When Medicine Turns Toxic: The Hepatotoxic Potential of Common Drugs

Learning Objectives:

- Define drug-induced liver injury and classify it based on clinical presentation and liver enzymes.

- Identify hepatotoxic effects of medications using available resources.

- Describe the general diagnostic and treatment approach for drug-induced liver injury and review prognostic factors.

What is Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI)?

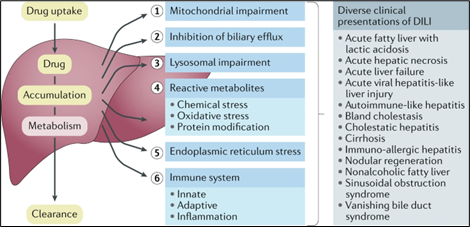

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) refers to liver injury caused by ingestion of prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, herbal products, or dietary supplements. Cellular damage in DILI can reflect toxic effects of the culprit medication or its metabolites, or immune-mediated effects (Figure 1). The annual incidence of DILI in the general population is approximately 15--20 per 100,000 people, although this may be an underestimate. Most cases are asymptomatic and therefore unreported. When present, clinical symptoms are often nonspecific and may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and jaundice. DILI can also present with acute liver failure; acetaminophen is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the U.S.

Figure 1. Cellular mechanisms contributing to DILI and clinical presentations (from Weaver et al., 2020)

The Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) is an NIH-sponsored research program that studies cases of severe DILI. Suspected cases can also be reported to the Food and Drug Administration for further evaluation.

How is DILI classified?

The first step in decoding DILI is to classify the pattern of liver injury:

- Hepatocellular injury is characterized by marked elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST), usually three times or more above the upper limit of normal (ULN).

- Cholestatic injury presents with disproportionate elevation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP).

- Mixed injury involves elevations in both aminotransferases and ALP.

The R factor, calculated as (ALT ÷ ULN) ÷ (ALP ÷ ULN), is used to distinguish among these patterns. Note that a single medication may produce different patterns of enzyme elevation in different patients, and enzyme profiles can shift over time.

Another distinction is between non-immune mediated and immune-mediated DILI. The former may take months to emerge and typically lacks systemic symptoms. In contrast, immune-mediated DILI can present with symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction (fever, rash, eosinophilia) with a shorter onset.

What medications cause DILI?

A wide variety of prescription medications, over-the-counter drugs, and herbal or dietary supplements have been implicated in DILI. The LiverTox database catalogs more than 1,000 agents with reported hepatotoxicity and serves as a valuable resource for physicians. Among prescription medications, antimicrobials are frequently implicated (Figure 2). A list of common medications linked to DILI is shown in Table 1, along with presenting patterns of liver injury, symptoms, and key management considerations.

| Spanish Registry (n = 843) | DILIN (n = 899) | Icelandic study (n = 96) |

| Amoxicillin‐clavulanate (22%) | Amoxicillin‐clavulanate (10%) | Amoxicillin‐clavulanate (22%) |

| Anti‐tuberculosis (4.5%) | Isoniazid (5.3%) | Diclofenac (6.3%) |

| Ibuprofen (3%) | Nitrofurantoin (4.7%) | Nitrofurantoin (4%) |

| Flutamide (2.6%) | Bactrim (3.4%) | Azathioprine (4%) |

| Atorvastatin (1.9%) | Minocycline (3.1%) | Infliximab (4%) |

| Diclofenac (1.8%) | Cefazolin (2.2%) | Isotretinoin (3%) |

| Ticlopidine (1.4%) | Azithromycin (2%) | Atorvastatin (2%) |

| Azathioprine (1.3%) | Ciprofloxacin (1.8%) | Doxycycline (2%) |

| Fluvastatin (1.3%) | Levofloxacin (1.4%) | Imatinib (1%) |

| Simvastatin (1.3%) | Diclofenac (1.3%) | Isoniazid (1%) |

| HDS (3.4%) | HDS (16.1%) | HDS (16%) |

Figure 2. Most common medications causing DILI from three prospective studies (Hayashi et al. 2017, Chalasani et al. 2015, Björnsson et al. 2013)

