Why is retrograde transvenous obliteration used to treat gastrofundal variceal bleeding?

Acute variceal hemorrhage is a serious complication of cirrhosis associated with 6-week mortality of 10-15%. The mainstays of treatment include resuscitation, vasoactive therapy to reduce portal pressure, prophylactic antibiotics, and early upper endoscopy within 12 hours of presentation to identify the source of bleeding.

Bleeding from gastric varices is far less common compared to esophageal varices, estimated to account for 11% of variceal bleeds. However, compared to esophageal variceal bleeding, bleeding from gastric varices is considered more severe and difficult to treat, with 1 year mortality as high as 43%.The increased severity is attributed to larger size and higher blood flow of gastric varices, especially in the fundus, which are more prone to hemorrhage and endoscopic treatment failure. The optimal management of gastric varices is based on patient characteristics and center expertise. First-line options include endoscopic cyanoacrylate glue injection, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS), and retrograde transvenous obliteration (RTO).

This post will focus on why RTO is increasingly utilized in the last two decades in the treatment of gastrofundal variceal bleeding.

What is the Pathophysiology and Types of Gastric Varices?

Varices are portosystemic collateral vessels that develop as a direct consequence of portal hypertension. They most commonly develop in the esophagus and stomach, but can also develop in the rectum, duodenum, and surgical stomas.

Gastric varices are found in about 20% patients with cirrhosis. The Sarin Classification describes four types of gastric varices based on endoscopic location summarized below.

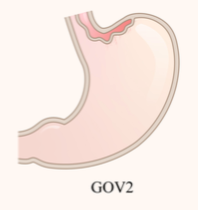

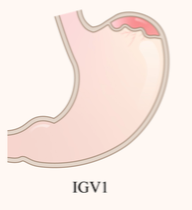

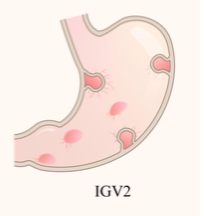

| Sarin type | Estimated % of gastric varices | Location | Diagram |

| Gastroesophageal varices type 1 (GOV1) | 75 | Esophagus and lesser curvature of the stomach |

|

| Gastroesophageal varices type 2 (GOV2) | 21 | Esophagus, fundus, and greater curvature of the stomach |

|

| Isolated gastric varices type 1 (IGV1) | 1.6 | Fundus |

|

| Isolated gastric varices type 2 (IGV2) | 4 | Any part of the stomach other than the fundus |

|

Figure adapted from Luo et al. Update on the management of gastric varices. Liver International. 07 February 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35129288/

Characterizing the location of gastric varices is clinically important because varices involving the gastric fundus (GOV2 and IGV1) are associated with greater risk of bleeding. The 2-year incidence of bleeding is 78% for IGV1 and 55% for GOV2, which is significantly higher than GOV1 (11.8%) and IGV2 (9%).There is evidence that portosystemic collateral flow increases at the expense of reduced portal venous flow and that patients with gastric varices bleed at lower portal pressure (HVPG <12mmHg) compared to esophageal varices. Other predictors of bleeding include varix size >10mm for gastrofundal varices, presence of red marks, and poorer liver function.

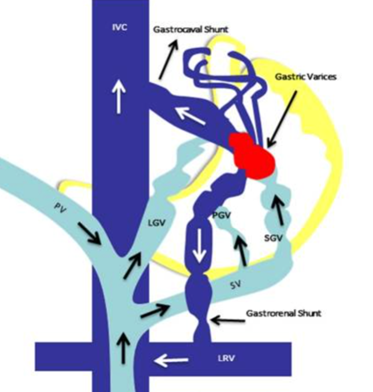

Understanding the afferent blood supply and efferent drainage of gastrofundal varices is important for understanding why retrograde transvenous obliteration (RTO) is possible. Distinct from esophageal varices and GOV1, which are supplied by the left gastric vein and drain into the superior vena cava, gastrofundal varices are supplied by the posterior gastric vein and short gastric veins and drain most commonly into the left renal vein through a gastrorenal shunt (GRS) or less commonly into the IVC through a gastrocaval shunt. These large portosystemic shunts are targeted in various RTO strategies.

Figure adapted from: Philips et al. Beyond the scope and the glue: update on evaluation and management of gastric varices. BMC Gastroenterology. 2020 Oct 30;20:361. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33126847/

How does RTO work?

The concept of RTO was first described in 1984 by Olson et al in the United States, but it was mostly performed and further developed in Japan and South Korea. The first successful balloon-occluded RTO (BRTO) was reported in 1996 by Kanagawa et al.In the last 2 decades, RTO techniques have been increasingly performed in the U.S.

