A Beginner’s Guide to Liver Transplant Immunosuppression

What is the importance of immunosuppression post liver transplantation?

Liver transplantation is a life-saving therapy for patients with decompensated cirrhosis, acute liver failure, select hepatocellular carcinomas, and other specific indications.

Like other solid organ transplants, the recipient’s immune system can reject the liver, potentially leading to graft dysfunction or failure. Immunosuppressive agents are used to prevent rejection. (Take a look at the excellent Pathology Pearls posts on acute cellular rejection and chronic cellular rejection to learn more after graft rejection!)

While essential for graft survival, immunosuppression carries risks, including infection, metabolic issues, malignancy, and organ-specific toxicities. The ideal regimen balances preventing rejection with minimizing side effects. Achieving this balance—the “art of immunosuppression”—requires individualized decisions based on factors like the transplant indication, comorbidities, and immunosuppression-related side effects.

What are the phases of immunosuppression in liver transplantation?

Immunosuppression in liver transplantation has two phases: induction and maintenance.

During the induction phase, potent immunosuppressive medications (i.e corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors and antimetabolites) are administered, both intraoperatively and in the first 30 days following liver transplantation, to suppress the immune response. In select cases, induction therapies like interleukin-2 receptor antagonists (e.g., basiliximab) may be utilized.

The maintenance phase follows the induction period and continues for the lifetime of the graft. Maintenance immunosuppression protocols generally include a combination of calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites, mTOR inhibitors, and/or corticosteroids. Regimens are individualized based on transplant indication, time since surgery, rejection history, comorbidities, cancer or infection risk, and drug tolerability.

What Medications Are Used for Immunosuppression Following Liver Transplantation?

Corticosteroids

Since the first successful liver transplant in 1967, corticosteroids have been central to induction therapy and managing rejection. They act quickly by inhibiting T-cell activation and cytokine production, reducing the risk of acute cellular rejection. High intravenous doses are given around surgery, then transitioned to oral therapy and tapered off over three to six months unless extended for specific reasons.

Long-term use is avoided due to side effects—infection, metabolic changes, bone loss, psychiatric effects, adrenal suppression, and cataracts. Maintenance regimens therefore rely on steroid-sparing agents like calcineurin inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, and antimetabolites.

Calcineurin Inhibitors (CNIs)

Calcineurin inhibitors, specifically tacrolimus and cyclosporine, are first-line maintenance immunosuppressants in liver transplantation, inhibiting calcineurin to block IL-2 production and T-cell activation. Tacrolimus is ~100 times more potent than cyclosporine and generally preferred due to lower rejection rates, though it carries higher nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity risk.

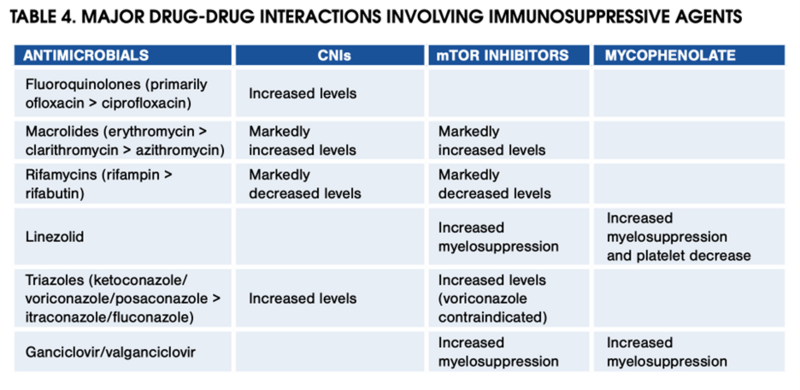

CNIs are started early post-transplant and continued with or without additional immunosuppression agents. Dosing is guided by trough levels, with target levels based on time interval post-transplant and patient-specific factors. CNIs are metabolized via CYP450 and prone to drug interactions. The table below highlights key interactions that clinicians should keep in mind.

Table 4 from the 2012 AASLD/AST Practice Guidance on the Long-term Management of the Successful Adult Liver Transplant

Cyclosporine and tacrolimus share a similar side effect profile—renal dysfunction, metabolic issues (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia), neurotoxicity, and vascular complications. Cyclosporine poses a higher cardiovascular risk, while tacrolimus more often causes hyperglycemia and neurologic effects.

