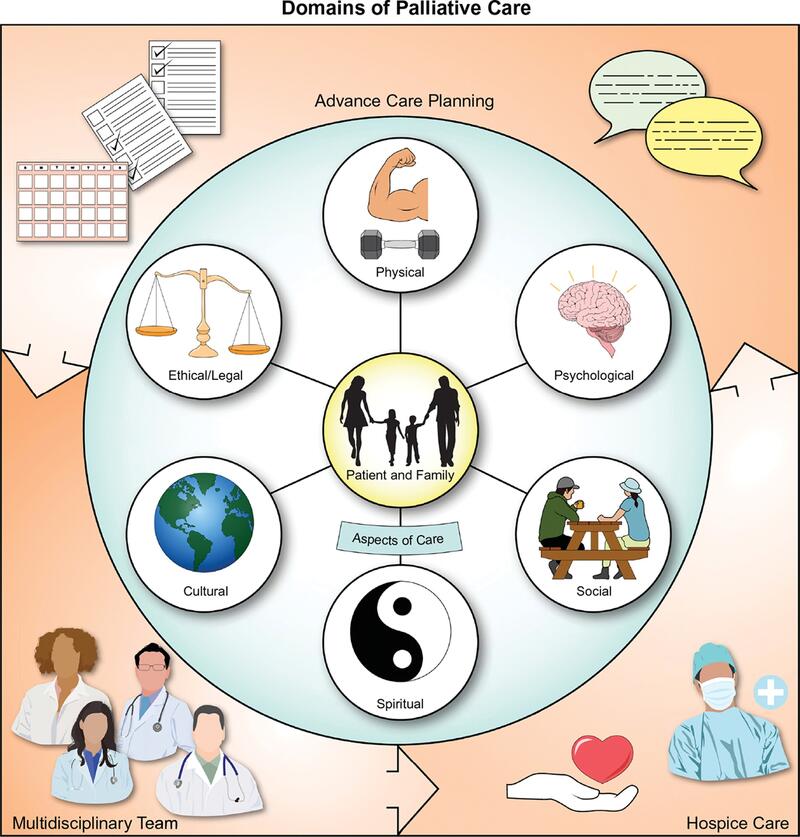

Figure 2) 8 domains of palliative care, as defined by the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care Guidelines, 4th Edition.

Domain 1) Structure and Process of Care: Focus on the interdisciplinary nature of PC, and commitment to continuity across care settings and high-quality care.

Domain 2) Physical Aspects of Care: Assessment should focus on relieving symptoms, maintaining quality of life and functional status.

Domain 3) Psychological and Psychiatric Aspects of Care: Psychological status needs to be assessment and managed, including that of family members. Caregivers of patients with cirrhosis report significant burdens including navigating access to health services, reductions in their own health and difficulty coping, mood disturbances, and financial burdens.

Domain 4) Social Aspects of Care: Assessment should address environmental and social factors (social support network, finances, access to care).

Domain 5) Spiritual, Religious, and Existential Aspects of Care: Care Team members must acknowledge their own spirituality. Offer support of a spiritual counselor.

Domain 6) Cultural Aspects of Care: Respect values, beliefs, and traditions related to health, illness, family caregiver roles and decision making.

Domain 7) Care of the Patient Nearing End of Life: Early access to hospice care should be facilitated when possible. Provide support and education to the family.

Domain 8) Ethical and Legal Aspects of Care: Address guardianship and goals of care. Communicate prognosis for informed decision making.

Primary vs Specialty Palliative Care

Primary PC can be delivered by any member of the hepatology care team. A feasibility trial of an outpatient primary palliative care intervention led by hepatology nurses with palliative care and communication training was acceptable to recently discharged patients and their health care teams, and associated with improved health-related quality of life.

In the case of Mrs. Adams (question stem above), the hepatologist can provide PC starting with hepatic encephalopathy management by adjusting lactulose. They can also address ascites management with adjusting diuretics, discussing sodium intake, and consideration of paracentesis. They can consider referral to PC specialist for comprehensive physical/mental/spiritual health assessments, additional support, and further complex symptom management if the hepatology clinic is unable to provide a full range of support that the patient needs.

Hospice is end of life care (≤6 months prognosis) focused on allowing people in their final phases of life to live as comfortably as possible. It focuses exclusively on comfort rather than disease-directed curative treatment.

Table 2: Similarities and differences between primary PC and specialty PC, and hospice. Adapted from AASLD 2022 guidance statement.

| Primary PC | Specialty PC | Hospice | |

| Primary Focus | Quality of life, symptoms, psychosocial and spiritual support | Quality of life, symptoms, psychosocial and spiritual support | Quality of life, symptoms, psychosocial and spiritual support |

| Delivered By | Primary or specialist treating teams | Palliative care clinicians/teams, as consultants or embedded within practices | Usually private hospice agencies (or within Veterans Administrations system for veterans) |

| Timing | Any time a need is identified | Any time a need is identified | Prognosis ≤6 months |

| Location | Anywhere under care of treating team | Inpatient, outpatient, community (home, nursing home) | Home, nursing home, inpatient (limited time for uncontrolled symptoms) |

| Reimbursement | Routine CMS billing | Routine CMS billing | Capitated payment model through Medicare Part A |

Barriers to PC in with patients with advanced liver disease:

- In the pre‐LT setting, there continue to be misconceptions that PC is synonymous with end‐of‐life care or hospice. For patients who were denied liver transplantation, a study showed that referral to PC providers was commonly delayed and often occurred very close to end of life, with a median survival of only 15 days in PC or hospice.

- Other provider barriers were highlighted in a recent qualitative study, namely, the unpredictable nature of the trajectory of liver disease, the lack of knowledge of the referral provcess, low skills/confidence to engage in prognosis discussions, and poor continuity of care.

- PC training is now a formal requirement in transplant hepatology training; however, only 40% of hepatology fellows report any exposure during training.

Future Directions

There is a need for more PC-specific education within the field of GI and hepatology. Those with chronic liver disease would benefit from earlier referral to PC. The AASLD online platform has highlighted several aspects of the guidance and incorporated additional input from experts in gastroenterology, transplant hepatology, nursing, oncology, and palliative care to create a “Palliative Care and Advanced Liver Disease” course (available on AASLD Liver Learning).

- The course includes 8 modules ranging from “Introduction to PC for Individuals with Decompensated Cirrhosis”, “Advanced Care Planning and Serious Illness”, to “Liver transplantation and Palliative Care”.

- Course modules are intended for a broad range of trainees and specialists, with some modules targeted towards specialist palliative care teams.

Although palliative care can be provided by specialists, all members of the hepatology care team should consider providing palliative care to address the symptomatic, spiritual, and psychosocial needs of their patients and their caregivers. Training in hepatology fellowship for providing PC may be feasible through the multiple educational initiatives including the AASLD Palliative Care and Advanced Liver Disease course, structured observations, multidisciplinary rounds, and an OSCE. Research questions remain about how feasibly can PC assessments and management models be integrated into transplant and non-transplant settings.