Why do we care about hepatic artery thrombosis in liver transplantation?

Introduction:

Hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) is one of the most feared complications in liver transplantation. HAT is associated with ischemic cholangiopathy, biliary abscesses and sepsis, graft loss and need for re-transplantation, and death. HAT can be classified as either early, within thirty days or up to two months of liver transplant, or late HAT, which is beyond this time period. The temporal relationship in early versus late HAT is important as there are significant differences in risk factors, clinical presentation, therapeutic options, and outcomes. The overall incidence of HAT is variable but has been observed in prior studies to be 5%, with a higher incidence in pediatric patients who receive more split grafts from deceased and living donors. HAT is the most common vascular complication following liver transplantation with a mortality rate as high as 50% in early HAT. It is important to note that early HAT is one of the most common causes of early graft loss in liver transplant. This post aims to summarize the pathophysiological changes and risks associated with HAT, review its complications, and current treatment strategies.

HAT pathophysiology and risk factors:

Early HAT develops due to an occlusion of the hepatic artery, which is the sole arterial blood supply to the biliary system. This vascular insult leads to bile duct ischemia, necrosis, biliary abscesses, and ultimately sepsis with risk of death. The exact pathophysiology of HAT is not clear. Although early HAT is predominantly related to technical challenges during surgery and peri-operative factors, ischemic and immunologic risk factors play a role in the development of both early and late HAT.

Table 1. Risk factors associated with HAT.

| Operative risk factors | Non-surgical risk factors |

| Surgical technique | Donor age > 60 years |

| Use of arterial conduits | ABO incompatibility |

| Retransplantation | CMV infection or CMV positive donor |

| Prolonged operation time | Prolonged cold ischemia time |

| Small vessel size | Hypercoagulable recipient |

| Vessel kinking | Recipient cigarette smoking |

| Anastomotic stenosis | Rejection episodes |

| Intimal dissection | Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

Hypercoagulability after liver transplantation:

In the early post-operative period, there is a re-balancing of the pro-coagulation and anti-coagulation factors, and multiple mechanisms lead to a hypercoagulable state in the immediate post-transplant setting. Post-operative factors including substantial surgical damage, stasis resulting from operative clamping of major vessels, and length of surgery increase the risk of developing a hypercoagulable state. Graft quality and graft preservation techniques have also been implicated in this as well. Platelet activation and aggregation result in thromboxane development and fibrinogen activation, which subsequently predispose to arterial thrombosis and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Further, arterial collateral supply to the biliary system from the hepatic artery is absent early after liver transplant, making the graft more susceptible to ischemic injury.

Table 2. Risk factors for development of a hypercoagulable state after liver transplant adapted from Algarni et al.

| Endogenous | Acquired |

| Substantial surgical damage | Donor with factor V Leiden mutation |

| Stasis from clamping major vessels | Infections |

| Release of activators from the donor liver | Viral infections (i.e. CMV) |

| Systemic inflammatory response |

Perioperative hemostatic agent Fresh frozen plasma Platelets Recombinant factor VIIa |

| Graft quality |

Anti-fibrinolytics Aprotinin Aminocaproic Acid |

| Length of surgery | |

| Graft preservation technique | |

| Cold ischemia/reperfusion effect |

Clinical presentation:

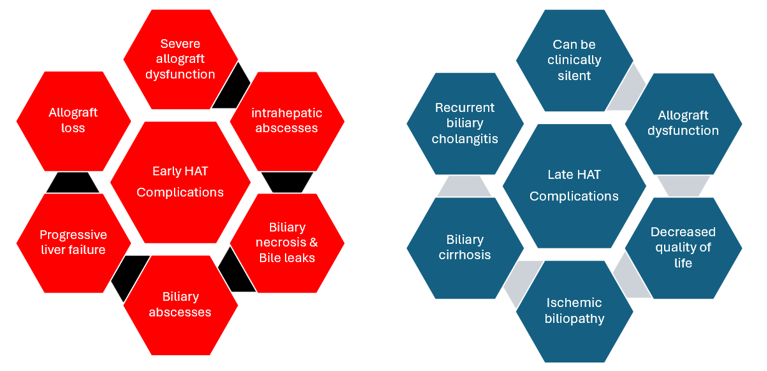

The clinical presentation of HAT is widely variable and can be impacted by both time of onset and development of collateral arterial circulation. Most early HAT cases present within five days with a median time to reported diagnosis of 6.9 days post-transplant; compared to a median of 6 months in late HAT. In both forms, ischemia to the biliary tree drives the disease. The early HAT presentation can be dramatic, acute, and have severe complications if not urgently diagnosed and treated. It can present with acute liver failure with an incidence of 4.9% of cases. HAT can also present with fevers, abdominal pain, leukocytosis, and significant elevations of transaminases consistent with bile leak and intrahepatic abscesses.

