Antibiotics for SBP Prophylaxis – Why or Why Not?

Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in patients with cirrhosis have been widely adopted as a standard treatment approach since the early 1990s. Multiple gastroenterology and hepatology societies currently endorse them. Despite its longstanding acceptance, the supporting evidence for this preventive measure remains limited. Moreover, the broader consequences of routine prophylaxis—both for individual patients and public health—are increasingly concerning. Emerging data now point to the possibility that such preventive strategies may be detrimental. The medical community’s perspective on antibiotic prescription has evolved substantially over the last few years, with growing awareness of antimicrobial resistance. Given the evolving evidence and shifting clinical priorities, we aim to do a critical reappraisal of SBP prophylaxis in this Why Series article.

But first - why do ascites and SBP occur in patients with cirrhosis?

Ascites is the pathological accumulation of fluid within the peritoneal cavity. It is the most frequent initial decompensating event in cirrhosis, occurring in 5-10% of patients with compensated cirrhosis per year [1].

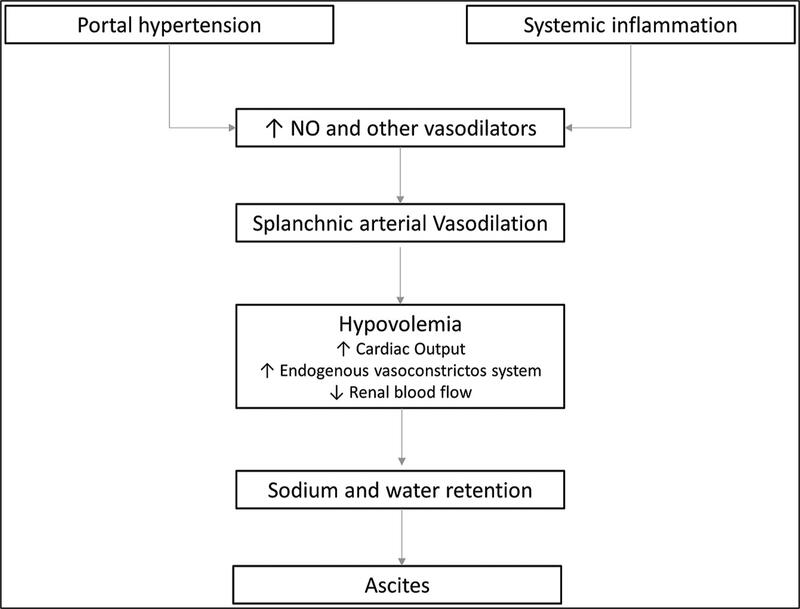

Ascites develops in patients with liver disease primarily due to portal hypertension and splanchnic vasodilation. Portal hypertension increases the pressure within the portal venous system, leading to the transudation of fluid into the peritoneal cavity. Splanchnic vasodilation, mediated by factors such as nitric oxide, results in a decrease in effective arterial blood volume, which triggers the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), leading to renal sodium and water retention, further contributing to fluid accumulation.

Figure 1: Pathophysiology of ascites in patients with cirrhosis

Tonon M, Piano S. Cirrhosis and Portal Hypertension: How Do We Deal with Ascites and Its Consequences. Med Clin North Am. 2023 May;107(3):505-516. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2022.12.004. Epub 2023 Feb 20. PMID: 37001950.

Table 1 lists the various types of infection of ascitic fluid, and their diagnostic criteria.

| Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP) |

Infection of the ascitic fluid without an identifiable intra-abdominal source of infection, with ascitic fluid PMN count ≥ 250 cells/mm3 |

Positive fluid culture with mono microbial growth |

| Culture-Negative Neutrocytic Ascites (CNNA) or culture negative SBP |

PMN count ≥ 250 cells/mm3 Treated like SBP |

Negative fluid culture |

| Monomicrobial bacterascites |

PMN<250 cells/mm3 |

Positive fluid culture (monomicrobial growth) |

| Polymicrobial bacterascites |

PMN<250 cells/mm3 Usually indicates needle perforation |

Positive fluid culture (polymicrobial growth) |

| Secondary peritonitis |

PMN>250 cells/mm3 Usually indicates intraperitoneal source of infection like diverticulitis |

