Hepatitis D-Mystified

What is Hepatitis Delta Virus?

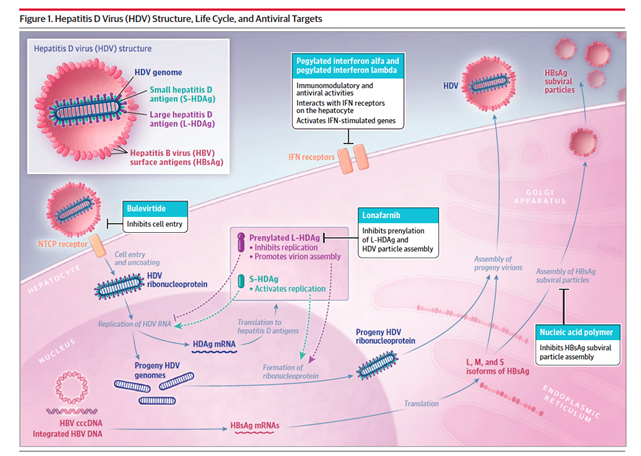

HDV is a single-stranded RNA virus that depends on the presence of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) to enter and exit hepatocytes and sustain its replication. The HDV genome encodes the HDV antigen (HDAg), which has two isoforms, a larger and a smaller isoform. These two HDAg isoforms then bind to the HDV RNA genome to form a ribonucleoprotein which is surrounded by an envelope containing the isoforms of the Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). HDV entry into hepatocytes is facilitated through three HBV envelope proteins. By sharing the same receptors for hepatocyte entry as the HBV, the HDV particle enters the hepatocyte. Interestingly, HDV suppresses HBV replication, although the mechanism behind this is not well understood. While inside the hepatocyte, HDV replication is independent of HBV. The HDV borrows the host RNA polymerase and does not encode any protein with enzymatic activity. This unique interplay between HBV and HDV and the ability of HDV replication in the absence of HBV makes it difficult to eradicate chronic HDV infection.

HDV infection occurs through two potential pathways: coinfection and superinfection. Coinfection occurs when patients are dually infected with HBV and HDV, and superinfection occurs when a patient with underlying HBV develops new HDV. Prevalence studies on HDV have been highly variable due to both geographic differences and differences in the quality of data. In light of these known limitations, prevalence of HDV in chronic HBV has been estimated to be anywhere from 6 to 14%. These studies did include patients who were foreign-born; therefore, many HDV initial infections likely occurred outside of the United States.

Who Should Receive Screening for HDV?

The 2023 EASL clinical practice guidelines on hepatitis delta virus (HDV) recommend screening for HDV in all HBsAg-positive individuals. This contrasts with the AASLD guidelines which recommend risk-based screening for HDV. These high-risk groups include individuals with HIV, persons who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and patients from endemic areas. However, the AASLD guidelines do recommend screening if there is any uncertainty regarding risk profile or concern for infection. Recent literature has shown that risk-based strategies may miss a significant number of individuals infected with HDV. Re-testing for HDV is also recommended in individuals with high-risk behavior for reinfection and in areas with a high prevalence of HDV, particularly during acute decompensation of liver disease or elevations in liver enzymes.

