Back to Basics: Outpatient Management of Cirrhosis

Learning Objectives

In this Back to Basics series post, the learner will be able to:

- Review outpatient management of portal hypertension-related complications and hepatic encephalopathy.

- Learn who and how to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

- Recognize malnutrition as an underrecognized complication of cirrhosis and review dietary recommendations for patients with cirrhosis.

Cirrhosis is characterized by compensated and decompensated stages, with hepatic decompensation being defined by the presence of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), or esophageal variceal bleeding. Management of cirrhosis complications is challenging, particularly in the outpatient setting where time constraints and competing comorbidities limit what can realistically be addressed during a clinic visit. In this article, we provide an overview of important management considerations for patients with cirrhosis in ambulatory clinics. Though an internist in the primary care setting can help manage many of these issues, it is important to realize that a hepatology referral is prudent if a patient requires endoscopy, has decompensated cirrhosis, or develops HCC, as these patients may benefit from advanced therapies or transplant evaluation.

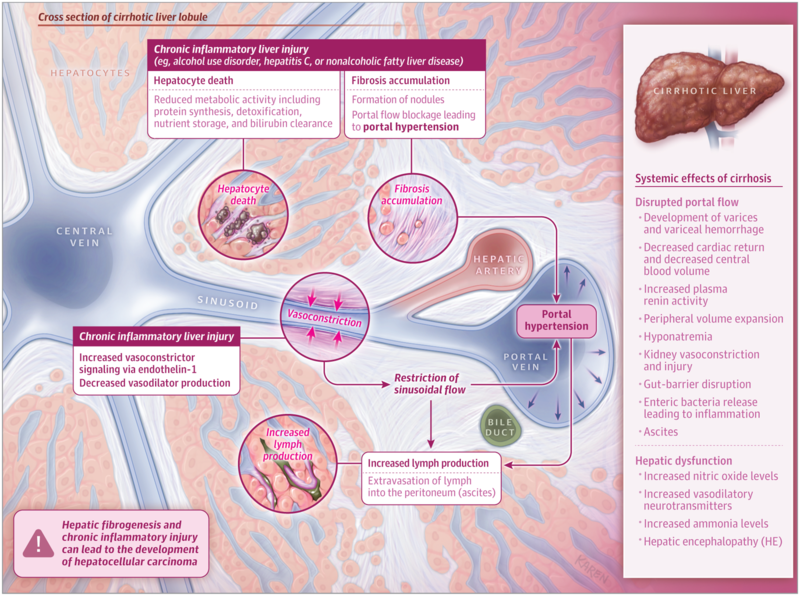

Let’s briefly review pathophysiology of portal hypertension, which will help us better understand outpatient management of cirrhosis:

Figure 1: Cirrhosis causes increased intrahepatic vascular resistance and ultimately portal hypertension. Portal hypertension promotes the release of nitric oxide in the splanchnic vasculature, resulting in splanchnic vasodilation and a reduction in the effective arterial blood volume (EABV). In turn, this activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), the sympathetic nervous system, and the release of anti-diuretic hormone (ADH). These mechanisms promote sodium and water retention, leading to ascites formation. Source: Tapper and Parikh.

Ascites

- Physical exam signs of ascites include abdominal distension, shifting dullness, and fluid waves. Lower extremity edema is also commonly seen in these patients.

- In patients with ascites, dietary sodium restriction to <2 grams/day should be considered. However, this must be balanced against the risk of malnutrition, as discussed below. Fluid restriction is not necessary unless hyponatremia is present.

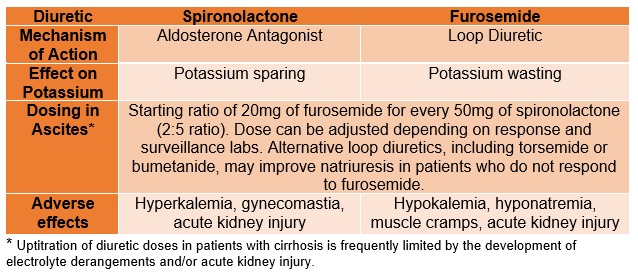

- Dietary sodium restriction alone is inadequate in most patients with ascites, necessitating the use of diuretics

- Aldosterone antagonists (e.g., spironolactone) and loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide) are the main diuretics used in the treatment of cirrhotic ascites (see LFN Quick Tips on ascites). See Table 1.

Table 1: Diuretic use in patients with ascites

- Medications that reduce renal perfusion or increase the risk of acute kidney injury should be avoided in patients with ascites. These include NSAIDS, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs.

- In patients who have refractory ascites (i.e., no response to maximum tolerated dose of diuretics or development of adverse effects on diuretics), large-volume paracentesis with albumin replacement (for > 5L fluid removed) is considered first-line treatment.

- Patients with refractory ascites can be considered for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement.

