Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma

This edition of Pathology Pearls will focus on fibrolamellar carcinoma, a subtype of hepatocellular carcinoma which stands in contrast from all other HCCs with rather unique clinical, histopathologic, and molecular features.

Key Points:

Most notably, this specific tumor typically arises in younger patients in non-cirrhotic liver parenchyma, exhibits characteristic intratumoral lamellar fibrosis, and in virtually all cases is driven by a DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion.

Terminology & alternate names:

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC); fibrolamellar carcinoma (FLC); or hepatocellular carcinoma fibrolamellar type or variant.

Patient demographics & clinical features:

Fibrolamellar carcinoma characteristically affects younger patients (typically ages 10-35, median 22), without significant overrepresentation by sex but a suggestion of slight female preponderance. FL-HCC is most unusual among HCCs overall in that it arises in an absence of liver disease in a classically non-cirrhotic background. Presenting symptoms may be vague and can include abdominal pain or fullness, weight loss, & malaise, and occasionally presents with paraneoplastic syndrome.

Diagnosis:

Routine laboratory tests such as transaminases and alkaline phosphatase are typically non-elevated in FL-HCC. Regarding biomarkers, in contrast to conventional HCC, serum AFP is typically non-elevated, or if elevated is only modest, essentially never >200 ng/mL. FL-HCC is more likely to show serum elevations of an abnormal form of prothrombin called DCP (also known as PIVKA-II). On imaging, FL-HCC typically appears as a solitary mass, or less commonly multifocal, notably in a non-cirrhotic background. The tumor may show a central scar, which especially in the typical younger patient with no liver disease, can raise a radiographic differential of focal nodular hyperplasia. The tumor can grow quite large, sometimes exceeding 15 cm in size.

Gross pathology:

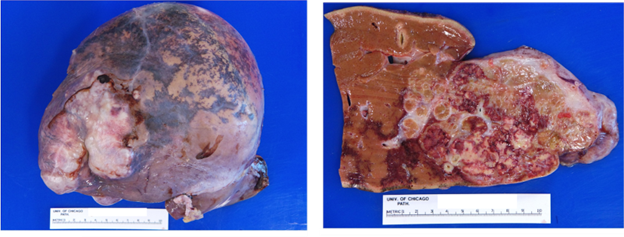

On gross examination of a resection or explant specimen, the tumor typically appears as a single large firm, well circumscribed, bulging tumor, which on cut sections may show visible fibrous bands and a central stellate scar. Bile staining, hemorrhage, and necrosis may be present. If the patient received neoadjuvant therapy such as transarterial radioembolization (TARE), some degree of necrotic treatment effect may be observed. The background liver should show unremarkable red-brown parenchyma with no nodularity (see figure 1, below).

Figure 1: Fibrolamellar carcinoma, gross pathology. Liver explant with a large 11 cm tumor, bulging at the liver capsule, which on cut sections shows approximately 30-40% necrosis attributable to TARE-based treatment effect. The background liver parenchyma is non-cirrhotic. Image credit: Tanner Storozuk MD.

Histopathology:

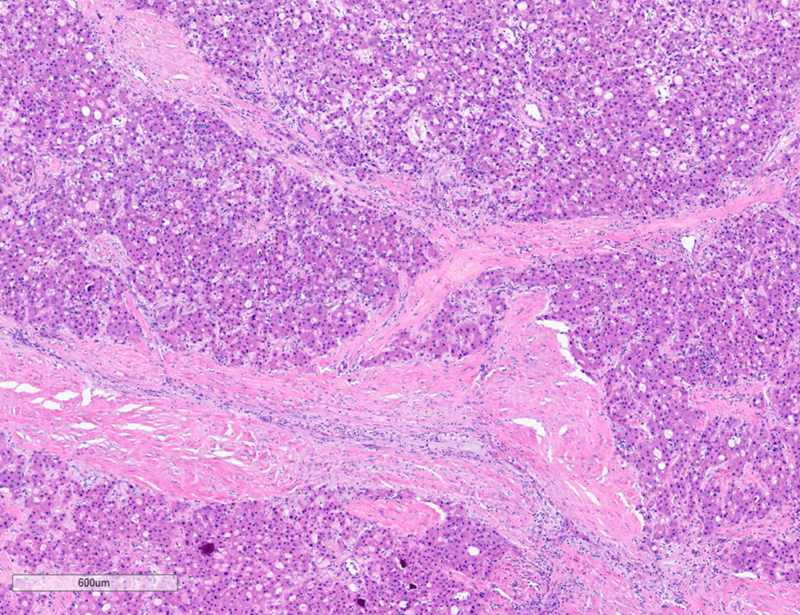

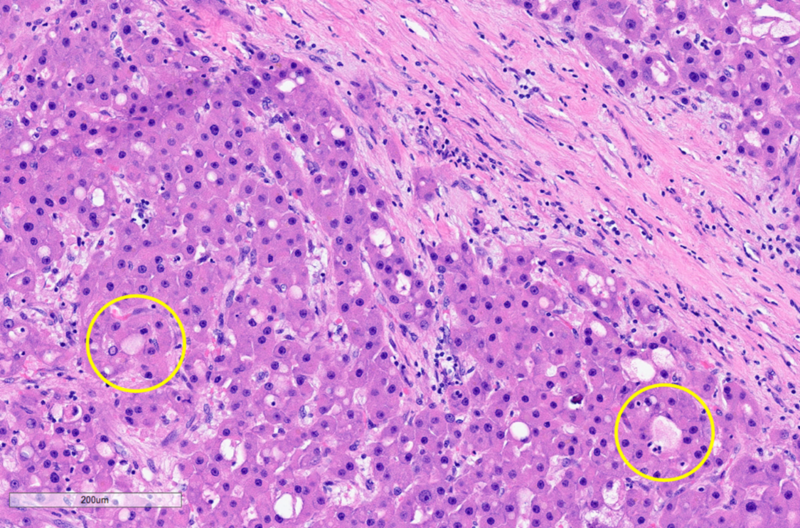

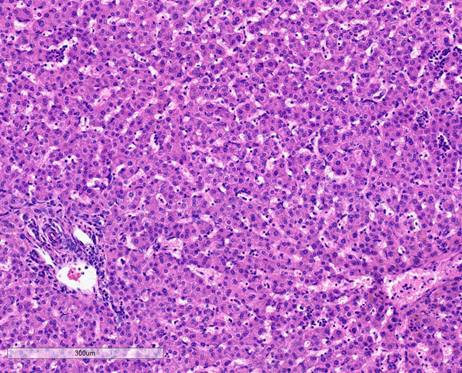

On microscopy, the tumor exhibits solid growth and is characterized by tumor cells arranged in cords and nests, strikingly separated by intervening intratumoral bands of fibrosis. These fibrous bands exhibit a parallel lamellar arrangement, which may be variable in distribution and prominence within the tumor (see Figure 2, below). The tumor derives its name from this striking intratumoral fibrosis pattern, though it is not required for the diagnosis, as it may be less distinct in some cases. The tumor cells are large and polygonal, with ample granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, well-defined cell borders, vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli. FL-HCCs may show intracytoplasmic inclusions, such as lightly-colored “pale bodies” composed of accumulated fibrinogen (see Figure 3, below), or “hyaline bodies” which are smaller & intensely eosinophilic. Some cases show modest bile production by tumor cells, similar to other HCCs. Some cases also show intratumoral cholestasis with secondary copper accumulation, comparable to some conventional HCCs. A minority of cases show pseudo-gland formation, which can be a pitfall for erroneously diagnosing combined HCC-cholangiocarcinoma. The background non-neoplastic liver parenchyma is characteristically unremarkable, with no cirrhosis (see Figure 4, below).

Figure 2: Fibrolamellar carcinoma, histopathology, low power. Solid tumor arranged in cords & nests, with striking prominent intratumoral lamellar fibrosis. Micrograph by Kevin Tanager MD.