Diagnosis of HDV

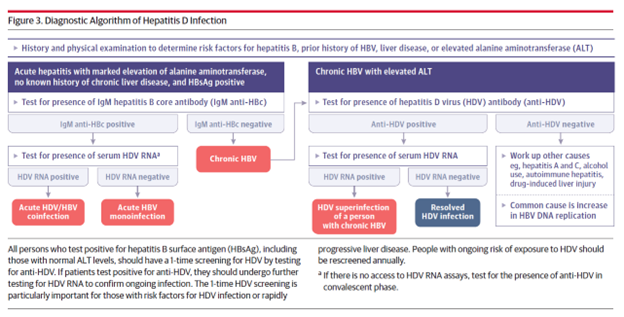

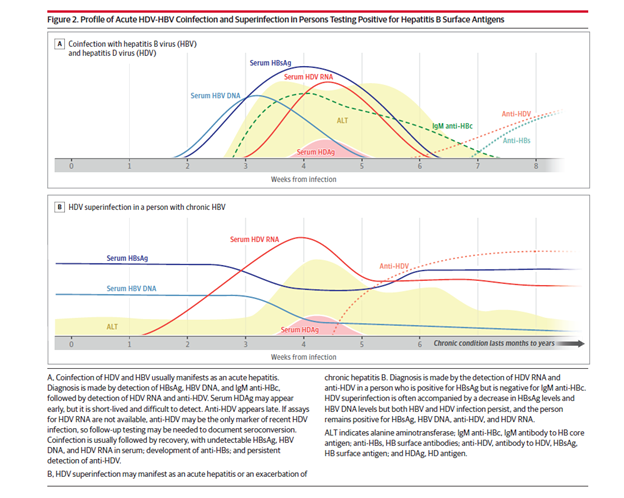

The initial screening test for HDV is serum analysis for anti-HDV antibodies. If these come back positive, further workup is needed. Acute HBV/HDV coinfection is diagnosed by the presence of HBsAg and Hepatitis B Core IgM along with a positive HDV RNA. The serum HDV Ag may only be positive for a few days and HDV antibody production may be delayed, and thus acute infection should be evaluated with a HDV RNA level. Patients with chronic HBV who are presenting with HDV superinfection often have a hepatitis B core IgM that is negative. Depending on the acuity of the superinfection, HDV antibodies may still be negative, and evaluation with a HDV RNA may also be warranted.

Figures 2 and 3. from Negro et al below present diagnostic algorithms and profiles of HBV and HDV infections.

Clinical Manifestations

HDV transmission is similar to HBV and includes exposure to contaminated needles, sharing of contaminated household materials like toothbrushes, razors, exposure to unsterilized equipment during medical procedures, injection drug use, and sexual intercourse. Coinfection with HBV and HDV usually leads to an acute hepatitis and the majority (about 95%) of patients eventually clear both viruses. Fulminant hepatitis and acute liver failure are severe manifestations of HBV/HDV coinfection and are more common than in HBV mono-infection. Studies indicate that the prevalence of HDV coinfection is as high as 35-40% in fulminant hepatitis B compared to 4-20% in non-fulminant hepatitis. Superinfection with HDV in patients with chronic HBV leads to chronic HBV-HDV infection in about 90% of patients.

The clinical course of chronic HDV is associated with a more rapid and frequent progression to cirrhosis, subsequent liver related mortality, and hepatocellular carcinoma compared to HBV mono-infection. Some studies indicate that up to 15% of patients can progress to cirrhosis in 3 years. Even in the absence of this ultra-rapid phenotype, patients with chronic HDV/HBV typically have a more severe course than patients with HBV mono-infection. The odds of developing HCC in HBV/HDV are almost three times the odds in HBV mono-infection.

That being said, there is some variability in clinical course and severity of liver disease, which are likely influenced by both host factors and HDV genotypes. Testing for genotypes is imperfect, however, and access to reliable diagnostic modalities is challenging. As of now, testing for distinct genotypes does not alter management, so is not widely recommended.

You’ve Diagnosed HDV – Now What?

Clinical monitoring in patients with untreated HDV infection includes a baseline diagnostic assessment and identification of changes in disease activity. Since non-invasive tests (aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio and FIB-4 testing) for fibrosis are not validated in Hepatitis D, a combination of laboratory findings and imaging including abdominal ultrasound are needed to determine the severity of liver disease. The presence of inflammation has the potential to overestimate the degree of fibrosis measured by non-invasive tests including ALT and transient elastography (TE). The severity of transaminase elevation, the degree of thrombocytopenia, tests of liver synthetic function, and abdominal imaging can help further guide our assessment. Data on TE in the staging CHD is scarce, and should be interpreted with caution in these patients. However, recent data suggests it may perform as well in patient with HBV and HCV, but further studies are needed to validate this. Equivocal results may warrant evaluation with a liver biopsy.

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard to evaluate fibrosis in HDV, and may be used when the results would alter management, It can be particularly helpful when non-invasive testing is discordant, or if there is concern for a co-occurring chronic liver disease, such as autoimmune hepatitis or steatotic liver disease.

HDV Treatment:

HDV RNA level should be monitored at least yearly in untreated patients as persistent HDV viremia is associated with poor outcomes. Spontaneous fluctuations in HDV RNA levels can occur and may be associated with changes in aminotransferases. HBV DNA and HBsAg levels should also be monitored yearly and during major fluctuations of HDV RNA or ALT levels as relapses of HBV replication are reported with HDV clearance. Seroconversion of HbsAg can also occur with clearance of HDV RNA. Finally, due to the higher risk of HCC in patients with chronic HDV, all patients, regardless of fibrosis stage, should receive HCC surveillance every 6 months.