In contrast to early HAT, late HAT can have a variable presentation across a clinical spectrum ranging from clinically silent or abnormal serum transaminases to severe biliary complications and recurrent sepsis. Its presentation can be more insidious than that of early HAT and as a result its diagnosis can be missed or delayed. Ischemic cholangiopathy in late HAT can lead to diffuse structuring and dilation of the biliary tree with or without intrahepatic abscesses, and ultimately graft dysfunction and failure.

Figure 1: Complications of early & late HAT

Prophylactic therapy:

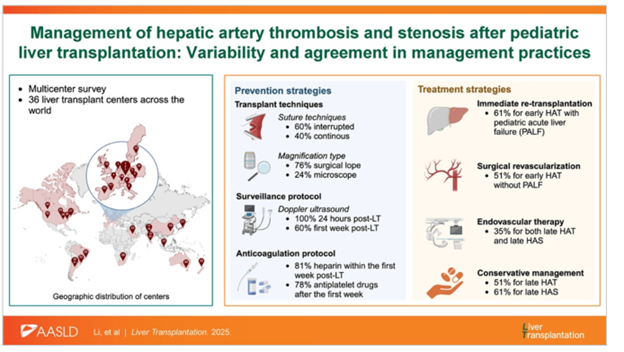

While many centers have instituted prophylaxis regimens for HAT, there is significant heterogeneity in prior studies, which to date have been mostly retrospective and observational in evaluating antiplatelet medications for the prevention of HAT. Four prior studies by Vivarelli et al., Wolf et al., Shay et al., and Oberkofler et al. have evaluated the effect on antiplatelet medications on the development of HAT and demonstrated that time of initiation and dose of antiplatelet varied across transplant programs. Only one of these studies assessed the incidence of both early and late HAT in patients on antiplatelet medications compared to a control population. In a recent systematic review with expert panel of recommendations, aspirin was defined as the only method of thromboprophylaxis that lowered the incidence of HAT in liver transplant recipients overall, and notably in those with higher rates of HAT such as complex arterial reconstruction with aortic conduits. However, this recommendation was made with low-quality evidence and small size effect. Other medications studied in deceased donor liver transplant (DDLT) recipients include PGI2 analogs and vitamin K antagonists, but neither have shown an impact on HAT incidence. In LDLT recipients, post-operative anti-thrombotic protocols have demonstrated higher bleeding complications without reduction in HAT. Among pediatric liver transplant centers, there is variability in use of prevention strategies and treatment strategies for HAT mirroring adult transplant centers. The current data highlight an important opportunity for research aimed at improving transplant management and preventing hepatic artery thrombosis.

Diagnosis of HAT:

The initial diagnostic test of choice is color duplex ultrasound (US). US is fast, non-invasive, avoids radiation exposure, and assesses graft parenchyma and vasculature including the hepatic artery anastomosis. Serum biochemical testing is also performed post-transplant, and abnormal liver enzymes or liver function based on this testing should prompt further workup with US. In cases where there is suspicion of HAT or an abnormal US, either computed tomography-angiography, laparotomy, or conventional angiography are performed for confirmation. Conventional hepatic arterial angiography is considered the gold standard in clinical practice to diagnosis HAT. Magnetic resonance imaging has also been used in the diagnosis of HAT, although it is less readily available than CT and more time-consuming to perform. While the presentation of late HAT can be more variable than early HAT, diagnostic evaluation is similar to early HAT.

Given the spectrum of presentations in early HAT, some transplant centers also utilize US in screening protocols. This strategy employs the use of US and serial biochemical testing in varied intervals post-operatively to detect HAT before its deleterious sequelae become clinically evident. While many transplant centers have their own protocols for screening and diagnosis, the frequency and interval of testing done by centers who have published their protocols are variable. Screening for HAT is crucial due to its variable clinical presentations and the importance of timely management.