Table 1. Review of common medications linked to DILI (information from LiverTox).

| Agent / Class | Pattern of Liver Injury | Typical Presentation / Latency | Key Points / Management |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) | Cholestatic (sometimes mixed or hepatocellular) | Typically appears after antibiotic completion (up to 8 weeks); patients often have jaundice | Injury is due to clavulanate, not amoxicillin; amoxicillin alone is safe; effects are usually self-limited |

| Isoniazid | Hepatocellular | Often presents with transient, asymptomatic aminotransferase elevation that resolves with continued therapy; severe cases show hepatitis symptoms and ALT > 10x ULN | Monitor liver tests; stop drug if symptoms of hepatitis appear; continuation may be possible with mild liver enzyme elevation |

| Methotrexate | Hepatocellular; chronic use → fatty liver, fibrosis, cirrhosis | Mild, self-limited liver enzyme elevations; chronic use may lead to chronic liver disease, especially with metabolic risk factors | Routine hepatic panel monitoring; annual liver elastography if risk factors or high cumulative doses; metabolic risk factors are often main cause of chronic liver disease, rather than methotrexate itself |

| Statins | Hepatocellular, sometimes cholestatic | Variable latency (weeks to years); mostly asymptomatic, transient enzyme elevation | Baseline hepatic panel only; routine monitoring not required; safe in chronic liver disease; discontinue if ALT/AST >3x ULN with symptoms or a rise in bilirubin |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | Hepatocellular (sometimes mixed or cholestatic) | Many develop asymptomatic injury early in treatment; labs checked before each cycle | Withhold therapy if grade 2 injury (ALT 3–5x ULN, bilirubin 1.5–3x ULN) and consider steroids; permanently discontinue for higher injury grades |

| Herbal and Dietary Supplements (HDS) | Variable | ≈16% of DILI cases; bodybuilding supplements are the most common HDS leading to DILI; they present with prolonged jaundice in young, healthy men | Obtain full supplement history; patients often under-report use |

What is the diagnostic workup?

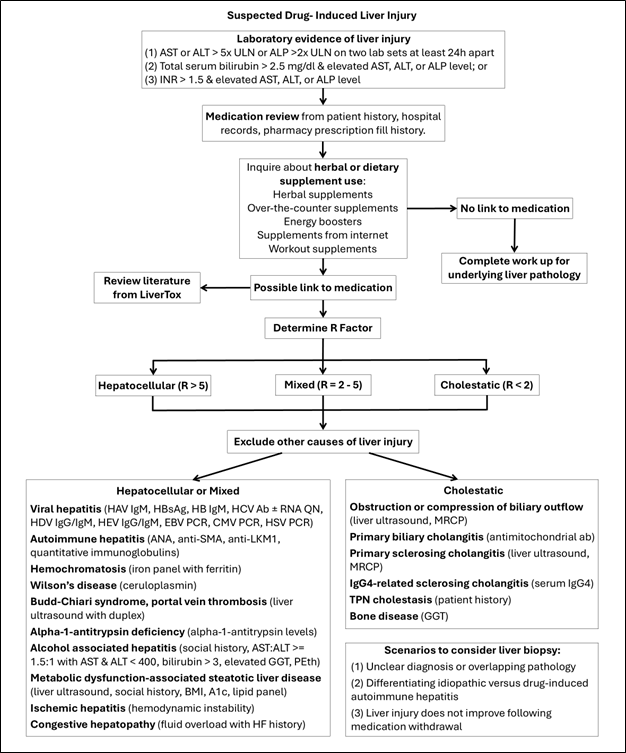

Diagnosis of DILI requires careful clinical evaluation, as no specific biomarkers or histological features exist. Key steps include:

- Recognizing a recent and persistent change in liver biochemistries significant enough to suggest liver injury.

