Why Timing Matters: Paracentesis on Admission for Cirrhosis with Ascites

When a patient with cirrhosis comes through the hospital doors with ascites, the clock is ticking. Delaying a simple bedside procedure—even by a day—can mean the difference between recovery and death. So why is early paracentesis so critical?

Ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis, and it is also the leading cause of hospital admissions in patients with decompensated liver disease. Those with ascites are at risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), which can occur in up to 10-30% of hospitalized cirrhotic patients and is associated with a high mortality. Management of ascites is an essential skill to master when caring for hepatology patients—and timing matters. If you take care of patients with cirrhosis, you’ll see ascites again and again—but knowing when to act is just as important as knowing how.

What if the ascites is new?

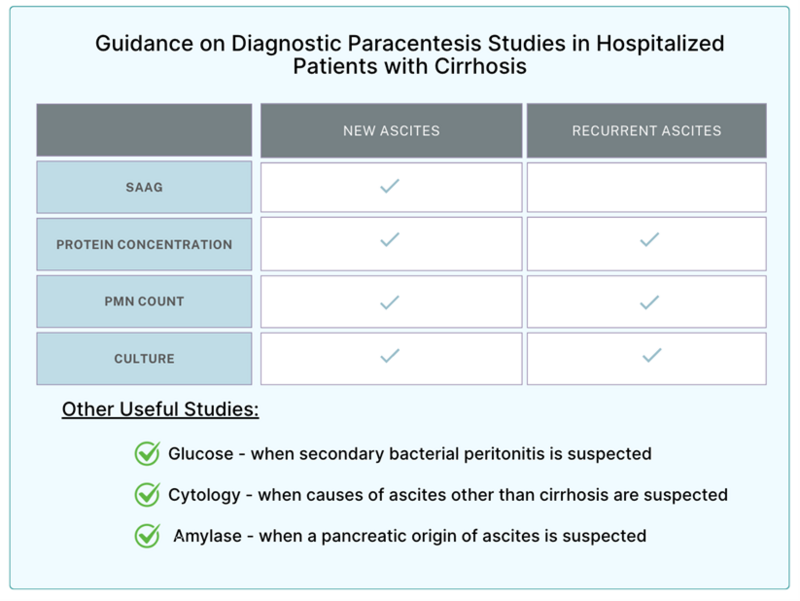

Diagnostic paracentesis is key! There are two reasons paracentesis is needed in this setting (1) to confirm the ascites is related to portal hypertension (or not), and (2) to evaluate for SBP.

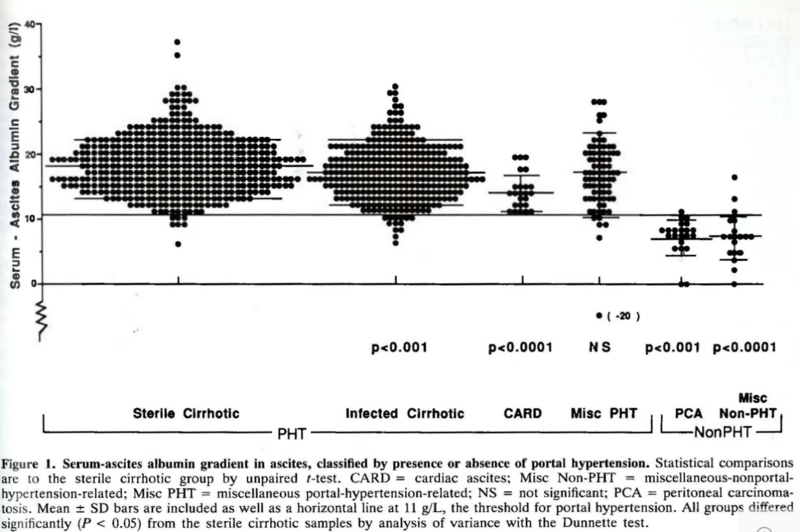

Although most of ascites in the Western world is related to underlying cirrhosis, other potential etiologies need to be considered, including heart failure, malignancy, and tuberculosis. When evaluating for etiology, the serum albumin ascites gradient helps narrow down the list. This is calculated by subtracting the ascites albumin concentration from the serum albumin. A serum albumin ascites gradient (SAAG) ≥1.1 g/dL highly suggests portal hypertension, whereas a SAAG <1.1 g/dL suggests an alternate etiology. Should the SAAG be ≥1.1 g/dL, this can identify liver related portal-hypertensive ascites with an accuracy of approximately 97%.