Treatment of Early HAT:

Revascularization:

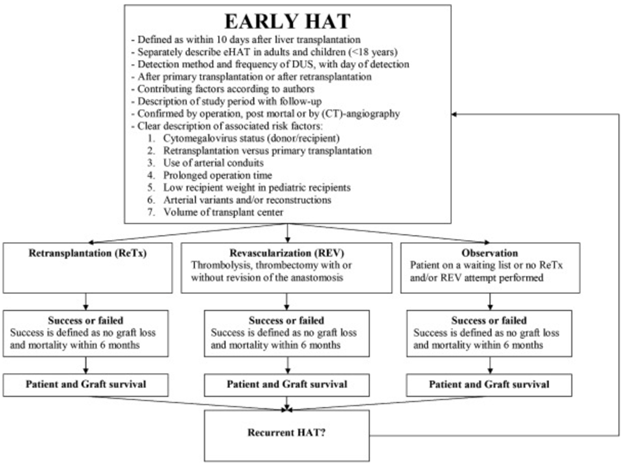

The cornerstone of early HAT treatment includes urgent revascularization and retransplantation if this is not successful. Recently published practice guidelines by the AASLD and AST recommend that hepatic artery complications should be managed urgently to avoid graft loss with the use of surgical/percutaneous endovascular intervention or anticoagulation.

There are a variety of revascularization techniques that have been described including endovascular thrombolysis, open thrombectomy with revision of the surgical anastomosis and aorta-hepatic conduit interposition. When endovascular techniques are applied, mechanical thrombectomy followed by thrombolysis or thrombolysis alone can be performed. It has been previously demonstrated that thrombolysis in this setting is effective and safe, but does carry a risk of intra-abdominal hemorrhage, specifically within the first seven days after transplant. Surgical revascularization strategy is an accepted strategy that has been shown to have survival outcomes no different from individuals without HAT in one single center study, with high technique success rate. Choice of intervention between endovascular and surgical revascularization will in part depend on a specific transplant center’s level of expertise and institutional preferences. To date there are no long-term randomized control trials comparing these two options.

Retransplantation

Retransplantation should be considered if there is severe allograft injury or failure, or if very early in the post-transplant course. While retransplantation of the liver is considered the most definitive therapy, it historically has been controversial which treatment modality is the most effective. Despite this, repeat liver transplantation is required in early HAT in up to 50-60% of cases and more frequently performed in pediatric patients. Liver transplantation is an accepted treatment for early HAT and patients can receive MELD exception points from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). Individuals with early HAT within seven days of liver transplantation with severe graft dysfunction, defined as an AST of >3,000 with at least an INR >2.5, ABG pH <7.3, VBG pH of <7.25, or lactate >4 qualify for status 1a listing for liver transplant. HAT occurring within fourteen days of liver transplant that do not meet the criteria for 1a listed may be granted an automatic MELD exception of 40 points.

Conservative management and monitoring can be considered in select cases but is not common nor the standard of care in clinical practice due to the severity and potential catastrophic consequences of early HAT.

Figure 2: Proposed management strategies of early HAT proposed by Bekker et al. in 2009

Treatment of Late HAT:

Treatment strategies for late HAT are overall similar to that of early HAT. Conservative management and/or endovascular thrombolysis can be recommended. If the onset is gradual, then adequate collateralization may develop to permit graft survival without endovascular intervention. Conservative management in late HAT varies based on the clinical presentation, but can include surveillance or long-term antibiotics use for cholangitis. Liver abscesses may require treatment with antibiotics, drainage, or partial hepatectomy. Although late HAT has been reported to have less morbidity than early HAT, surgical treatments including surgical thrombectomy, recombinant plasminogen lysis with hepaticojejunostomy, or retransplantation may be necessary. Late HAT does not qualify for prioritized liver transplant listing nor MELD exception points, however patients with atypical and severe complications may be considered for nonstandard MELD exceptions points on an individualized basis through a narrative request to the National Liver Review Board. According to UNOS, the requirements for MELD exception points are: two or more episodes of cholangitis requiring hospital admission over a three-month period and biliary strictures not responsive to stenting/dilations or bacteremia with highly resistant organisms.

Figure 3. Summary of prophylactic management and treatment strategies for hepatic artery thrombosis and hepatic artery stenosis from Li et al. in a pediatric population.

Key points:

-Hepatic artery thrombosis is the most feared vascular complication of liver transplant which can cause severe cholangitis, abscesses, allograft dysfunction, failure, or death

-The clinical presentation of early compared to late HAT can vary, but the initial diagnostic test of choice is a color duplex ultrasound followed by angiography

-Treatment of HAT can include surgical or percutaneous endovascular intervention, anticoagulation. Retransplantation is often performed if HAT is diagnosed early, and certain patients will qualify for MELD exception points.

-Aspirin is the most common choice of prophylaxis, but the ideal initiation, dose, and length of therapy remains unclear, and varies across different transplant centers