What happens to the liver when blood vessels go rogue

What is hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia?

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an autosomal dominant inherited vascular disorder characterized by mucocutaneous and gastrointestinal telangiectasias as well as arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) involving the pulmonary, hepatic and cerebral circulations. HHT is also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu named after the physicians who researched the condition in the 1890’s. HHT can be caused by variants in multiple genes related to the tumor growth factor beta (TGFß) signaling pathway, involved in the development and maintenance of arteries and veins. The three major disease-associated genes are ENG (HHT1), ACVRL1 (HHT2) and SMAD4 (juvenile polyposis-HHT overlap). Pulmonary and cerebral AVMs are more common in HHT1 while hepatic AVMs, non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and pulmonary hypertension are more common in patients with HHT2.

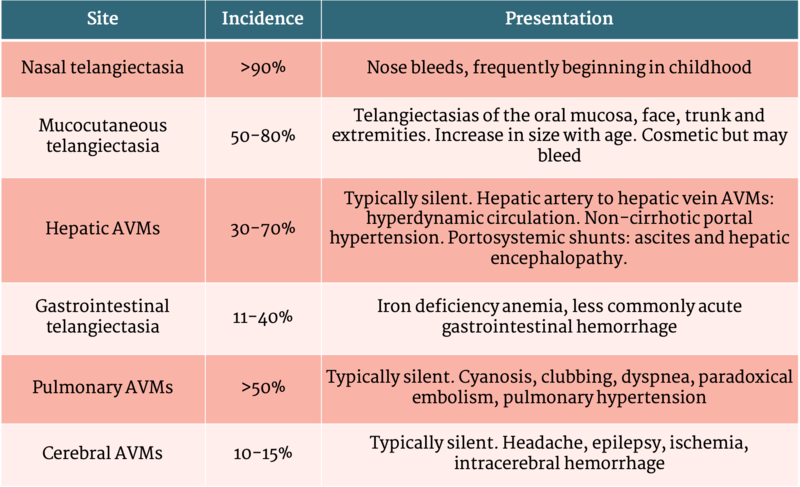

Table 1 - Clinical presentation of HHT

What happens when HHT involves the liver?

Hepatic involvement of HHT occurs in up to 70% of patients but is usually silent. Symptoms, if present, are related to the different patterns of vascular involvement.

Large hepatic AVMs between the hepatic artery and hepatic vein can cause significant left to right shunts. These shunts increase cardiac output and can lead to high output heart failure and angina. Biliary ischemia and cholestasis may occur as a result of the decrease in blood flow through the hepatic artery. In rare instances, biliary ischemia can lead to bile duct and liver necrosis known as “hepatic disintegration”.

Shunts between the hepatic artery and portal vein can lead to a significant increase in portal blood flow and the deposition of fibrous tissue in the liver. This fibrous tissue causes a type of pseudocirrhosis. Patients may present with ascites, hepatic encephalopathy and other symptoms related to portal hypertension. Portal hypertension may also occur as a result of nodular regenerative hyperplasia

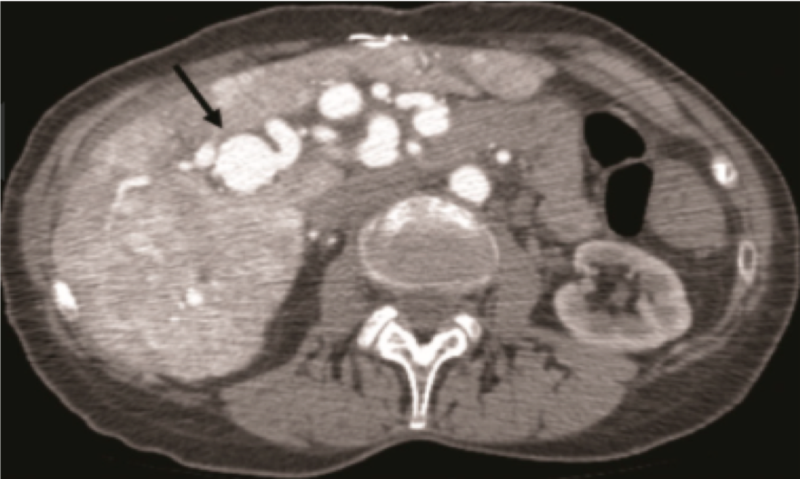

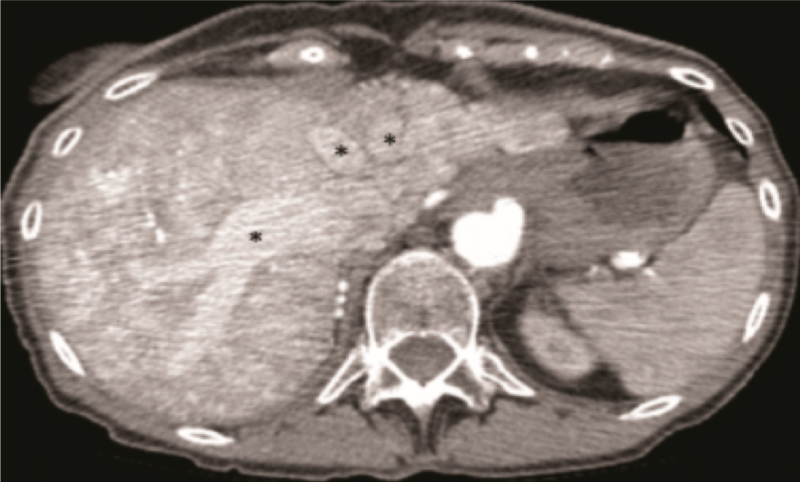

Figure 1 - CT angiogram demonstrating arteriosystemic shunting in a patient with HHT. Right hepatic artery aneurysm with significant dilation (arrow). Hepatic arterial to hepatic venous shunting (*).

How should the diagnosis of HHT be made?

- Spontaneous and recurrent epistaxis

- Mucocutaneous telangiectasias at characteristic sites (i.e oral mucosa, face, trunk and extremities)

- Visceral involvement (gastrointestinal telangiectasias; pulmonary, hepatic or cerebral AVMs)

- A first-degree relative with HHT

Diagnosis is defined as “definite” (3+ criteria), “suspected” (2 criteria) or “unlikely” (1 criteria). The diagnosis can be confirmed with genetic testing and identification of a pathogenic variant in the ENG, ACVRL1 or SMAD4 genes. However, genetic testing does not detect all variants and HHT has variable penetrance and expression.

How is hepatic HHT managed?

No treatment is recommended for patients with asymptomatic hepatic HHT. Patients with portal hypertension related to HHT should follow the same treatment guidelines for portal hypertension related to cirrhosis. Those patients with high-output heart failure related to hepatic AVMs should be treated with standard therapy for heart failure. Antiangiogenic therapy with IV Bevacizumab should be considered in patients with symptomatic high-output heart failure due to hepatic AVMs that has failed to respond to standard heart-failure therapies.

Biliary disease related to HHT can be treated with ursodeoxycholic acid, though there has been no evidence that it provides a significant benefit. To avoid cholangitis, patients with biliary abnormalities should not have invasive biliary procedures. When cholangitis does develop, it should be managed with antibiotics and biliary drainage when necessary.

Liver transplantation is the only curative treatment for hepatic HHT and is the treatment of choice for patients who fail intensive medical management. Liver transplantation should be considered in acute biliary necrosis, intractable heart failure and portal hypertension. Though HHT is an uncommon indication for liver transplantation, ten-year patient and graft survival outcomes are similar to patients receiving liver transplants for other indications.