Why do we care about aging in liver disease?

The aging global population is increasing with a projected increase of 22% (1.5 billion people) by 2050. The rise in steatotic liver disease (SLD), driven by metabolic-dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), has co-occurred with the aging global population. Estimates project an increase of people with MASLD from 33.7% to 41.4% (121.9 million people) in the United States by 2050. This corresponds with a projected increase in metabolic-dysfunction associated steatohepatitis (MASH) cirrhosis of 91.1% (1.15 million in 2020 to 2.2 million in 2050). Hepatologists will therefore see an increasing number of older adults with cirrhosis in the years to come. Older adults have increasing rates of co-morbidities, dementia, and frailty, which can affect cirrhosis-related management among older adults. This post aims to summarize the pathophysiological changes that occur in the aging body and the management considerations for older adults with cirrhosis.

Why does the liver change with age?

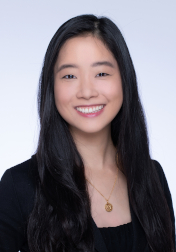

Aging leads to an increase in oxidative stress, an inflammatory response, and cellular senescence, ultimately resulting in progressive organ dysfunction. These hallmark changes affect the liver, leading to an increased risk of fibrosis and ultimately cirrhosis.

Figure 1. Liver Disease Pathophysiology with Aging from Stahl 2018. Macrophages in the Aging Liver and Age-Related Liver Disease.

Changes in Liver Characteristics

With increasing age, liver volume decreases by 20-40% with age. Blood flow through the liver also decreases with age. Moon et al evaluated portal vein age-related hemodynamic changes by comparing 4D flow MRI data of the main portal vein in healthy adults 30-39 years old, 40-49 years old, 50-59 years old, and 60-69 years old. They found that portal vein net flow decreased by about 40% in adults 60-69 years old compared to younger adults with a peak in hemodynamic parameters at around 45 years old. These changes ultimately lead to a reduction in functional liver cell mass.

Cellular Changes within the Liver

Aging leads to an increase in oxidative stress and development of cellular senescence, whereby cells enter a state of growth arrest while remaining metabolically active. These changes are due to multiple cellular alterations that occur with aging, including the reduction in cellular components critical in response to oxidative damage and the deposition of cellular components that lead to increased oxidative stress and inflammation. Table 1 describes specific liver-related cellular alterations that lead to increased oxidative stress with age. This combination of increased inflammation, reduced regenerative capacity, and cellular senescence lead to increased liver fibrosis and increased vulnerability to injury such as alcohol, drugs, and toxins.

Table 1. Pathophysiology of oxidative stress in liver

| Change in Liver | Results |

| Decrease in mitochondria and mitochondrial function |

|

| Protein denaturation in liver cells |

|

| Increase in ferroptosis, a pathway of iron-dependent cell death |

|

| Decrease in smooth muscle endoplasmic reticulum function |

|

| Shortening of telomeres, activating DNA damage response pathway |

|

| Decrease in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells function |

|

| Increased cellular senescence |

|

| Increased necroptosis, a process of programmed cellular death that promotes inflammation and immune responses commonly seen in viral infections, increases with aging in animal studies |

|

Changes in liver function tests

The aging liver is associated with changes in normal liver function tests. In particular, while AST and ALT remain normal, bilirubin, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and alkaline phosphatase increase with age. While bilirubin levels may decrease with reduced red blood cell turnover with age, reduced processing and elimination of bilirubin in the aging liver can lead to an increase in bilirubin levels. Some data suggest that bilirubin may be protective against oxidative stress, while others suggest no causality between total bilirubin levels and inflammatory markers. With increased oxidative stress and damage to cells, levels of GGT, a biomarker of glutathione depletion, may also increase. Alkaline phosphatase increases particularly due to a change in bone metabolism with aging. These changes are more pronounced in women possibly due to the effects of hormonal changes in bone metabolism with aging. Finally, different medications may lead to changes in liver function tests.

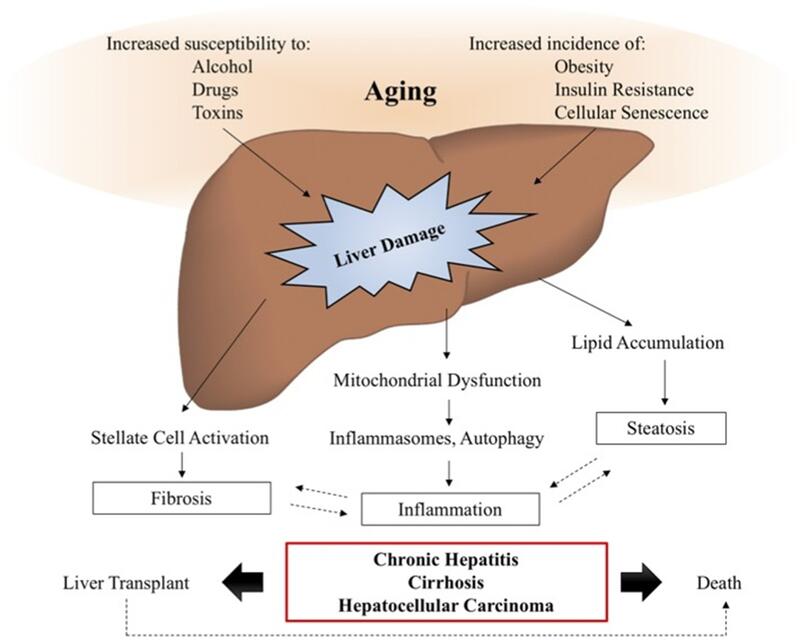

What type of liver disease do older adults get?