Positive fluid culture (polymicrobial growth) |

Table 1: Variants of infection in ascitic fluid

PMN: polymorphonuclear leukocyte

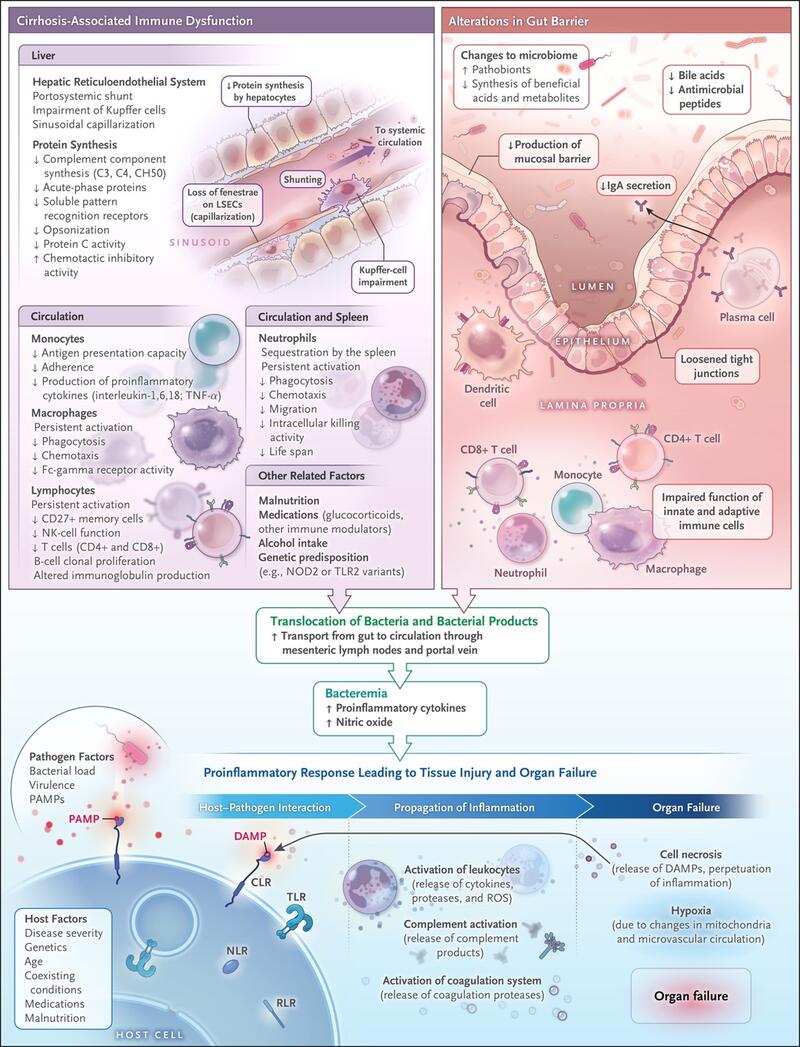

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is one form of infection of the ascitic fluid, that occurs in the absence of an evident intra-abdominal source of infection. It is most commonly seen in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. The pathogenesis of SBP involves bacterial translocation, which is the passage of bacteria from the gut to the bloodstream and other extraintestinal sites. This process is facilitated by increased intestinal permeability, bacterial overgrowth, and impaired host immune defences [2].

Figure 2: Role of Changes in the Gut–Liver Axis and Cirrhosis-Associated Immune Dysfunction in the Development of Infections.

Bajaj JS, Kamath PS, Reddy KR. The Evolving Challenge of Infections in Cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2021

Why are we concerned about SBP?

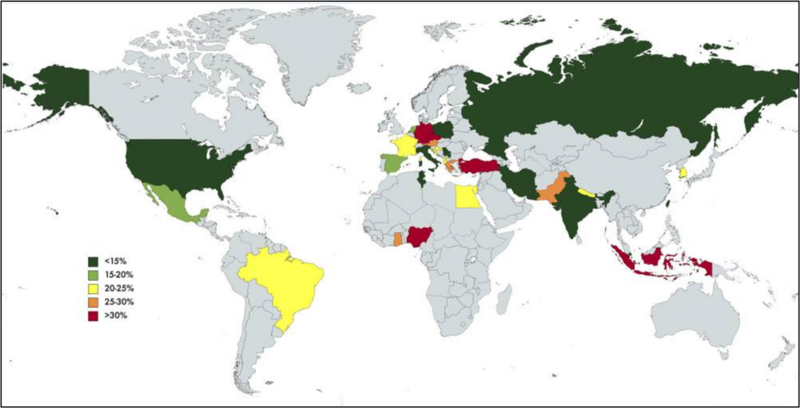

The 1-year probability of developing SBP in patients with cirrhosis and low ascitic fluid protein concentration can range between 20% and 60%, depending on the severity of liver and/or kidney dysfunction. According to a meta-analysis, the global pooled prevalence of SBP among patients with cirrhosis is approximately 17%, with significant geographical variations, as shown in Figure 2. The incidence of SBP in asymptomatic cirrhotic patients undergoing routine outpatient paracentesis is reported to be around 2%.