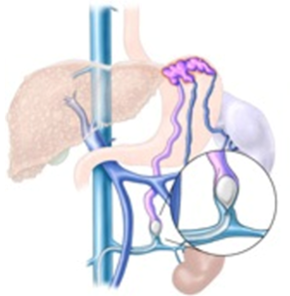

The aim of RTO is to eliminate a gastrofundal varix that is actively bleeding or recently bled by accessing the gastrorenal shunt draining the varices and injecting a sclerosing agent in the traditional balloon occluded RTO (BRTO) approach. More recently, advancements in the field have expanded to include use of embolic agents, coils (in coil-assisted RTO, also called CARTO), and/or vascular plugs (in plug-assisted RTO, also called PARTO) to achieve eradication of the gastric variceal complex.These approaches are described in the table below.

| Approach | Access | Intervention | Considerations | Diagram |

| Balloon occluded RTO (BRTO) | A catheter is inserted in the femoral vein and advanced through the IVC, left renal vein, and finally to the gastrorenal shunt (GRS) that drains the gastrofundal varix complex. | A balloon is inflated to occlude the GRS, and a sclerosing agent is injected retrograde. | Traditional BRTO historically carried higher procedural burden due to having to leave the inflated balloon up to 36 hours to prevent escape of sclerosant into portal or systemic circulation. The modified BRTO technique used in current practice incorporates coils and vascular plugs to avoid this. |

|

|

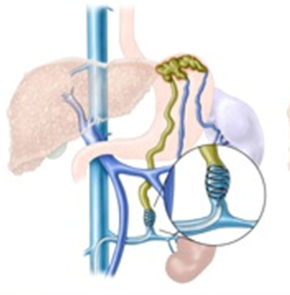

Plug-assisted RTO (PARTO) |

Permanent vascular plug is deployed at GRS, and an embolizing Gelfoam slurry is injected retrograde. | Limited use when GRS is larger than largest plug (18mm) or anatomy is tortuous |

|

|

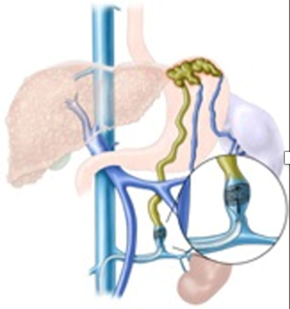

| Coil-assisted RTO (CARTO) | A permanent coil is deployed at the GRS, and an embolizing Gelfoam slurry is injected. | Can be size-adjusted to a large GRS |

|

Figures adapted from: AASLD Practice Guidance on the use of TIPS, variceal embolization, and retrograde transvenous obliteration in the management of variceal hemorrhage. Hepatology79(1):224-250, January 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37390489/

A 2015 meta-analysis of 1,016 patients from 24 studies demonstrated that BRTO is a safe and effective treatment for gastrofundal varices with a high rate of technical (96.4%) and clinical success (97.3%).Rebleeding rate is under 10% and as low as 2.7%. A 2021 randomized control trial comparing rebleeding rates in patients with bleeding gastrofundal varices who were treated with endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection or BRTO found BRTO was superior with a lower all-cause rebleeding rate at 1 and 2 years (77% vs. 96.3% and 65.2% vs. 92.6%, respectively, p = 0.004) with no difference in survival. Determining the optimal approach to RTO is an area of ongoing research.

What are the indications for RTO in gastrofundal variceal bleeding?

The 2024 AASLD Practice Guidance recommends endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection for initial management of gastric variceal bleeding. TIPS or RTO should be considered for uncontrolled gastric variceal bleeding or secondary prophylaxis. RTO is preferred if there are contraindications to TIPS. These include severe hepatic encephalopathy, Child-Pugh >13 points, and high MELD (no specific MELD cutoff is recommended but higher scores are associated with higher mortality). Patients with bleeding gastric varices should have a contrast-enhanced CT or MRI to have a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s vasculature, specifically to evaluate for a GRS and to exclude thrombosis. A multidisciplinary discussion between hepatology, gastroenterology, and interventional radiology is essential to decide on the optimal treatment that considers the patient’s anatomy, clinical profile, and local expertise.

What are the complications of RTO?

Complications are related to an increase in portal venous pressure that results from obliteration of the previously decompressive portosystemic shunt. Complications include worsening ascites in 22% patients and new or worsening esophageal varices with bleeding in up to 33% of patients. Presence of large esophageal varices or significant ascites often preclude pursuing RTO.

