Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Management Tips and Tricks

What is PSC?

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is defined as a cholangiopathy with chronic fibroinflammatory damage of the biliary tree seen on pathology from liver biopsy. PSC is felt to be an autoimmune process, although unlike primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) or autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), there are no known autoantibodies yet identified. PSC can occur at any age, with peak incidence around 40 years of age, and is more common in men than women (generally 2:1 proportion). PSC also frequently co-exists with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD); population-based epidemiology studies have found that ~68% of patients diagnosed with PSC also carry a diagnosis of IBD, with the majority of these being diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC). Over time, PSC leads to periductular fibrosis of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts which eventually result in strictures, further complicated by bacterial cholangitis and decompensated liver disease.

Although the pathophysiology of PSC is not yet elucidated, several hypothesized mechanisms exist. These include autoantibodies, genetic mechanisms, dysbiosis of the gut flora, T-cell mediated dysfunction, and more.

Why is PSC important?

The incidence of PSC in the United States is 1-1.5 cases per 100,000 patients and the prevalence is estimated 6-16 per 100,000 patients. Although relatively rare, PSC has significant morbidity and mortality associated with it, as well as several comorbid conditions with which it is associated. Most patients diagnosed with PSC develop slowly progressive liver disease that eventually results in cirrhosis. The median time to death or liver transplantation (LT) has been found to be between 9 to 21 years.

Other complications of PSC include bacterial cholangitis, biliary strictures, and malignancies (i.e., cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer, colorectal cancer). Bacterial cholangitis is the most common complication, with up to 38% of patients with PSC prior to LT developing an episode of bacterial cholangitis. Outside of short-term risks of bacterial cholangitis and needing hospitalization, antibiotics, and possible invasive interventions, there is also a long-term risk of malignancy. Patients with PSC have up to a 400 times greater risk for cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) compared to the general population, with the highest risk of CCA diagnosis in the first year after PSC diagnosis. The risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) is up to 12 times greater in patients with PSC as compared to the general population, and patients with PSC-IBD are at higher risk for CRC than those with IBD alone.

In a long-term follow-up population-level study of patients with PSC, the annual mean work productivity loss was 25%, demonstrating the significant financial and economic impact of PSC.

When should I suspect PSC and how do I come to the diagnosis?

PSC should be suspected in patients of any age with evidence of cholestatic liver injury. That is, elevated serum levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), or bilirubin. Patients can be with or without symptoms at the time of diagnosis (the most common symptoms being fatigue, abdominal pain, pruritus, fever). Given PSC has no known exact mechanism or elucidated pathophysiology, the diagnosis is only made once other etiologies of cholestatic liver injury are ruled out and with the presence of characteristic imaging findings.

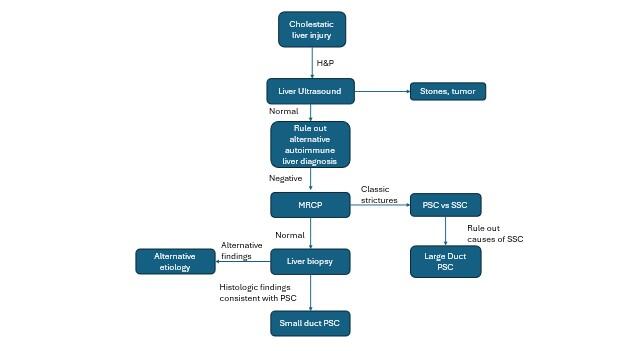

Figure 1. Diagnostic algorithm for PSC, adapted from EASL and AASLD PSC guidelines (5, 10).

A key part of the diagnostic algorithm is imaging. Although ultrasound is often used in practice as the first diagnostic imaging technique in a work-up of cholestasis, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the imaging technique of choice in diagnosing PSC. In PSC, MRCP will show characteristic diffuse, intrahepatic strictures alternating with normal or dilated segments of bile ducts. The development of MRCP has obviated the need for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the diagnosis of PSC. In fact, EASL and AASLD guidelines recommend avoiding ERCP for the diagnosis of PSC (it can, however, be useful in management of prominent strictures, as will be discussed below).

Furthermore, because of imaging advances, liver biopsy is no longer needed for diagnosis if there are characteristic imaging findings on MRCP. Given the procedural risks of liver biopsy, it is now reserved for cases with diagnostic uncertainty.