Figure 2: Global prevalence of SBP

Tay PWL, Xiao J, Tan DJH, Ng C, Lye YN, Lim WH, Teo VXY, Heng RRY, Yeow MWX, Lum LHW, Tan EXX, Kew GS, Lee GH, Muthiah MD. An Epidemiological Meta-Analysis on the Worldwide Prevalence, Resistance, and Outcomes of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in Cirrhosis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Aug 5;8:693652. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.693652. PMID: 34422858; PMCID: PMC8375592.

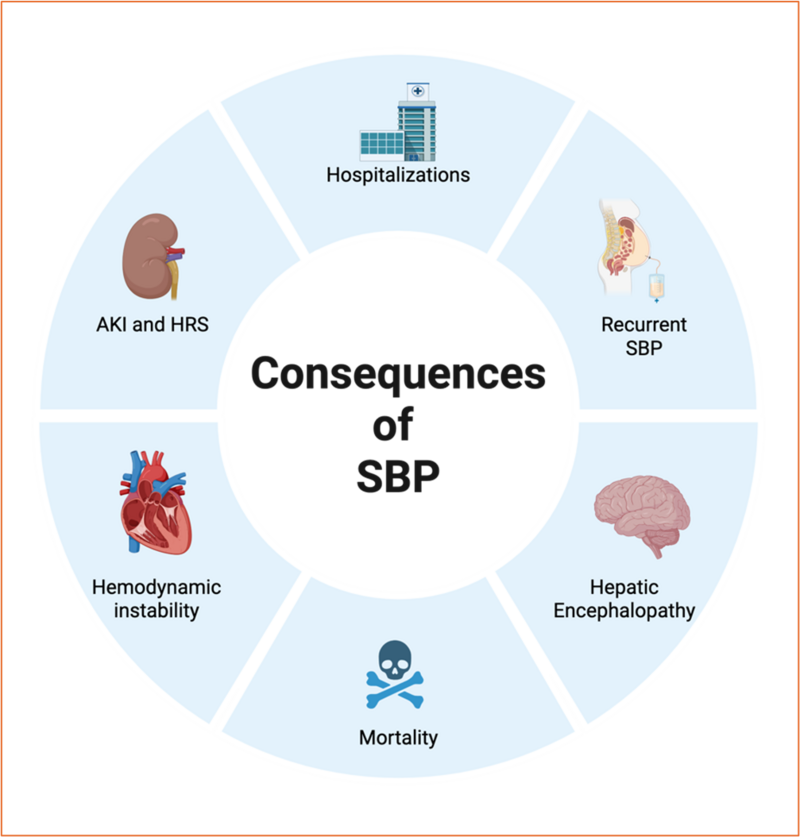

SBP leads to significant morbidity and mortality. The consequences of SBP include:

1. Acute Kidney Injury (AKI): SBP is frequently associated with AKI, with incidences of stage 1, 2, and 3 AKI being 27%, 16%, and 23%, respectively. The development of AKI significantly worsens the prognosis and increases mortality [6].

2. Hepatorenal Syndrome (HRS): SBP can precipitate HRS, a type of renal failure unique to patients with advanced liver disease. This condition is characterized by rapid deterioration in renal function and is associated with poor outcomes.

3. Mortality: In-hospital mortality for SBP is approximately 36%, and 12-month mortality is 68%. Long-term survival rates are also poor, with 32-month survival being only 24%.

4. Recurrent SBP: The cumulative incidence of recurrent SBP is around 10%, which further complicates the clinical course and management of these patients.

5. Hepatic Encephalopathy: SBP can exacerbate hepatic encephalopathy, leading to altered mental status and further complicating the clinical picture.