Figure 3: Fibrolamellar carcinoma, histopathology, high power. Tumor cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm and intracytoplasmic “pale bodies” (examples in yellow circles), situated between bands of lamellar fibrosis. Micrograph by Kevin Tanager MD.

Figure 4: Background non-neoplastic hepatic parenchyma from case of fibrolamellar carcinoma, histopathology: The liver parenchyma is unremarkable, with preserved architecture with no evidence of fibrosis or cirrhosis, no significant portal inflammation, no bile duct injury or duct loss, and no steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, or necrosis. Micrograph by Kevin Tanager MD.

Special stains, immunohistochemistry, & FISH

As with conventional HCCs, the tumor shows reduction and loss of reticular meshwork by reticulin special stain. The tumor cells are immunoreactive for hepatocyte markers including Hep-Par1 and arginase-1, and may co-express CK7, as well as CD68 which highlights lysosomes & endosomes in the tumor cells. FISH may be utilized to detect the characteristic DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion (see below).

Molecular features:

The vast majority of FL-HCCs (>90%) harbor a microdeletion mutation on chromosome 19, resulting in a characteristic DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion. This fusion encodes a chimeric fusion protein prone to unregulated overexpression, triggering overactivation of protein kinase A (PKA), thus driving tumorigenesis. Rare alternate scenarios of FL-HCC occur due to biallelic mutations in PRKAR1A, an inhibitory subunit of PKA, generally in the setting of Carney complex but also rare sporadic cases.

Differential diagnosis:

As above, smaller FL-HCCs may appear similar to focal nodular hyperplasia on imaging, given their shared patient demographics and central scarring. Conventional HCC can be misdiagnosed as FL-HCC despite lack of classic FL-HCC features especially when swayed by clinical features when occurring in younger patients and/or in a non-cirrhotic background, though conventional HCC can occur in these settings. Morphologically, FL-HCC can appear similar to the “scirrhous”/”sclerosing” variant of HCC given that both FL-HCC and scirrhous HCC show intratumoral fibrosis, but scirrhous HCC arises in a cirrhotic background and lacks the molecular signature of FL-HCC. FL-HCC with prominent pseudo-glands may raise the possibility of combined HCC-cholangiocarcinoma. Neuroendocrine tumors with oncocytic morphology or paragangliomas may have similar cytomorphology to FL-HCC, but these will each have distinctly different immunophenotypic features and also lack the molecular signature of FL-HCC. Lastly, metastatic carcinomas from other sites with sclerotic stroma (such as some pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas or extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas) may resemble FL-HCC.

Treatment & Prognosis:

The prognosis of FL-HCC is overall better than conventional HCC; however, it is similar to the uncommon scenario of conventional HCCs arising in non-cirrhotic livers, relating to the improved status & treatment tolerance of patients without liver disease, with median survival of 6.7 years. FL-HCC more readily metastasizes to lymph nodes and peritoneum than conventional HCC. Some patients undergo neoadjuvant therapy including conventional chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or liver-directed ablative therapy such as transarterial radioembolization (TARE), in advance of resection, or as primary therapy in cases deemed unresectable. In cases deemed resectable (approximately 70% of patients), complete resection including hilar lymph node dissection is the most important prognostic factor, though recurrence is not uncommon even in cases of apparent complete resection (>50% of patients overall may recur), and some patients benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. A minority of patients undergo transplantation as their means of resection. The tumor is currently staged by the same parameters as conventional HCC, via the College of American Pathologists Protocol version 4.3.0.0 (2022).

References:

1. Ang CS, Kelley K, Choti MA et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival outcomes of patients with fibrolamellar carcinoma: data from the fibrolamellar carcinoma consortium. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2013;6(1):3-9.

2. Lefkowitch JH. Scheuer’s Liver Biopsy Interpretation. 10th ed. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier; 2020.

3. Torbenson MS. Biopsy Interpretation of the Liver.4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2022.