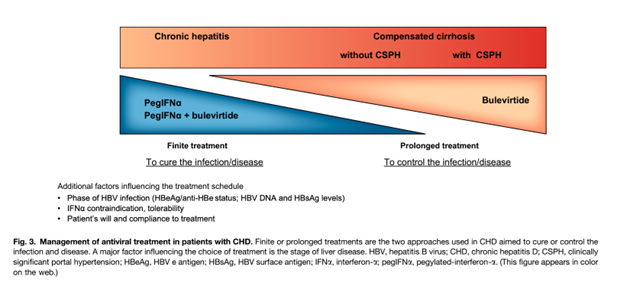

The only treatment available in the United States aimed at HDV clearance is pegylated interferon alfa (PEGIFNα). Because PEGIFNα has a terrible side effect profile, the indications for HDV treatment include active disease (elevated ALT/hepatitis on biopsy and elevated HDV RNA levels) or patients with significant fibrosis. As discussed previously, chronic HDV is associated with a more rapid progression to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. The goal of treatment is to reduce progression of liver disease. Treatment-induced suppression of HDV infection results in clinical benefits including prevention of decompensated liver disease. HBV antiviral therapies to control co-occurring HBV are important in the management of HBV/HDV, but are used to control HBV activity rather than target clearance of HDV.

When Should You Use Pegylated Interferon?

Standard interferon-α (IFNα) and pegylated interferon-α (PEGIFNα) therapies have been the only antiviral therapies for chronic HDV infection until recent development of bulevirtide. The mechanisms of antiviral agents in chronic HDV infection are illustrated in Figure 1. In chronic hepatitis D infection, an effective pegIFNα treatment response leads to reduction of both HBV and HDV DNA. However, the reduction of HBV DNA has no effect on HDV RNA levels as HDV is dependent only on HbsAg to sustain its entry into hepatocytes; HDV does not depend on HBV for replication. The specific mechanism of action of pegIFNα is not clear. Proposed mechanisms derived from in vitro studies include an inhibitory effect on viral entry into hepatocytes and suppression of cell division. Data for IFNα in chronic HDV infection is supported by the two randomized control trials, HIDIT-I and HIDIT-II. The recommended duration of pegIFN2α therapy is 180 mcg once a week subcutaneously for 48 weeks. Serum HDV RNA levels at 24 weeks after treatment are the strongest predictor of treatment response. However, the identification of non-response (<1 log HDV RNA decline) is modest using HDV RNA levels at week 24 of therapy with 67% sensitivity and 85% specificity. PEGIFNα can be used in patients with compensated cirrhosis but it is contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. A major limiting factor of PEGIFNα is substantial patient side effects that often necessitate discontinuation.

Treatment success with PEG-IFNα is limited; studies demonstrate 23-57% of patients may achieve undetectable HDV RNA levels after 24 weeks of treatment. Late relapse is also somewhat common. Longer durations of PEG-IFNα are not associated with better response, and thus are not recommended. However, a new formulation of PEG-IFNα, called PEG-IFN-lambda (PEG-IFN-λ), may demonstrate better results. In a Phase 2 open-label study of PEG-IFN-λ, 36% of patients in the high dose group experienced virologic response, which was sustained for at least 24 weeks.

Bulevirtide in CHD infection

Bulevirtide (BLV) is a synthetic lipopeptide consisting of domains of the HBsAg protein that inhibits entry of HDV (and HBV) into hepatocytes by binding and inactivating the Sodium taurochoate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP), which is a protein expressed on the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes. Bulvertide is administered as a daily subcutaneous injection and is well-tolerated. Data from phase 2 trials show a significant reduction in HDV RNA levels and an even higher response in treatment rates when combined with pegIFNα. Figure 3. highlights therapeutic approaches in chronic HDV infection. Data supporting the use of BLV in chronic HDV infection show that about 40-65% of patients treated with BLV monotherapy achieve a >2log decline in HDV RNA and normalization of ALT levels after a 48 week treatment course. The optimal duration of treatment for BLV is not known and the recommended strategy is to continue treatment beyond one year for maintenance and increase in the virologic response What sets BLV apart is its superior side effect profile and is role in advanced cirrhosis with preliminary data showing a significant improvement in liver function tests and even resolution of esophageal varices. BLV is only approved in the European Union (EU) and is not yet FDA-approved in the US.

Take Home Points:

- HDV is an RNA virus that requires the presence of HBV to cause a chronic hepatitis.

- Patients with HDV coinfection experience higher rates of HCC and more rapid progression of liver disease than patients with HBV alone.

- Screening for HDV in at-risk patients can guide management and improve HBV/HDV-related outcomes.

- Current treatment options for HDV in the USA are limited to interferon-based therapies, however, data from clinical trials support the use of bulevirtide which has approval in Europe.

- Preliminary data supports the use of BLV in advanced cirrhosis in contrast to pegIFNα

- Undetectable HDV load at 24 weeks of PEGIFNα treatment is associated with an extremely high likelihood of virological response after treatment.