6. Hemodynamic Derangements: SBP can cause significant systemic, renal, and hepatic hemodynamic changes, including increased peripheral vascular resistance, reduced cardiac output, and aggravated portal hypertension. These changes contribute to the rapid progression of renal and hepatic failure.

7. Hospitalization and Healthcare Costs: Patients with SBP have higher hospitalization rates, longer lengths of stay, and increased healthcare costs compared to those without SBP.

Figure 4: Consequences of SBP (created on BioRender)

What are the risk factors for SBP?

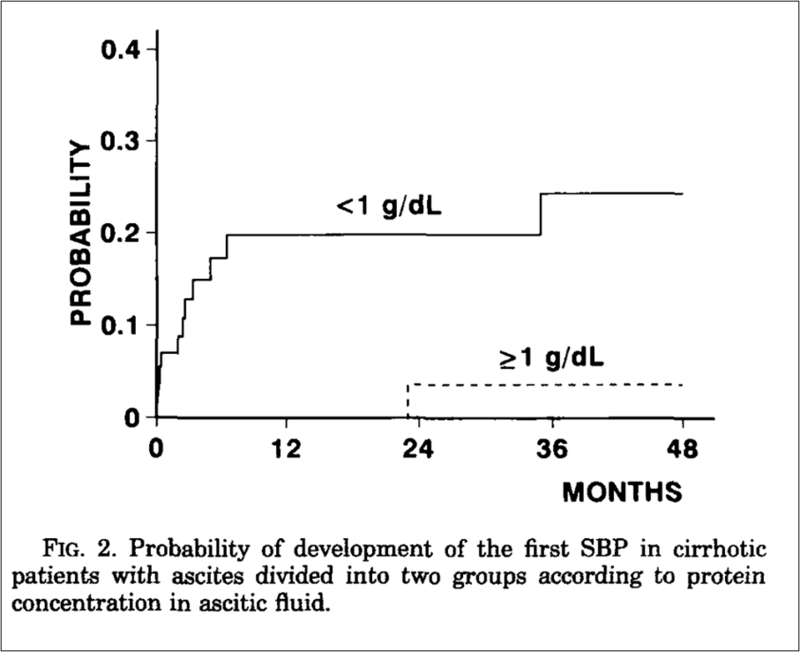

Risk factors for SBP in patients with cirrhosis include several clinical and laboratory parameters. The AASLD highlights that patients with cirrhosis and acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage are at high risk for infections including bacteremia and SBP. Traditionally, low ascitic fluid protein concentration was thought to predispose to SBP due to decreased ascitic complement levels and opsonic activities. As shown in the graph below from a study published in 1992, patients with ascitic fluid protein <1g/dL had higher probability of developing SBP.

Other significant risk factors identified in the literature include advanced age, refractory ascites, renal failure, low serum sodium levels, elevated bilirubin levels, and Child-Pugh class C.Patients with a previous episode of SBP are also at increased risk for recurrence.

Figure 3: Probability of development of first episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with ascites, divided into two groups, according to ascitic fluid protein content

Llach, J., et al., Incidence and predictive factors of first episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis with ascites: relevance of ascitic fluid protein concentration. Hepatology, 1992. 16(3): p. 724-7

Who needs SBP prophylaxis?

Primary prophylaxis and secondary prophylaxis for SBP in patients with cirrhosis differ in their indications and patient populations. Primary prophylaxis is aimed at preventing the first episode of SBP in high-risk patients who have not yet experienced an episode. Secondary prophylaxis is intended to prevent recurrence in patients who have already had an episode of SBP. Table 2 shows the current AASLD recommendations for SBP prophylaxis.

| Primary prophylaxis | Patients with cirrhosis and upper GI bleeding | Ceftriaxone 1 g IV q24h up to 7 days |

|

Patients with advanced cirrhosis (Child-Pugh score ≥9 and serum Bi ≥3 mg/dL) and low ascitic fluid protein (<1.5 g/dL) with either impaired renal function (Cr ≥1.2 mg/dL or BUN ≥ 25 mg/dL) or hyponatremia (Na < 130 mmol/L) |

Norfloxacin 400 mg daily or Ciprofloxacin 500 mg daily or Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 1 double-strength tablet daily, until liver transplantation or death | |

| Secondary prophylaxis | Cirrhosis and first episode of SBP | Norfloxacin 400 mg daily or Ciprofloxacin 500 mg daily or Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 1 double-strength tablet daily, until liver transplantation or death |

Table 2: Current guideline recommendations for SBP prophylaxis

Bi: bilirubin; Cr: Creatinine; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen

So, what is the evidence for SBP prophylaxis? Let us critically review the literature!

