Back to Basics: ANA-lyzing Autoimmune Hepatitis

Learning points:

1. Recognize the differences between type 1 and 2 autoimmune hepatitis and clinical manifestations.

2. Describe a framework for the diagnostic evaluation for autoimmune hepatitis.

3. Identify pre-treatment considerations relevant to primary care.

4. Discuss counseling for patients with autoimmune hepatitis who are pregnant or plan to become pregnant.

What is autoimmune hepatitis?

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic, progressive immune-mediated inflammatory liver disease. The inflammation that drives AIH stems from multiple factors including genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors. While AIH can affect individuals of all ages and backgrounds, most adults with AIH are female (71-95%). The age of presentation tends to be bimodal with peaks in the second and fifth decades of life.

AIH is divided into subtypes based on patterns of specific autoantibodies with type 1 (approximately 96% of US adults with AIH) and type 2 AIH as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Differences in age, presentation, and autoantibody patterns between Type 1 and Type 2 autoimmune hepatitis.

| Type 1 AIH | Type 2 AIH | |

| Likely age at onset | Adulthood | Childhood/early teens |

| Female:Male | 4:1 | 10:1 |

| Cirrhosis at diagnosis | Common (28-33%) | Rare |

| Autoantibodies |

|

|

Adapted from Dynamed. ANA: anti-nuclear antibody; ASMA: anti-smooth muscle antibody; SLA: anti-soluble liver antigen antibody; LKM: liver kidney microsome; LC: liver cytosol

Though many patients with AIH have no symptoms, some may experience nonspecific symptoms including fatigue, nausea, and abdominal pain. The physical exam is usually unrevealing apart from stigmata of advanced liver disease if the patient has an acute, severe presentation which can lead to jaundice, or cirrhosis (which can also lead to jaundice, positive fluid wave for ascites, cutaneous changes e.g. spider nevi or palmar erythema, splenomegaly, caput medusa). Physical exam findings may also include manifestations of associated autoimmune diseases like vitiligo, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), or autoimmune thyroid disease.

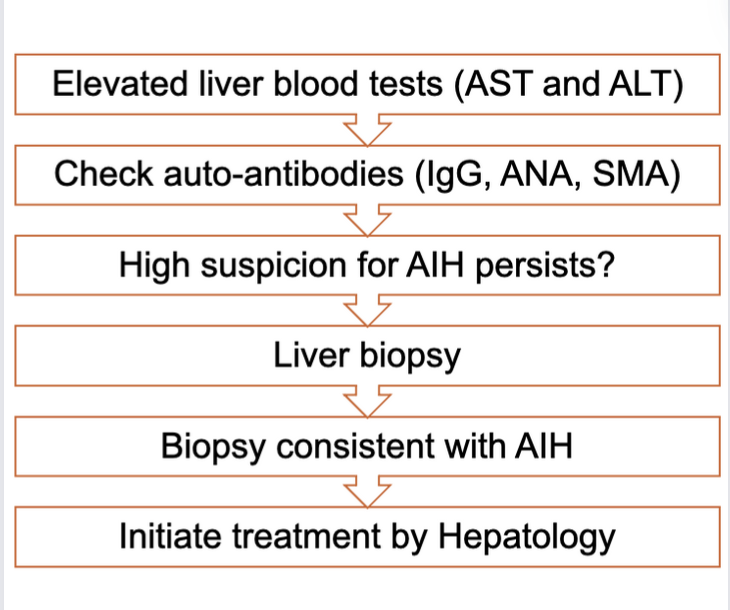

For patients in whom AIH is suspected due to elevated serum aminotransferase levels and/or elevated serum IgG, AASLD guidelines suggest first excluding other competing causes of liver disease. If AIH is still suspected, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) should be assessed in adults. Anti-liver-kidney microsomal type 1 (LKM1) should be added in pediatric patients. If positive, liver biopsy confirms the diagnosis with characteristic histologic findings of interface hepatitis with plasma cell infiltration. If ANA and ASMA are negative, additional serologic workup such as soluble liver antibody (SLA), perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA), tissue transglutaminase (tTG), and anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) can aid in identifying other etiologies of elevated autoantibodies like celiac disease, PSC, PBC, or an overlap syndrome. Notably, approximately 20% of patients with AIH are seronegative. Figure 1 outlines a diagnostic schema for the diagnosis of AIH in adults.