Prior to the SAAG, there was an exudate-transudate concept applied to the classification of ascites called the ascitic fluid total protein concentration (AFTP). In 1992, Runyon et al compared this older concept to the SAAG calculation in a prospective study of patients with ascites. A total of 901 paired serum and ascitic fluid samples were collected from patients with all forms of ascites. AFTP only classified the cause of the ascites about 56% of the time, thus, it was suggested that SAAG be used instead.

Once you have the SAAG, a total ascitic protein <2.5 g/dL suggests cirrhosis as the etiology for the fluid. By contrast, if your total ascitic protein is ≥2.5 g/dL, consider cardiac ascites. In 1988, Dr. Runyon measured 20 samples of ascites from patients with cirrhosis and 20 samples from patients with heart failure and compared their characteristics. What he found was that both groups had a SAAG ≥ 1.1, but the total ascitic protein concentration was ≥2.5 in all patients with cardiac ascites.

In patients with heart failure–related ascites, the hepatic sinusoids remain structurally normal and lack the collagen deposition seen in cirrhosis. Because of this difference in pathophysiology, an ascitic fluid protein concentration above 2.5 g/dL can be helpful. Still, some overlap exists—Dr. Runyon’s study showed that about 10% of patients with cirrhosis also had high ascitic protein levels, leading to potential misclassification. In these cases, a blood-based marker used in heart failure such as B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) can be particularly useful. A serum BNP cutoff ≥364 pg/mL has demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy to SAAG or total protein in distinguishing cardiac from non-cardiac ascites, with a sensitivity of 98% and specificity of 99%. By pairing traditional fluid analyses and serum BNP, the process of identifying the correct etiology for ascites can be further enhanced and streamlined—especially when there may be a mixed picture.

Once cirrhosis-related portal hypertension is confirmed as the etiology of your patient’s ascites, it is important to check for infection. Together, both the polymorphonucleated (PMN) cell count and fluid culture can be used to diagnose SBP. In the literature, a PMN count of ≥250 cells/uL consistently carries a high likelihood of SBP, and antibiotic therapy is recommended in these scenarios.

While PMN ≥250 cells/uL is nearly diagnostic of SBP, a culture with a causative organism helps tailor antibiotic therapy. At the time of paracentesis, at least 10 mL of ascitic fluid should be inoculated into blood culture bottles to maximize yield. Rising patterns of antibiotic resistance make targeted antibiotic therapy crucial. A PMN count < 250 cells/uL significantly lowers the chances of SBP (summary LR 0.20; 95% CI, 0.11-0.37), and even in cases with a positive bacteriological culture, should not warrant antibiotics. In the absence of other signs of infection, this could represent a contaminant and can self-resolve. In these scenarios, a repeat paracentesis should be completed to evaluate for resolution or progression to SBP.

For visual learners, see LFN’s Quick Tips: Ascites for a great infographic on how to diagnose and manage ascites.

Why is a diagnostic paracentesis still needed if the ascites is established?

Guidelines suggest that a diagnostic paracentesis should be performed on every patient with cirrhosis and ascites who is admitted non-electively. This includes reasons largely unrelated to the liver (e.g., a femur fracture, cellulitis, etc). Much of this stems from the fact that the presentation of SBP can be variable, with some presenting solely with encephalopathy, acute kidney injury, or no symptoms at all.

In 1983, Pinzello et al prospectively performed a paracentesis on 224 consecutive inpatients with ascites and cirrhosis. Twenty-seven (12%) patients had met criteria for SBP by culture and PMN count. Of these patients, 9 (4%) were asymptomatic. Across the literature, the number of asymptomatic patients with SBP has been proposed to be even higher—further emphasizing how crucial a paracentesis is in these patients.