Evidence for SBP prophylaxis in GI bleeding

Prompt antibiotic initiation is the standard of care in acute variceal bleeding. Several trials have investigated various antibiotic prophylactic regimens in this scenario. Most notable, is the RCT by Fernández et al., comparing ceftriaxone to norfloxacin in patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal hemorrhage (Figure 4). The end point of the trial was prevention of bacterial infection within 10 days of inclusion. The authors concluded that that ceftriaxone was more effective in preventing SBP or bacteremia compared to norfloxacin (11% vs. 33%, p = 0.003).

Figure 5: Probability of remaining free of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or bacteremia in patients receiving ceftriaxone (continuous line) and norflaxacin (dotted line) in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Fernández J, Ruiz del Arbol L, Gómez C, Durandez R, Serradilla R, Guarner C, Planas R, Arroyo V, Navasa M. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006 Oct;131(4):1049-56; quiz 1285. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.010. PMID: 17030175.

In a meta-analysis of 5 trials published in 1999 and cited in the guidelines, it was found that intestinal decontamination with antibiotics (mostly oral norfloxacin) reduced the rates of infections, including SBP, and improved short-term mortality. The analysis included 534 patients with a mean follow up period of 12 days.

In a more recent Cochrane review from 2010, pooled data showed that prophylactic antibiotic use significantly reduced mortality from bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis and upper GI bleeding. However, on stratifying by antibiotic, the effect seemed to have diluted, as no beneficial effects on mortality was observed.

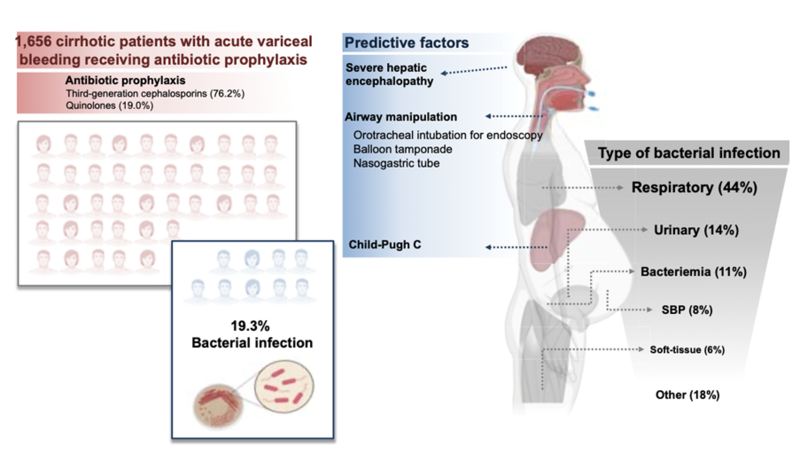

Although the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in acute variceal hemorrhage has traditionally been justified by its potential to limit gut-derived bacterial translocation and thereby prevent SBP, emerging evidence challenges this rationale. A recent multicenter cohort study involving patients with acute variceal bleeding demonstrated that lower respiratory tract infections were the predominant infectious complication in these patients – conditions in which bacterial translocation from the gut likely play a minimal role. Despite prophylactic antibiotic use, around 20% of these patients still developed bacterial infections (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Bacterial infections in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage in the era of antibiotic prophylaxis

Martínez J, Hernández-Gea V, Rodríguez-de-Santiago E, et al. Bacterial infections in patients with acute variceal bleeding in the era of antibiotic prophylaxis. J Hepatol. 2021;75(2):342-350. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2021.03.026

The trials in the meta-analysis that currently underpins the guideline recommendations are old, with the most recent one conducted in 2006, preceding significant advancements in endoscopic techniques.

It is conceivable that antibiotic prophylaxis may be selectively indicated for patients with severe liver disease only. However, given that current guidelines recommend prophylaxis for all patients with cirrhosis and GI bleeding, conducting a trial that would limit prophylaxis only the severely ill would present ethical constraints.