Finally, if there are imaging findings characteristic of PSC on MRCP, etiologies of secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC) must be first ruled out prior to making a diagnosis of PSC. Please see the excellent LFN post on SSC here and how to evaluate for the various etiologies.

Back to the case:

The patient underwent MRCP which demonstrated numerous intrahepatic strictures with intermittent dilated segments of intrahepatic bile ducts. There was no extrahepatic biliary ductal dilation or high-grade stricture. IgG4 was normal, and there were no other concerning history or laboratory findings for secondary sclerosing cholangitis, and he was diagnosed with PSC. He tells you the pruritus is very bothersome and affecting his quality of life. He tells you he has read about ursodiol being used to treat PSC and asks if this will help improve his pruritus.

Managing PSC

Primary Medical Management

Although PSC is a chronic liver disease with significant morbidity as detailed above, no medication or treatment has yet been identified that prevents or reverses disease progression. Historically, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has been prescribed to patients with PSC given some early data that showed improvements in ALP serum levels after 12 months on a low (i.e., 13-15 mg/kg/day) dose of the medication, although no improvement in transplant-free survival. The mechanism by which UDCA works to help improve symptoms and ALP levels in PSC is unclear, but there are several hypothesized mechanisms including increased bile flow, direct and indirect cytoprotection, stabilization of cell membranes, immunomodulation, and dilution of hydrophobic bile acid pool. However, subsequent studies have shown inconsistent results regarding its efficacy in reducing ALP levels or symptom improvement. Furthermore, higher doses of UDCA have been associated with poorer clinical outcomes compared to placebo, including death, need for liver transplant, varices, and development of cirrhosis. The AASLD guidelines on PSC recommend patients who are not eligible or interested in clinical trials can be tried on UDCA 13-23 mg/kg/day if they have persistently elevated ALP but recommend only continuing this medication after 12 months of initiating treatment if there is a meaningful reduction or normalization of ALP or symptoms. However, EASL guidelines do not recommend UDCA given the conflicting evidence. Thus, it is a treatment option to keep in mind for patients with PSC who are not eligible for clinical trials with persistently elevated ALP or symptoms, but who are interested in trialing a medication.

Endoscopic Management

For patients found to have a high-grade stricture on MRCP, ERCP can be used to endoscopically treat these strictures. Endoscopic interventions include balloon dilation, plastic or metal stent placement. Plastic stents must be exchanged every 3 months to prevent occlusion and risk of bacterial cholangitis. Additionally, the presence of a high-grade stricture on MRCP should raise concern for CCA. Thus, AASLD guidelines recommend obtaining intraductal tissue samples during ERCP for high-grade strictures in ERCP.

Pruritus Management

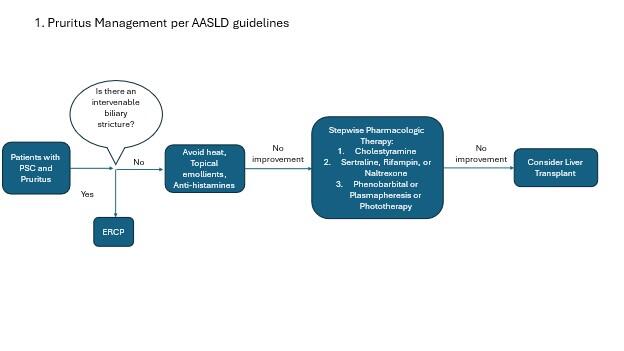

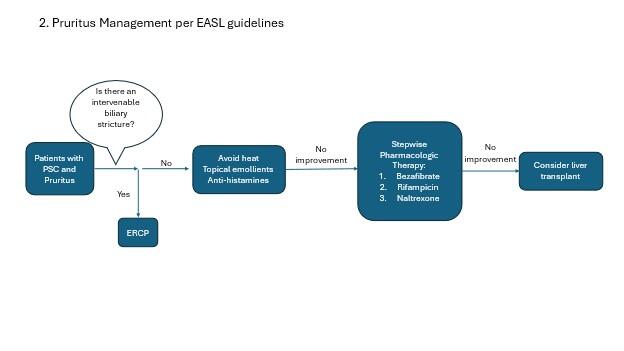

Pruritus remains one of the most challenging management aspects of PSC. Pruritus can be severe and is often associated with poor quality of life in PSC patients. This is partly because we do not have great treatment options. In patients with an obvious, reachable stricture on imaging, endoscopic management of that stricture is recommended. First line medical management includes lifestyle and over the counter management options including heat avoidance, topical emollients, and antihistamines. Per the AASLD guidelines, cholestyramine is recommended as the next line of therapy. However, cholestyramine can be practically challenging due to its binding to other drugs and reducing their absorption. Other medications must be taken 1 hour before, or 4-6 hours after taking cholestyramine, which can make it challenging for planning other medications. For this reason as well as lack of compelling evidence specifically for pruritus in PSC populations, the EASL guidelines do not recommend cholestyramine in their algorithm for pruritus management.