- Referral for peritoneal drainage catheter placement should be avoided due to their risk of being a nidus for peritonitis. Peritoneal drains can be considered as palliative therapy if a patient is receiving hospice care.

Hepatic Encephalopathy

- Hepatic Encephalopathy (HE) is a clinical diagnosis. However, psychometric testing can help in the diagnosis of minimal and covert HE, as asterixis and disorientation are not present in these stages of HE.

- First line therapy is lactulose, titrated to 2-3 bowel movements (BMs) per day. Check out the LFN Quick Tips on Hepatic Encephalopathy!

- It is important to note that excessive bowel movements (beyond 2-3 daily BMs) may predispose patients to hypovolemia and are unlikely to provide additional protection against HE. In fact, dehydration due to lactulose-related diarrhea is associated with recurrence of HE.

- There is emerging data that the addition of stool consistency complements BM frequency as a patient-reported outcome to lower 6-month total admission and lower HE-related admission to the hospital.

- If a patient has persistent struggles with hepatic encephalopathy despite use of lactulose, or has recurrent admissions for encephalopathy, rifaximin can be added to the regimen

- If an outpatient presents with West Haven Grade 2-3 HE, they should be brought to the hospital to identify and treat the precipitating factor(s). Please see this Back to Basics post for more details!

Esophageal Varices

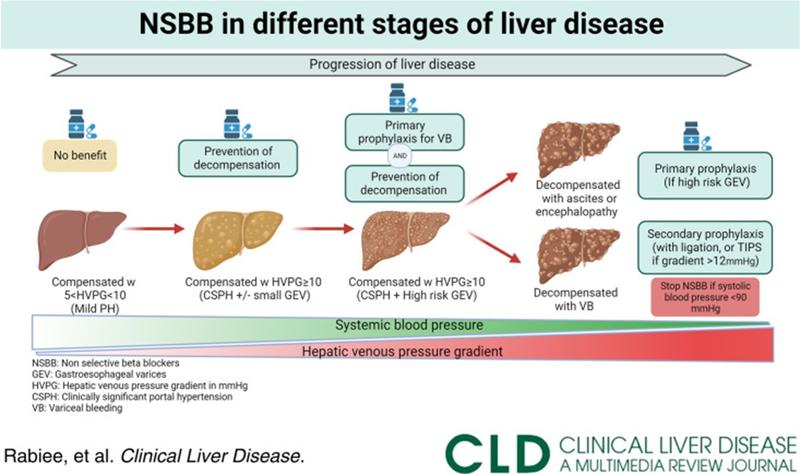

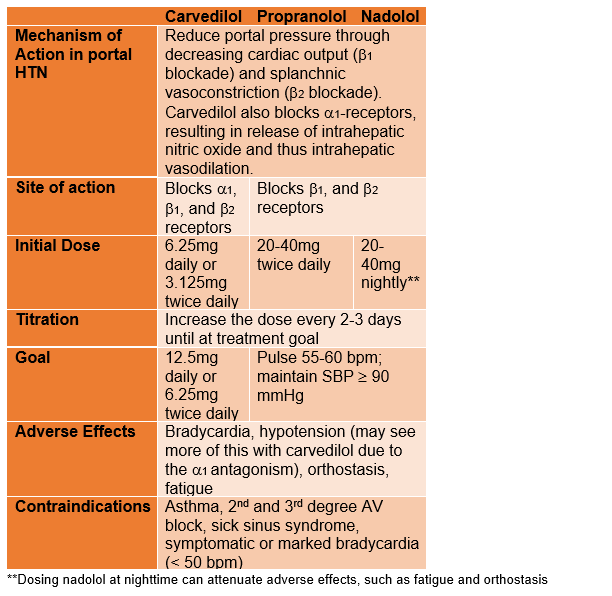

- Traditionally, endoscopy had been used to risk stratify variceal bleeding risk and guide the initiation of non-selective beta blockers (NSBB) based on variceal size. Recently, focus has shifted to preventing decompensating events altogether through noninvasive techniques like transient elastography (TE) and initiation of NSBBs earlier in the disease course.

- This paradigm shift is due in large part to the PREDESCI study. This multi-center randomized controlled trial showed that non-selective beta blockers (NSBB) can prevent hepatic decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis and clinically-significant portal hypertension (CSPH).

Table 2: Beta-blockers in portal hypertension

- Patients with compensated cirrhosis are at highest risk of hepatic decompensation once they develop CSPH, which is defined by portal pressure gradients ³ 10 mmHg. CSPH can be diagnosed non-invasively using TE and platelet (PLT) count cutoffs based on the Baveno VII criteria.

- So, when should you start NSBB? The 2023 AASLD guidelines state that NSBBs should be considered in patients with compensated cirrhosis and CSPH to prevent decompensation.