Evidence for secondary prophylaxis

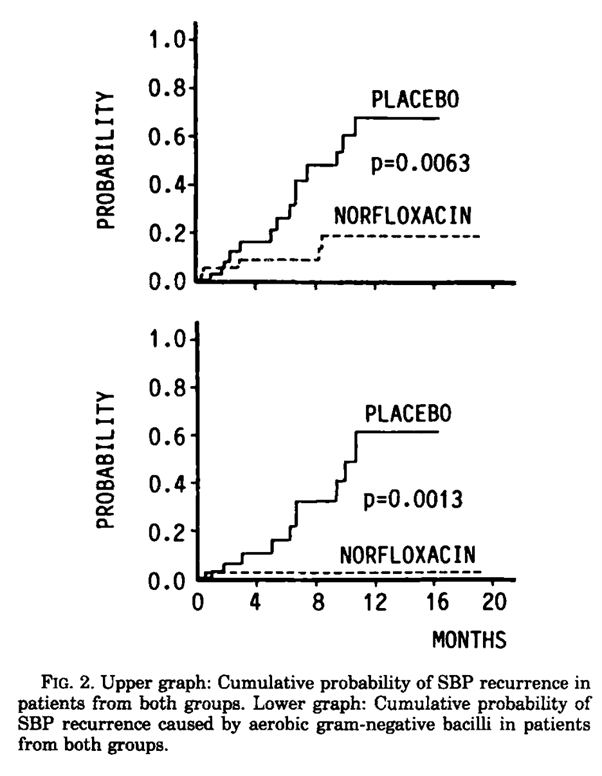

When it comes to antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with history of SBP, evidence is not robust. Patients with a prior episode of SBP are at a very high risk of SBP recurrence. Hence, secondary prophylaxis after an initial episode of SBP is widely incorporated into standard clinical practice. This is based on a single RCT published in 1990, in which 80 patients were randomized either to receive norflaxacin or placebo, for one year. The study demonstrated a substantial reduction in the recurrence of SBP, from 68% in the placebo group to 20% in the norfloxacin group.

Figure 7: Norfloxacin reduces the probability of SBP by aerobic gram negative bacilli compared to placebo

Ginés P, Rimola A, Planas R, et al. Norfloxacin prevents spontaneous bacterial peritonitis recurrence in cirrhosis: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology. 1990;12(4 Pt 1):716-724. doi:10.1002/hep.1840120416

However, when we look closer, the protective effect was specific to SBP episodes caused by aerobic gram-negative bacilli, with no observed benefit in preventing SBP due to other pathogens, culture negative infections, or those involving multidrug-resistant organisms (Figure 7). Additionally, norfloxacin did not reduce overall mortality, the total number of infections, or other cirrhosis-related complications during the study period.

Despite the absence of subsequent placebo-controlled trials over the past 35 years, the findings of this early study have been broadly adopted into clinical practice, effectively solidifying secondary prophylaxis as the standard of care.

On the contrary, numerous studies have evaluated SBP primary prophylaxis across diverse patient populations and antibiotic agents. A 2020 Cochrane review evaluated both the efficacy and potential harms of antibiotic strategies for SBP prevention, including more than 20 RCTs. Among close to 3900 participants from high-quality trials, no mortality benefit was found with antibiotic prophylaxis, whether it was used as a primary or secondary strategy. The authors emphasized the persistent uncertainty surrounding the overall benefit of SBP prophylaxis, as well as which, if any, antibiotic regimen might be superior. The strength of evidence was rated as very low due to several methodological limitations across the included studies, including small sample sizes, high risk of bias, and heterogeneity in reported outcomes.

Evidence for primary prophylaxis

The use of primary antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent an initial episode of SBP in patients with ascites remains a less clearly defined practice. Early studies conducted between 1986 and 1993 suggested that low ascitic fluid protein concentrations increased susceptibility to SBP, likely due to impaired opsonic activity. However, subsequent evidence has cast a doubt on the reliability of low ascitic protein as an independent risk factor. Two large post hoc analysis found no significant association between low-protein ascites and increased SBP incidence, suggesting that the observed relationship in earlier studies may have been confounded by overall disease severity or other variables.

Clinical guidelines also reflect this uncertainty. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) supports prophylaxis based on an ascitic fluid protein threshold, whereas the AASLD limits it recommendation to individuals with advanced hepatic decompensation or renal dysfunction (Table 2).

| Society | Primary prophylaxis guideline |

|

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, European Association for the Study of the Liver |

Ascitic protein <1.5 g/dL |

| American Association for the Study of Liver Disease |

Ascitic protein <1.5 g/dL AND Advanced liver failure (Child Pugh>9 and Bi ≥3 mg/dL) OR Renal dysfunction (Cr>1.2, urea>25 mg/dL, or Na<130) |

| British Society of Gastroenterology | No recommendation |

Table 2: Primary prophylaxis recommendations from global societies

SBP Prophylaxis may not have much benefit. But is there any harm with SBP prophylaxis?