- Establishing a temporal association between drug exposure and the onset of liver test abnormalities through patient history and review of prescription-fill records.

- Assessing the hepatotoxic potential of the suspected agent using available resources such as LiverTox. The RECAM score, a revised version of RUCAM, can also aid in assessing the likelihood of DILI.

- The medication may not appear on the active medication list and may require detailed review in collaboration with a pharmacist.

- Determining biochemical pattern of liver injury (hepatocellular, cholestatic, mixed) by calculating the R factor, while systematically ruling out alternative etiologies of liver disease (Figure 3).

Improvement in liver enzymes following withdrawal of the offending drug supports the diagnosis. Although liver biopsy is not routinely required, it may be useful in diagnostically uncertain cases. These scenarios include differentiating idiopathic versus drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis (DI-AIH), cases with overlapping features of another liver pathology, or cases in which liver injury does not improve following medication withdrawal, suggesting an alternate diagnosis or delayed improvement.

Figure 3. Approach to DILI diagnosis

How is DILI treated and managed?

Management of DILI depends on identification of the underlying cause. In acetaminophen-induced liver injury, early administration of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) replenishes glutathione and mitigates hepatocellular damage. Patients are initially treated with a high loading dose, then a maintenance dose over several days. If administered within 12 hours of acute ingestion, there is a high likelihood of preventing liver injury. NAC may also improve transplant-free survival in acute liver failure not related to acetaminophen. A three-day course of NAC has shown benefit in adults patients with non-acetaminophen-related DILI leading to acute liver failure, with improved transplant-free survival. Check out this LFN ‘Clinical Pearls’ article for more on NAC!

In most cases of DILI, discontinuation of the offending agent leads to resolution of liver injury (>90% of cases). Supportive care during the drug-withdrawal period includes fluids, antiemetics, and antipruritic agents. Ursodeoxycholic acid can be used for antipruritic symptoms and may possibly promote DILI recovery, especially if there is cholestasis. The culprit medication should be recorded as an allergy to avoid re-exposure, except when the benefits outweigh the risks in life-threatening situations.

For DI-AIH or severe hepatitis related to immunotherapy, treatment consists of a 1–3-month course of corticosteroids with a taper. Patients with idiosyncratic DILI with severe hypersensitivity or DRESS syndrome, may also benefit from corticosteroids (generally 1mg/kg of methylprednisolone). There is no definitive guidance on optimal duration and dosing, given lack of research. Check out this LFN ‘Clinical Pearls’ article for more on DI-AIH vs DILI!

Severe cases of DILI may lead to chronic liver injury or acute liver failure with coagulopathy (INR > 1.5) and encephalopathy (altered mental status/asterixis). Patients with acute liver failure should be promptly transferred to a transplant center for evaluation of liver transplantation since chances of self-recovery are low (~25%). Prognosis is influenced by the pattern of liver injury, biochemical severity, and underlying liver pathology. Poor prognostic factors include high bilirubin and INR, low serum albumin, and pre-existing liver disease. Patients with hepatocellular DILI and hyperbilirubinemia (ALT/AST ≥ 3x ULN, ALP < 2x ULN, total bilirubin ≥ 2x ULN) have the highest mortality risk (Hy’s law). Cholestatic injury is more likely to develop chronic liver injury, whereas mixed-pattern injury generally confers the most favorable prognosis.

Take Home Points:

- Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) refers to elevated liver tests that result from exposure to a medication, herbal compound, or dietary supplement.

- Biochemical patterns of injury are categorized according to the predominant enzyme elevation.

- A detailed history is crucial, as latency between exposure and enzyme elevation may span months.

- Patients with hepatocellular DILI accompanied by hyperbilirubinemia are at the highest risk of mortality (Hy’s law).

Written by: Ana Untaroiu, M.D. University of Louisville

Post reviewed by Vinay Jahagirdar (Fellow Lead), Bilal Khalid (Faculty Editor)