Why does timing matter for a paracentesis? How quickly does it need to be done?

Diagnostic paracentesis offers a clear mortality benefit in those hospitalized with cirrhosis-related ascites when performed early, ideally within 12 hours of hospital admission. The earlier, the better.

In 2014, two larger studies were able to demonstrate the benefits of paracentesis in admitted patients with ascites. In one study pulling from a large nationwide database, Orman et al found that paracentesis reduced mortality by 24% in patients who had a primary admitting diagnosis of ascites or hepatic encephalopathy. Interestingly, self-pay and hospital teaching status were independently associated with a higher likelihood of getting the procedure done at all. In this cohort of patients, in-hospital mortality was reduced in patients that received an early paracentesis (within 24 hours), however this was not statistically significant after adjusting for confounders. An excellent summary of this study can be found in our Evidence Corner.

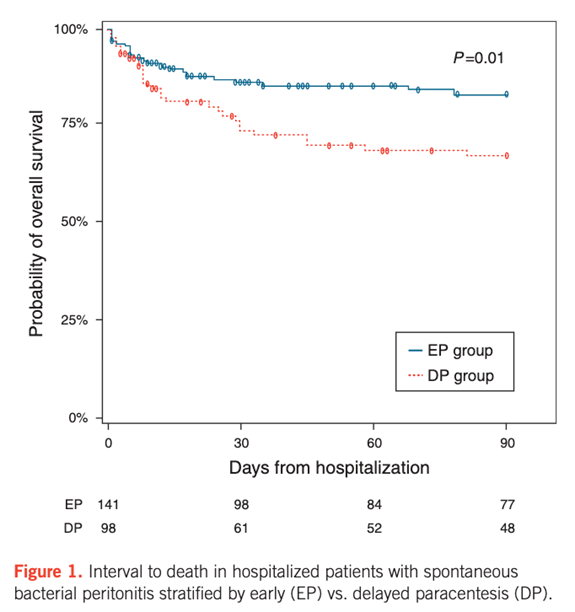

In another study, Kim et al demonstrated that hospitalized patients with SBP who received a delayed paracentesis (12-48 hours after hospital admission) specifically had a 2.7- fold increased mortality risk. In a group of 239 patients with SBP, those who had an early paracentesis <12 hours from admission had lower in-hospital mortality, shorter intensive care days, and a lower 3-month mortality compared to those who had a delayed procedure.

Several retrospective studies have confirmed this. It has been suggested that this observed mortality benefit has several mechanisms. In addition to allowing for early detection of SBP, early paracentesis allows for prevention of kidney injury, which has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality in patients with SBP. Additionally, early recognition of SBP prompts the usage of albumin, which has been shown to decrease mortality incidence among those with cirrhosis and SBP.

Should a diagnostic paracentesis ever be repeated in the same admission?

Patients diagnosed with SBP should be started on IV antibiotics. Traditionally, third generation cephalosporins are recommended as first line antibiotics. In patients that have an organism isolated and are improving clinically on tailored antibiotics, repeat paracentesis may not be warranted. However, more recently, it has been recognized that there are a growing number of infections with multi-drug resistant organisms, where cephalosporins are less effective. As a result, guidelines suggest that a diagnostic paracentesis be performed 48 hours after initiating antibiotic therapy to assess response. A negative response can be defined as a decrease in PMN count <25% from baseline, and this should prompt a broadening of antibiotic therapy.

How are we doing?