Antimetabolites

Antimetabolite therapies—such as azathioprine (AZA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and mycophenolate sodium (MPS)—are frequently used alongside CNIs for maintenance immunosuppression after liver transplantation. They help reduce CNI exposure and associated toxicity or provide additional immunosuppression in patients with autoimmune liver disease or prior rejection episodes. Mycophenolate is generally preferred over azathioprine due to its superior efficacy in preventing acute cellular rejection.

Both azathioprine and mycophenolate inhibit purine synthesis, suppressing B- and T-cell proliferation. Therapeutic drug monitoring is not required for either agent. However, thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) activity should be assessed before starting azathioprine, as low enzyme activity can increase the risk of severe bone marrow suppression.

Common side effects include bone marrow suppression and hepatotoxicity with azathioprine, and bone marrow suppression plus gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain) with mycophenolate. Transitioning from mycophenolate mofetil to the enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium formulation may help alleviate these gastrointestinal issues.

Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Inhibitors

The mTOR inhibitors, sirolimus and everolimus, suppress the immune system by inhibiting T cell activation and proliferation. Like calcineurin inhibitors, they are metabolized via the cytochrome P450 system and require drug level monitoring.

mTOR inhibitors can be used either alongside or in place of calcineurin inhibitors, to minimize the risk of renal toxicity associated with calcineurin inhibitor therapy. Due to known antiproliferative effects, they are also utilized in patients at high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) recurrence or de novo malignancy post-transplant.

Common side effects include dyslipidemia, impaired wound healing, oral ulcers, proteinuria, fluid retention, pulmonary fibrosis, and bone marrow suppression. Baseline and periodic lipid panels and urine protein-to-creatinine ratios are recommended. Sirolimus carries an FDA black box warning for liver transplant patients due to reports of early hepatic artery thrombosis with mortality and graft loss. Because of this, it is not a preferred agent, especially in the first 30 days after transplant.

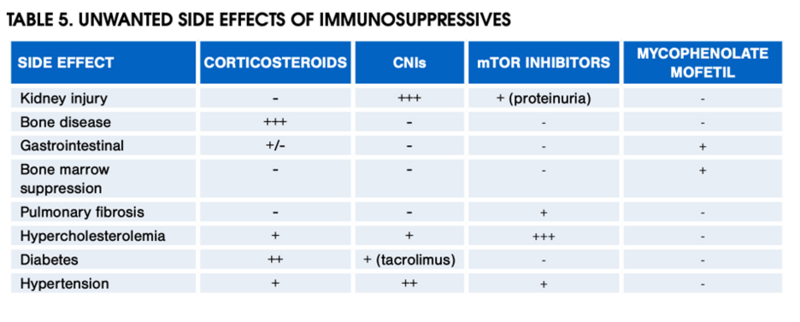

Check out the table below for the side effect profiles of the various maintenance immunosuppression agents discussed thus far.

Table 5 from the 2012 AASLD Practice Guidance on the Long-term Management of the Successful Adult Liver Transplant

Induction Agents: IL-2 Receptor Antibodies

While most liver transplant programs utilize intravenous corticosteroids in addition to calcineurin inhibitors during the induction phase post-transplant, alternative induction agents can be considered. Basiliximab, a humanized IL-2 receptor antibody, selectively inhibits T cell proliferation. Studies (including Best et al 2020 and Bittermann et al 2019) show basiliximab, with or without steroids, reduces mortality, graft failure, and acute rejection and improves renal function at 6 months post-transplant. The 2024 EASL Clinical Practice guidelines provide a strong, consensus recommendation for the use of basiliximab induction with delayed introduction of tacrolimus in patients at risk of developing post-transplant renal dysfunction. Similarly, the 2025 AASLD/AST guidance provides a weak recommendation for the use of basiliximab induction in order to delay introduction of calcineurin inhibitors in patients with pre-existing kidney dysfunction.

What is the standard or typical immunosuppression protocol post liver transplantation?

Immunosuppression protocols vary by center, but most use high-dose corticosteroids plus calcineurin inhibitors, with or without antimetabolites, during induction. In patients with renal dysfunction, basiliximab may be used to delay calcineurin inhibitor initiation. Corticosteroids are typically tapered by 3–6 months post-transplant.

The 2025 AASLD/AST guidance recommends tacrolimus maintenance monotherapy for patients at low risk of rejection, with alternative regimens tailored to patient-specific factors. Target tacrolimus trough levels vary by transplant center and by time since transplantation; therefore, dosing adjustments should follow the specific protocol of the patient’s transplant center. As a general reference, the 2024 EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on Liver Transplantation, provides a strong consensus recommendation for tacrolimus trough targets of 6-10 ng/mL during the first month post-transplant, followed by 4-8 ng/ml thereafter. A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that these lower tacrolimus trough goals in combination with three months of corticosteroid therapy resulted in improved renal function without increased rates of rejection, when compared with a higher target (10-15 ng/mL).