What follow up is required after RTO?

Close-interval repeat imaging with a contrast-enhanced CT should be obtained to ensure complete obliteration of the variceal complex. Where available, endoscopic ultrasound can be used. Society recommendations on timing vary from 2-3 days (AASLD) to 4-6 weeks (AGA). If complete obliteration is not achieved, the patient may require further procedures like endoscopic therapy or TIPS. After successful RTO, given the risk of increased portal pressures, routine upper endoscopy to assess for new development or progression of esophageal varices. The 2024 AASLD Practice Guidance recommends 1-2 months after intervention. The 2021 AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Bleeding Gastric Varices recommend repeat endoscopy 2 weeks if high-risk esophageal varices were present and 6-8 weeks if low-risk varices were present. Treatment of these esophageal varices and use of non-selective beta blockers should depend on existing guidelines and center expertise.

Is there a role for RTO in primary prevention of gastrofundal gastric variceal bleeding?

Not currently. The 2024 AASLD Practice Guidance stated neither RTO nor TIPS should be used to prevent first hemorrhage in patients with gastrofundal varices. This has not been assessed in randomized trials. Limited data from a retrospective analysis of patients treated with RTO for primary prophylaxis suggest a high rate of variceal obliteration but no effect on mortality compared with no intervention.

What about anterograde transvenous obliteration (ATO)?

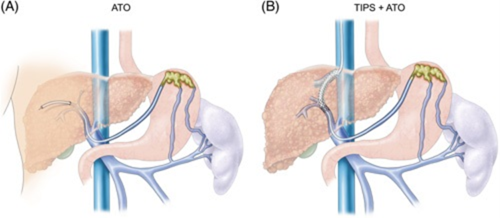

Anterograde transvenous obliteration targets the portal venous inflow that feeds a gastric varix as opposed to the systemic venous outflow that drains it in RTO. The portal venous system is accessed either percutaneously through the liver (left figure below) or spleen, or more commonly, in conjunction with a TIPS (right figure below). The inflow branches of the portal or splenic veins that feed the gastric varix are then treated with sclerosant, embolizing agents, glue, coils, or plugs. ATO is used either as an adjunct or alternative to RTO when a gastrorenal shunt is not present. Coagulopathy and splenic or portal vein thrombosis are contraindications.

Figures adapted from: AASLD Practice Guidance on the use of TIPS, variceal embolization, and retrograde transvenous obliteration in the management of variceal hemorrhage. Hepatology79(1):224-250, January 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37390489/

The technical success of ATO is variable, ranging from 44-100%, because multiple feeding collaterals can supply varices and some of these can be missed. ATO is generally less preferred over RTO because it is more invasive. However, a 2025 study found trans-splenic anterograde coil-assisted transvenous occlusion (TACATO), during which feeder veins are accessed through branches off the splenic vein and occluded with coils and injected with sclerosant, demonstrated comparable efficacy and safety as RTO in secondary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleeding.

Similar to RTO, repeat imaging to confirm complete obliteration of the varices is recommended. Monitoring for worsening portal hypertension, including follow up variceal screening within 1-2 months after ATO, is recommended.

How do these interventions fit into the overall care plan of patients with cirrhosis?

RTO and ATO treat the sequelae of portal hypertension and thus are not definitive treatment strategies. Thus, candidacy for follow-up TIPS and/or liver transplantation should be evaluated for long-term treatment.

Key points:

- While gastric variceal bleeding is less common than esophageal variceal bleeding, gastric variceal bleeding is harder to treat and associated with higher mortality.

- Gastric varices involving the fundus, called GOV2 and IGV1 based on Sarin classification, have the highest risk of bleeding and are the targets of retrograde obliteration techniques (RTO).

- RTO accesses a large portosystemic shunt, most commonly the gastrorenal shunt, that drains the gastrofundal varix and obliterates it with a sclerosing agent.

- RTO can be considered as a first line treatment option for gastrofundal variceal bleeding, rebleeding, or secondary prevention of rebleed. A multidisciplinary approach is essential to decide on the optimal treatment based on the patient’s anatomy and intuitional expertise.

- Complications of RTO are related to increased portal pressure, including ascites and esophageal varix formation and bleeding. Variceal surveillance with upper endoscopy in 1-2 months after RTO is recommended. Earlier repeat endoscopy at 2 weeks can be considered if there are known pre-existing high-risk esophageal varices.

- Follow-up TIPS and/or liver transplantation should be considered for long-term treatment after the resolution of acute gastric variceal bleeding.