While spontaneous bacterial peritonitis prophylaxis (SBPPr) has long been viewed as a protective strategy in cirrhosis, emerging data reveal a spectrum of unintended harms. These concerns span antimicrobial resistance, adverse drug effects, microbiome disruption, and questionable clinical efficacy.

Antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP, especially when administered over long durations, could be a contributor to antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—a public health crisis responsible for millions of resistant infections annually. Patients with cirrhosis, who already face immune system impairments, are particularly vulnerable. Resistant infections now affect over a third of patients with cirrhosis worldwide. SBP prophylaxis using fluoroquinolones (FQs) has been directly linked to the development of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO), including carbapenem-resistant bacteria. When SBP occurs despite prophylaxis, the resulting infections are often resistant and associated with poorer outcomes, challenging the presumed protective benefit of lifelong antibiotic use.

Large observational analyses within the Veterans Health Administration have further highlighted the potential harms of SBPPr. One study involving over 7,000 patients with cirrhosis showed that those who received primary prophylaxis were more than twice as likely to experience their first SBP episode caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant organisms. Additionally, these patients had longer hospital stays compared to those who did not receive prophylaxis.

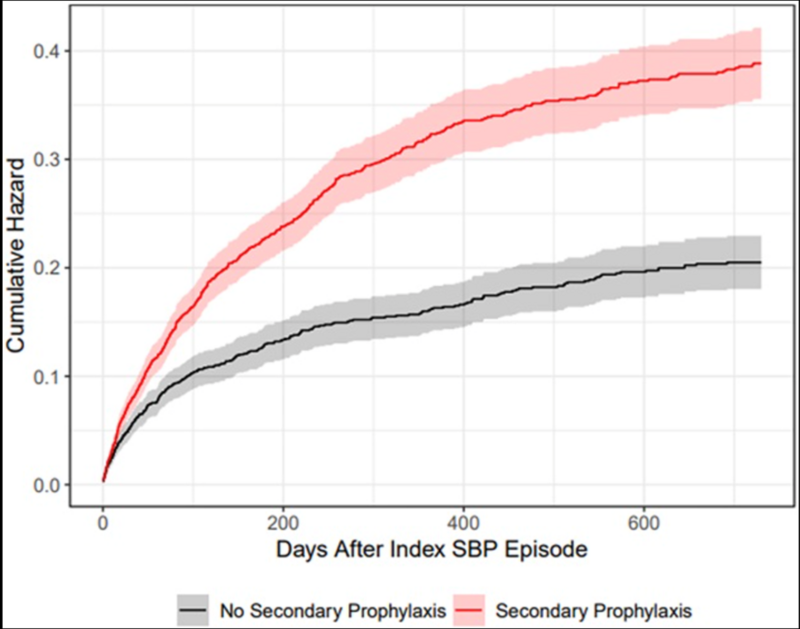

Another multi-database study revealed that patients on secondary SBP prophylaxis had a 60% higher risk of recurrence, undermining the foundational belief that prophylaxis prevents repeat infections. These findings suggest that prophylaxis may paradoxically worsen outcomes by fostering resistance and altering microbial dynamics.

Figure 6: Cumulative incidences of SBP recurrence in Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse. Data are presented as cumulative hazards for SBP recurrence with solid curves and 95% CI shading. Patients on secondary prophylaxis (red) had an unadjusted hazard ratio of 1.82 (95% CI: (1.59–2.10), P < 0.001) for SBP recurrence vs those who were not on secondary prophylaxis (gray).