How can immunosuppression regimens be tailored to patient-specific factors such as chronic kidney disease, autoimmune liver disease, or elevated cancer risk?

Immunosuppression strategies are often tailored to individual patient factors, including transplant indication (e.g., autoimmune disease, HCC), renal function, and special situations such as pregnancy or breastfeeding. Below are a few alternative maintenance strategies.

Patients with Renal Dysfunction

Calcineurin inhibitors can impair renal function via afferent arteriole vasoconstriction, causing ischemic injury and chronic kidney disease in up to 20% of patients. AASLD/AST 2012, EASL 2024, and AASLD/AST 2025 guidance statements consistently recommend combination therapy with tacrolimus and either an antimetabolite (e.g., mycophenolate) or an mTOR inhibitor to permit lower tacrolimus trough levels and thereby reduce calcineurin inhibitor–associated renal toxicity.

A large Korean registry study showed tacrolimus–mycophenolate had similar graft survival to tacrolimus alone but better renal outcomes. Furthermore, in patients with renal dysfunction, switching from calcineurin inhibitor to mTOR monotherapy may preserve kidney function, but benefits are seen only if done within the first 12 months post-transplant.The AASLD/AST 2025 guidance recommends consideration of early (~3 months post-transplant) conversion from CNI to, or addition of, an mTOR inhibitor to prevent progression of kidney dysfunction in liver transplant recipients.

Finally, for patients at risk of post-transplant renal dysfunction, basiliximab induction can also be used to delay the start of calcineurin inhibitor therapy.

Patients with Autoimmune Disease or at High Risk of Rejection

In patients with pre-transplant autoimmune disease or those at high risk of rejection (such as younger recipients or those with early episodes of acute cellular rejection), combination therapy with corticosteroids, a calcineurin inhibitor, and an antimetabolite is often recommended. Oral corticosteroids may continue beyond six months or be maintained indefinitely at low doses.

Patients at Elevated Cancer Risk Post Transplantation

Due to their antiproliferative effects, mTOR inhibitors are sometimes used as monotherapy in liver transplant recipients at higher cancer risk. In patients transplanted for HCC, mTOR therapy may reduce recurrence, with two meta-analyses (Grigg et al 2019 and Yan et al 2022) showing improved three-year recurrence-free survival in those within Milan criteria at time of transplant. Reflecting this, 2025 AASLD-AST guidelines give a weak, level 3 recommendation for mTOR use in these patients.

EASL 2024 guidance also recommends mTOR-based immunosuppression for patients with recurrent or de novo non-melanoma skin cancer, supported by four RCTs and a meta-analysis demonstrating reduced incidence.

Back to the Case:

The patient wasultimately transitioned to sirolimus monotherapy. His kidney function stabilized off calcineurin inhibitor therapy. He continues surveillance imaging for HCC recurrence per his transplant center’s protocol. He also undergoes monitoring for drug-related side effects including routine reassessment of his lipid panel and urine to protein creatinine ratio.

Immunosuppression in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

All immunosuppressive agents used in liver transplantation cross the placenta and reach the fetal circulation, raising concerns about teratogenicity and fetal loss. In general, calcineurin inhibitors, prednisone, and azathioprine are considered acceptable options for transplant recipients planning pregnancy (See AASLD/AST 2012 Guidance). By contrast, mTOR inhibitors and mycophenolate should be avoided—particularly in early pregnancy—because of their association with structural abnormalities in infants.

Take Home Points

- Immunosuppression is essential after liver transplantation – it prevents rejection, preserves graft function, and prolongs survival, but must be balanced against risks such as infection, metabolic complications, and drug toxicities.

- Therapy occurs in two phases – the induction phase (first month, using high-dose corticosteroids, CNIs, ± antimetabolites) and the maintenance phase (lifelong, usually CNI-based with adjuncts or alternatives individualized to patient needs).

- Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, cyclosporine) remain the backbone of maintenance therapy, though toxicity (especially renal dysfunction) often necessitates combination strategies or drug minimization.

- Immunosuppression is tailored to patient-specific risks – for example antimetabolites or mTOR-based regimens in those with kidney dysfunction, triple therapy in autoimmune disease or high rejection risk, and mTOR-based regimens in those at elevated cancer risk (HCC or skin cancer).