Figure 1.Liver disease among older adults from Old age as a risk factor for liver diseases: Modern therapeutic approaches Georgieva Experimental Gerontology.

Older adults have aging-specific risk factors that lead to an increased rate of liver disease. In particular, aging is associated with increased abdominal obesity and visceral fat that lead to an increased prevalence of MASLD and MASH in older adults. Older adults also have an increased risk of alcohol use disorder due to an increase in social isolation, divorce or bereavement, and increased rates of depression, reduced alcohol metabolism, and increased alcohol toxicity that lead to an increased risk of alcohol-associated liver disease and a worse prognosis with alcohol-associated liver disease among older adults. The clinical presentation of viral hepatitis is also more severe among older adults: Complications of hepatitis A including acute liver failure, pancreatitis, and prolonged cholestasis occur more commonly in older adults; rates of progression of chronic hepatitis B occur more commonly in older adults; hepatitis C transmission among older adults ≥ 65 years old may be due to surgery or blood transfusion before 1990; and older adults experience an accelerated progression of chronic hepatitis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) caused by hepatitis B and C. Age is also a risk factor for HCC, the 5th most prevalent cancer and the 3rd most important cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Additionally, about 20% of adults with AIH develop AIH at ≥60 years old and compared to younger adults tend to be less symptomatic and present with higher degrees of fibrosis and rates of cirrhosis. Other etiologies such as cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in the setting of cardiac dysfunction can occur more commonly in older adults.

What should we do to manage older adults with cirrhosis?

The management of older adults with cirrhosis should take into consideration aging-related comorbidities and disease states including increased frailty, polypharmacy, and dementia.

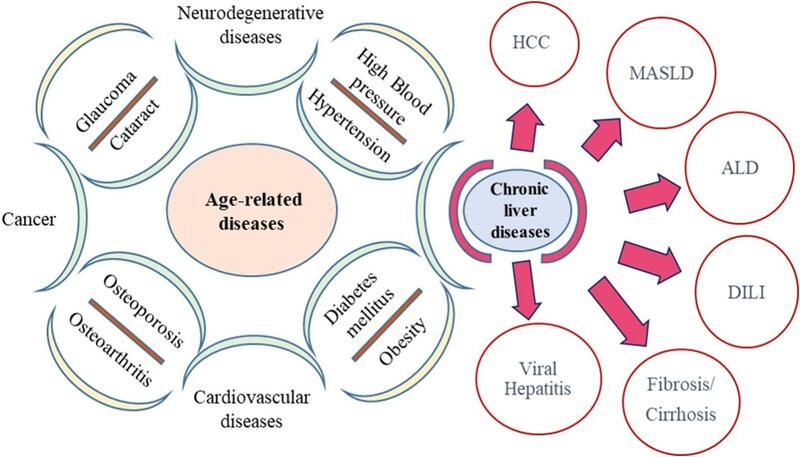

Figure 2. Clinical approach to the older adult with cirrhosis from Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology. The 5Ms of Geriatrics in Gastroenterology, Kochar et al. 2022.

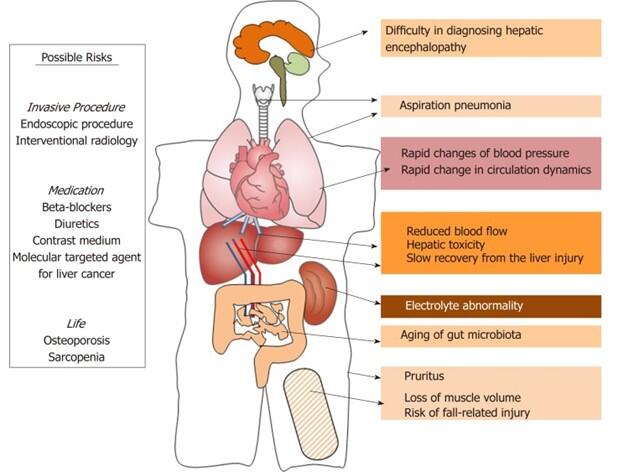

Figure 3. Management Considerations in Elderly Patients from Kamimura 2019. Considerations of elderly factors to manage the complication of liver cirrhosis in elderly patients.

Approach to the older adult with cirrhosis.