Other therapies include sertraline, rifampin, and naltrexone. EASL guidelines also include bezafibrate as an option, however this medication is not available in the US. Please see the high yield LFN post on management of pruritus in cholestatic liver disease for more information.

Figure 2. Management of pruritus in PSC patients (adapted from AASLD and EASL guidelines).

Liver Transplantation

Given there is no disease-modifying treatment for PSC as discussed above, many will go on to develop decompensated liver disease requiring liver transplantation (LT). Indications for LT in patients with PSC include decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), high grade biliary dysplasia, recurrent bacterial cholangitis, severe pruritus or jaundice. Prognosis after LT in patients with PSC is excellent, generally over 85% five year survival rates.

Back to the case:

You take note of the patient’s family history of IBD. Based on this family history of IBD and his personal diagnosis of PSC, you order him a diagnostic colonoscopy to rule out underlying IBD.

PSC and IBD

PSC is associated with IBD, particularly Ulcerative Colitis (UC). Therefore, AASLD and EASL guidance suggests performing a diagnostic colonoscopy, including terminal ileum intubation with biopsies at time of new diagnosis of PSC, and every 5 years thereafter in patients without IBD. In patients with PSC without IBD, CRC is 5-12 times more likely compared to the general population. Therefore, colonoscopy every 5 years also serves as CRC screening. Finally, the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) is 2-5x higher in patients with IBD and PSC than those with IBD alone. For this reason, patients with PSC-IBD are recommended to undergo annual colonoscopy for colorectal cancer surveillance.

Other Malignancy Surveillance

Patients with PSC are at higher risk of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) and gallbladder malignancy than the average population. For this reason, it is recommended to obtain MRI/MRCP annually in patients with large-duct PSC for CCA and gallbladder malignancy screening. In patients that develop cirrhosis in PSC, the recommended frequency of imaging screening for HCC and CCA/gallbladder cancer increases to every 6 months as is recommended in general for patients with cirrhosis. Alternating MRI/MRCP and US every 6 months in these cases is a reasonable imaging strategy. HCC risk is not notably increased in PSC patients unless they have concurrent cirrhosis.

Patients with PSC are also at increased risk of gallbladder carcinoma compared to the general population. Furthermore, gallbladder polyps are felt to possibly represent a premalignant stage, with increasing size associated with increasing risk of malignancy. Cholecystectomy is recommended for patients with PSC with gallbladder polyps >8mm given risk of malignancy. Gallbladder cancer surveillance is concurrently performed with the recommended annual CCA surveillance MRI/MRCP.

PSC-AIH overlap syndrome

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease of the liver without an apparent cause. Prior studies have estimated between 4 and 10% of patients diagnosed with PSC had PSC-AIH overlap syndrome. Thus, when diagnosing PSC it is important to consider whether there could also be a component of AIH present, as this will change management. AIH should be suspected in patients with a predominantly hepatocellular liver injury (which is not classically seen in PSC alone). Although liver biopsy is not used in textbook cases of PSC, biopsy should be considered in patients with significantly elevated aminotransferases, and characteristic histologic findings of AIH can further support a diagnosis of PSC-AIH overlap syndrome. In a similar vein, in patients diagnosed with AIH and found to have IBD, AIH-PSC overlap syndrome should be considered in those patients with unexplained cholestatic liver abnormalities or poor response to typical steroid therapy.

In patients with evidence of PSC-AIH overlap syndrome per the diagnostic criteria above, treatment with immunosuppression with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive therapies per AIH guidelines is recommended.

Healthcare maintenance

Patients with PSC are at higher risk for protein malnutrition than the average population due to reduced intestinal absorption in the setting of chronic cholestatic liver disease. Thus, bone density examination is recommended at time of diagnosis and every 2 to 3 years thereafter based on risk factors.