Silvey S, Patel NR, Tsai SY, Nadeem M, Sterling RK, Markley JD, French E, O'Leary JG, Bajaj JS. Higher Rate of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Recurrence With Secondary Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Prophylaxis Compared With No Prophylaxis in 2 National Cirrhosis Cohorts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024

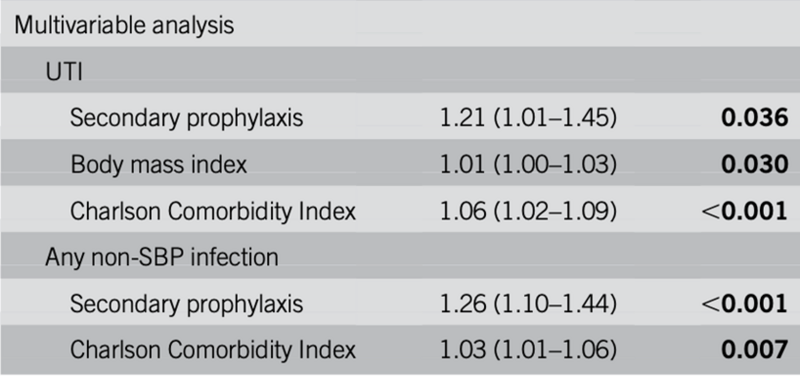

A study hot off the press, reported that use of Secondary SBPPr in two diverse cohorts, was associated with a higher risk of non-SBP infections, especially urinary tract infections (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Increased risk of UTI in patients on secondary prophylaxis for SBP

Silvey S, Patel N, O'Leary JG, et al. Secondary Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Prophylaxis Is Associated With a Higher Rate of Infections other than Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in 2 US-Based National Cirrhosis Cohorts. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. Published online March 10, 2025. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000837

Beyond resistance, antibiotic prophylaxis is associated with a host of adverse drug reactions. Fluoroquinolones—the mainstay of SBPPr—carry black box warnings due to risks such as tendon rupture, neuropsychiatric disturbances, hypoglycemia, and even aortic aneurysm complications. Norflaxacin, with poor oral bioavailability and high gut intraluminal concentrations, was discontinued in the U.S. by the manufacturer in 2015. FQs also significantly increase the likelihood of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), a potentially lethal complication, particularly in patients with cirrhosis. Although alternative agents like trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole may reduce the risk of CDI, they introduce other concerns, including hyperkalemia, blood cell dyscrasias and need for caution in renal dysfunction. These safety issues challenge the acceptability of lifelong prophylactic regimens, especially in vulnerable liver disease populations.

Long-term antibiotic exposure in cirrhosis can also impair gut health by disrupting the microbial ecosystem. The gut microbiota plays a critical role in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and immune function. In cirrhosis, microbial composition is already altered, and antibiotic use exacerbates this imbalance by promoting the growth of pathogenic species and suppressing beneficial ones. Furthermore, non-bacterial components of the gut ecosystem—such as fungi and phages—are also negatively affected by SBPPr. These disruptions can increase intestinal permeability, microbial translocation, and paradoxically heighten the risk of SBP and other infectious complications over time.

Conclusion

A uniform, one-size-fits-all approach to SBPPr is no longer justifiable in light of evolving evidence and rising concerns. While antibiotic prophylaxis during gastrointestinal bleeding may be beneficial in patients with advanced cirrhosis and UGIB, its routine use outside this setting requires re-evaluation. Particularly for secondary prophylaxis, clinicians should weigh individual patient risk factors against the growing burden of antimicrobial resistance, adverse drug effects, and uncertain mortality benefit. A nuanced, patient-centered strategy, grounded in antimicrobial stewardship and evolving data, is critical for optimizing care in patients with cirrhosis, as we await the results of trials like the ASEPTIC trial, evaluating the use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as primary prophylaxis for SBP.

Key Points

- Evidence for SBP prophylaxis is weak and outdated: The original trial supporting secondary prophylaxis had a small sample size and did not show a mortality benefit. Subsequent studies have been limited and inconsistent.

- SBP prophylaxis may promote antimicrobial resistance: Lifelong antibiotic use, particularly with fluoroquinolones, increases the risk of colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms and may lead to more severe infections when SBP occurs.

- Significant adverse effects are associated with prophylactic antibiotics: Fluoroquinolones carry FDA black box warnings and are linked to Clostridioides difficile infections, which are particularly dangerous in patients with cirrhosis.

- Gut microbiota disruption may paradoxically increase SBP risk: Long-term antibiotic exposure alters gut microbial balance, weakening mucosal defences and potentially facilitating translocation of pathogens.

- Guidelines should be revisited with a case-by-case approach: While prophylaxis during GI bleeding remains standard for patients with advanced cirrhosis, primary and secondary SBP prophylaxis should be individualized, prioritizing antimicrobial stewardship and patient safety.