Kochar et al have described the 5Ms of Geriatrics in Gastroenterology to describe age-friendly care among older adults in gastroenterology. The 5Ms describe important principles of geriatrics that encapsulate the management of care in older adults. The 5Ms are: Medications, Mind, Mobility, Multicomplexity, and Matters.

Medications.

Medications refer to the polypharmacy that occurs commonly in older adults, commonly defined as ≥5 medications prescribed to an individual. Patients with cirrhosis take an average of 9 medications, many of which can exacerbate geriatric syndromes, including falls, cognitive impairment, and urinary and fecal incontinence. Polypharmacy may impact the safety of many of cirrhosis-related medications and older adults therefore benefit from a careful review of medications and closer monitoring with medication initiation. Specific therapies like steroids are also associated with fall-related injury and osteoporosis associated with reduced underlying bone density that should be monitored closely among older adults.

Mind.

Mind includes prevention, early management, and close monitoring of cognitive disorders among older adults including depression, delirium, and dementia. Among older adults, the development of grade 1 hepatic encephalopathy may be difficult to distinguish from cognitive impairment. Hepatic encephalopathy is often considered to present with acute delirium and asterixis, but hepatic encephalopathy may also have a more attenuated presentation with mild neurological deficit. Additionally, the presentation of hepatic encephalopathy may be similar to other neurological etiologies such as Parkinson’s disease or alcohol-related cognitive impairments like Wernicke encephalopathy. Rarely, cirrhosis can also lead to hepatocerebral degeneration with encephalopathy which can present with apathy, lethargy, somnolence, and/or extrapyramidal symptoms. Among patients with cirrhosis, careful evaluation and management of altered mental status particularly given the risk of hepatic encephalopathy, dementia, and delirium among older adults is important.

Mobility.

Functional status and ability to perform activities of daily living among older adults are critical and safe movement among older adults should be encouraged. Frailty, described in previous posts, is a critical complication of cirrhosis associated with high morbidity and mortality. Emphasis on early detection and treatment including physical therapy with balance exercises such as tai chi, and endurance exercises such as stationary cycling, walking, and bench steps, and nutritional therapy should be pursued in older adults with cirrhosis.

Multicomplexity.

Older adults have multiple comorbidities including age-related syndromes, medical comorbidities, and social comorbidities such as isolation and financial vulnerability. Older adults with cirrhosis have an average of 3 comorbid conditions, including most commonly arthritis, hypertension, and cardiac disease. These comorbidities should be taken into consideration in the management of older adults with cirrhosis. For example, comorbidities like hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure can exacerbate electrolyte abnormalities associated with diuretic use in patients with ascites or volume overload. Kidney dysfunction may impact the choice of medical therapy for patients with cirrhosis. For example, while older adults do not have significant differences in sensitivities to antibiotics, treatment choices among older adults may be impacted by kidney function and possible drug interactions. Due to decreased cardiac function associated with aging and cardiac comorbidities, older adults also have a higher risk of anesthesia associated with endoscopic therapy and initiation of beta blockers. Additionally, older patients may have an increased risk of aspiration pneumonia, particularly with anesthesia associated with endoscopic therapy. Contrast medium can, particularly when monitoring for the development of HCC, among older adults is associated with an increased risk of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) due to age-related decline in kidney function, comorbidities that may increase the risk of CIN such as diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension, and polypharmacy.

Matters.

Older adults with cirrhosis require significantly higher caregiver-related care compared to older adults without cirrhosis. Additionally, the management of HCC, consideration of liver transplantation, the addition of new medications, and palliative care involvement should reflect care that is patient-centered and aligned with patients’ health-related goals. For patients with HCC with good performance status and liver function, aggressive cancer-related therapies can improve survival rates. the treatment of HCC, decision-making should consider patient comorbidities, performance status, and estimated life expectancy. Liver transplantation has also steadily increased among older adults. Between 2002 and 2014, the proportion of liver transplant registrants ≥60 years old rose from 19% to 41%, largely driven by hepatitis C virus, MASLD, and hepatocellular carcinoma. 5-year post-transplant survival benefit is similar among younger and older adults, and liver transplantation among older adults can be successful with careful selection. Among adults ≥ 70 years old, characteristics associated with post-transplant survival include poor functional status and poor kidney function. Finally, given that the median survival in cirrhosis ranges from 2 to 12 years with high physical and psychological symptom burden, all patients with cirrhosis benefit from advanced care planning, goals of care directives, and symptom management. These initiatives are particularly important among older adults. Overall, while age alone does not exclude patients from accessing life-saving therapies, management of older adults with cirrhosis should take into consideration functional status, polypharmacy, comorbidities, and age-related disease processes that may impact patient’s response to such therapies.

Take home points

- The population of patients with liver disease is aging.

- Age-related changes to the liver increases risk of developing fibrosis and cirrhosis among older adults.

- Polypharmacy, co-morbidities, dementia, and frailty may impact the management of older adults with cirrhosis

- Life-saving therapies should remain accessible to older adults with careful selection