Figure 1: Diagnostic schema for autoimmune hepatitis.

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ANA: anti-nuclear antibody; SMA: anti-smooth muscle antibody; AIH: autoimmune hepatitis.

Many clinicians use the scoring system developed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group or the simplified diagnostic criteria (Table 2) to aid in diagnosis. Imaging studies are not routinely obtained for AIH but may be part of the workup for elevated liver tests.

Table 2. Simplified Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH)

| Variable | Cutoff | Points |

| ANA or ASMA | ≥ 1:40 | 1 |

| ANA or ASMA | ≥ 1:80 | 2* |

| or LKM | ≥ 1:40 | |

| or SLA | Positive | |

| IgG | >ULN | 1 |

| >1.10 times ULN | 2 | |

| Liver histology (evidence of hepatitis is a necessary condition) | Compatible with AIH | 1 |

| Typical AIH | 2 | |

| Absence of viral hepatitis | Yes | 2 |

Adapted from Simplified Criteria for the Diagnosis of Autoimmune Hepatitis. ≥6: probable AIH, ≥7: definite AIH. *Addition of points achieved for all autoantibodies (maximum, 2 points). ANA – antinuclear antibody ASMA – anti-smooth muscle antibody; LKM – anti-liver/kidney microsomal; SLA – soluble liver antibody; IgG – immunoglobulin G; ULN – upper limit of normal.

Though the laboratory workup can be highly suggestive of AIH, liver biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis based on the above criteria. Given the presence of elevated autoantibodies like ANA and ASMA in MASLD and alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), liver biopsy helps in either confirming or ruling out AIH. Furthermore, the presence of AIH in patients despite negative serologic workup (~20% of cases) highlights the importance of liver biopsy to diagnose AIH. On histology, interface hepatitis with plasma cell infiltration is the histological hallmark of AIH though a wide variety of histologic patterns can be seen as outlined in this Pathology Pearls post.

Pre-treatment considerations

- Check thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) activity – detects individuals who are at risk of severe myelosuppression from azathioprine.

- Administer age-specific vaccinations and vaccinations against hepatitis A and B viruses if non-immune.

- Perform bone density assessments in patients at risk for osteoporosis given the possibility of long-term glucocorticoid use. Vitamin D levels should also be checked at diagnosis and annually.

- Screen for celiac and thyroid diseases given disease overlap.

- Monitor for and manage features of metabolic syndrome.

- Assess for barriers to long-term medication adherence including depression and anxiety which is more common in AIH than in the general population.

Pregnancy counseling in AIH

Given the female-predominant distribution of AIH, questions regarding pregnancy and the management of AIH are common. Ideally, biochemical remission should be achieved for 1 year prior to conception. This stems from the association between AIH flares and prematurity. While many of the medications used for the treatment of AIH are safe during pregnancy (e.g., glucocorticoids and azathioprine), mycophenolate mofetil is contraindicated during pregnancy due to its teratogenicity. Sexually active women of childbearing age should be counseled on the use of contraception. Transient immune suppression during pregnancy occurs naturally, but there is a risk of flares in the post-partum period, so women with AIH should be monitored closely for 6 months after delivery.

Take-Home Points:

✔️ Autoimmune hepatitis is an auto-inflammatory liver disease that affects a wide range of individuals with a variety of presentations (asymptomatic to cirrhosis or acute liver failure).

✔️ AIH should be considered in all patients presenting with acute or chronic liver disease.

✔️ The diagnosis of AIH is made through laboratory and histologic evaluation as outlined in the Simplified Diagnostic Criteria for AIH.

✔️ First-line treatment of AIH relies on glucocorticoids and thiopurines, though other medications can be considered when side effects or lack of efficacy are encountered.

✔️ Pre-conception and pregnancy counseling is important and varies based on the pharmacotherapy used.