- CSPH = liver stiffness >25 kPa on TE or evidence of portal HTN endoscopically (varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy, etc…) or radiographically (varices, portosystemic shunts).

- Patients with compensated cirrhosis who are already on NSBBs do not require endoscopy for variceal screening. If a patient with cirrhosis is on a selective beta blocker for a different indication, consider switching to a NSBB (carvedilol preferred).

- Patients with cirrhosis should undergo endoscopic variceal surveillance if they are not a candidate for empiric NSBB. EGD surveillance intervals (generally every 2-3 years) vary based on liver disease activity, variceal status, and whether or not variceal banding was performed.

Figure 2: As cirrhosis progresses, the role of non-selective beta blockers changes, as outlined in this figure from Rabiee and Rabiee. NSBBs can be used to prevent decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis with CSPH and serve as primary prophylaxis for variceal bleeding. Once a patient has decompensated cirrhosis, NSBBs can play a role in primary or secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding, provided a patient’s blood pressure can tolerate the medication.

- Patients with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis B are at increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with an annual incidence of ³ 1.0% and ³ 0.2%, respectively.

Pathophysiology pearl: HBV increases the risk of HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis. As a DNA virus, it can integrate into the host genome, thereby leading to genomic instability and mutations. In contrast, HCV is an RNA virus and does not integrate into the host genome.

- The 2023 AASLD guidelines recommend that patients with cirrhosis and subset populations of patients with chronic hepatitis B undergo HCC screening every 6 months with abdominal ultrasound and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) testing.

- Patients with abnormal findings on screening abdominal ultrasound may require follow-up imaging with contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging (triple phase CT or MRI) based on the 2023 AASLD guidelines.

Malnutrition in Cirrhosis

- Malnutrition is common but underrecognized in patients with cirrhosis, who are in a constant catabolic state leading to muscle wasting.

- Evaluate co-occurring conditions that may contribute to malnutrition, including food insecurity and periodontal disease.

- Recent AASLD guidelines recommend screening patients with cirrhosis for micronutrient deficiencies annually. These include vitamin D, vitamin E, folate, thiamine, zinc, and selenium deficiencies.

- Bone density screening with DEXA scans should be obtained in patients with cirrhosis, particularly those with cholestatic liver disease, at time of diagnosis and periodically thereafter.

- The goal caloric intake for nonobese patients is 35 kcal/kg/day. The goal caloric intake for obese cirrhosis patients is stratified by BMI. Target 25-35 kcal/kg/day for patients with BMI 30-40 kg/m2 and 20-25 kcal/kg/day for individuals with BMI ³40 kg/m2.

- AASLD guidelines recommend a goal daily protein intake of 1.2-1.5 g/kg ideal body weight. Protein intake should not be restricted in patients with hepatic encephalopathy.

- Minimize fasting time to 3-4 hour intervals. To reduce evening fasting time, patients can eat an early breakfast and/or a late-night high protein snack.

- Sodium restriction will prevent fluid retention but may decrease the palatability of food, creating a barrier to adequate oral intake. Liberalization of sodium restriction should be considered in patients who are malnourished on a sodium-restricted diet.

Take home points:

- Frontline management of ascites and lower extremity edema in cirrhosis includes sodium restriction and diuretics. Patients should be referred for paracentesis, and considered for TIPS, if they are intolerant or refractory to diuretics.

- Refer patients with decompensated cirrhosis or HCC to hepatology for consideration of liver transplant evaluation.

- Non-selective beta blockers are beneficial in patients with portal hypertension and can prevent/delay complications of variceal bleeding and ascites.

- Patients with cirrhosis should be screened for HCC every 6 months and malnutrition at least every 12 months.

| Outpatient Cirrhosis Checklist |

|

Ascites: ☐ Discuss sodium restriction, monitoring daily weights ☐ Consider diuresis

☐ Assess need for paracentesis |

|

Hepatic Encephalopathy: ☐ Are symptoms present? ☐ Is pharmacotherapy indicated or already prescribed?

|

|

Esophageal Varices: ☐ Start non-selective beta blocker if signs of portal hypertension present

☐ If beta-blockers aren’t an option, proceed with EGD for screening |

|

HCC screening: ☐ RUQ US + AFP or contrasted CT/MRI every 6 months |

|

Metabolism and Nutrition: ☐ Screen for micronutrient deficiencies annually ☐ Bone density screening at cirrhosis diagnosis and periodically as indicated afterwards ☐ Dietary

|

|

Vaccinations: ☐ Hepatitis A ☐ Hepatitis B ☐ Pneumococcal ☐ Recombinant Zoster (if ≥50 years of age) ☐ Influenza ☐ COVID-19 |

|

Referral for transplant evaluation: ☐ Consider in any patient with jaundice, decompensated cirrhosis, or HCC |