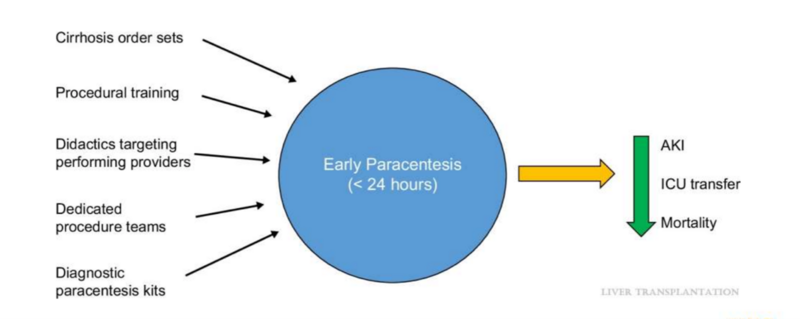

In a large multicenter retrospective study, authors Rosenblatt et al examined the performance of early paracentesis (within 24 hours of admission) among patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Secondary outcomes included inpatient mortality, SBP-related mortality, and 30-day readmission. They found that only 57.6% of patients had their paracentesis done within the first 24 hours. Patients that had concomitant hepatic encephalopathy or acute kidney injury present on admission had even lower rates of early paracentesis. Inpatient all-cause mortality, SBP-related mortality, and 30- day readmission rates were lower among those who had an early paracentesis, further supporting increased adherence to an earlier procedure.

The authors speculated a few barriers. First, it is possible that many clinicians who administer empiric antibiotics may be falsely reassured when patients improve, and a paracentesis may no longer be deemed necessary. Second, with fewer internal medicine residents being required to achieve competency in the procedure, many paracenteses may be delayed until a qualified individual may be available. This can be particularly true on weekends, when limited staff trained in paracentesis may be present.

In a letter to the editor, Giustini et al described similar barriers after surveying providers within the veterans health administration. Based on survey responses, a few potential strategies for improvement were proposed—including more education, standardized order sets, and increased availability of paracentesis kits.

What strategies have been tried so far?

Some efforts in quality improvement have focused on members of the admitting team—with educational programs and best practice advisories. These interventions have successfully improved the number of early paracenteses performed.

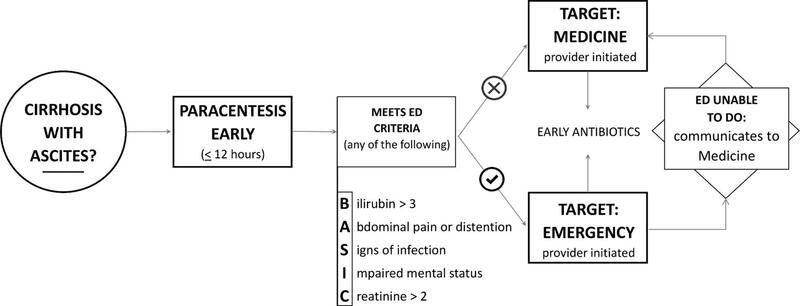

Other interventions have focused on the emergency department, targeting the providers who are in the first phase of care for most admitted patients. Jesudian et al completed a quality improvement study involving an intervention in raising awareness in the emergency department. At their institution, paracenteses were not always possible due to time constraints and competing demands. As a result, their study team developed criteria to help prioritize patients for early paracentesis. They found this multidisciplinary intervention increased the proportion of patients with cirrhosis and ascites who underwent paracentesis in the first 12 hours of presentation—even prior to admission.

Improvement is possible—early paracentesis should be a shared priority across every step of the admission process. By committing to this standard, we can translate evidence into everyday practice and meaningfully improve patient outcomes.

Key Points

- Perform a diagnostic paracentesis on all patients with cirrhosis and ascites admitted non-electively — even if the reason for admission is unrelated to liver disease.

- New ascites? Always confirm etiology (SAAG ≥1.1 → portal hypertension; <1.1 → alternate cause).

- Established ascites? Rule out SBP — up to one-third of cases are asymptomatic.

- Early matters: Paracentesis within 12 hours of admission is associated with lower mortality, fewer ICU days, and improved 3-month survival.

- Repeat paracentesis: Consider at 48 hours if patient not improving, PMN count < 25% from baseline suggests an inadequate response (resistant organisms possible).

- Quality improvement is needed: Less than 60% of patients receive early paracentesis — highlighting opportunities for systems-based change.