Pathology Pearls: Wilson Disease

Brief Case Presentation

A 24 year old male with past medical history of major depressive disorder and BMI of 29.5 kg/m2 presented to his PCP for wellness visit and was found to have elevated liver transaminases of uncertain etiology. He was referred to hepatology for further evaluation. He reports having 2-3 beers per weekend. Abdominal ultrasound showed a diffusely echogenic liver with a smooth surface consistent with hepatic steatosis. Liver biopsy and additional laboratory studies were subsequently performed.

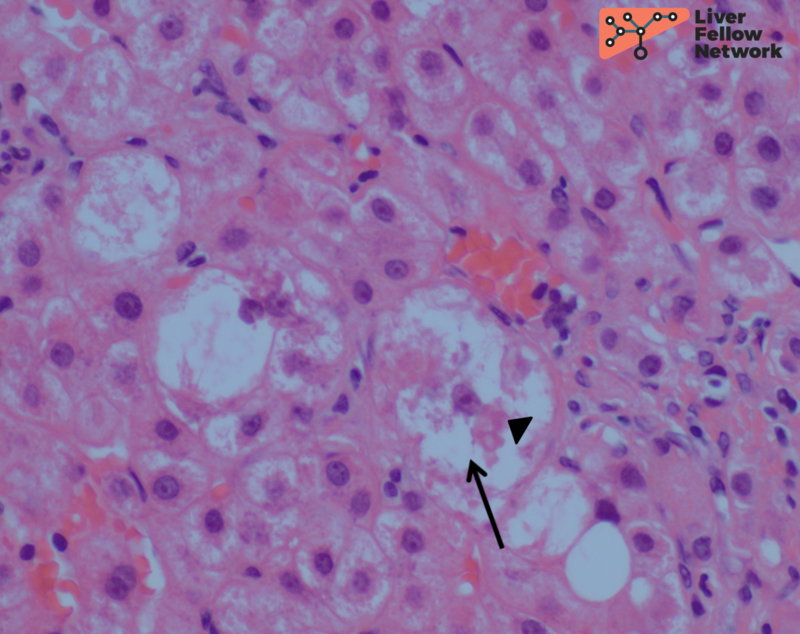

Selected lab values are as follows:

Liver biopsy findings

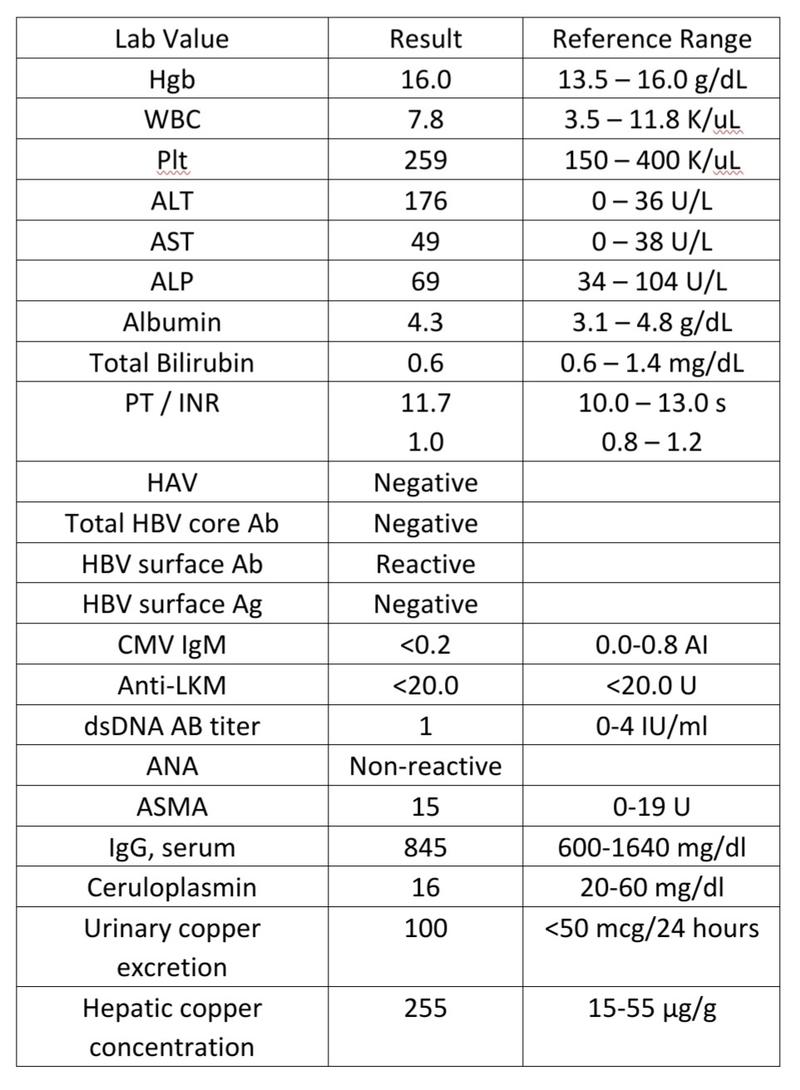

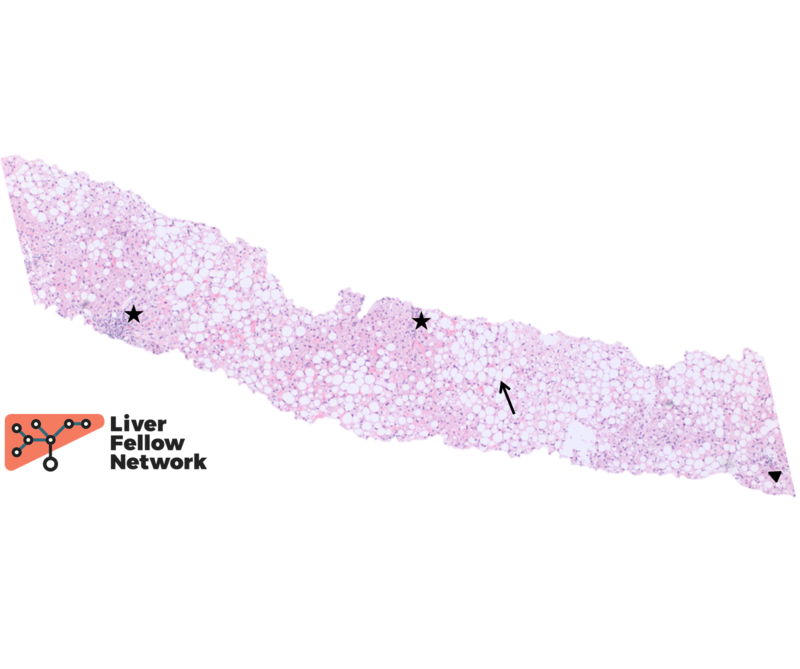

At low power, the liver core shows severe macrovesicular steatosis (~90% of hepatic parenchyma; NAS Grade 3), moderate mixed lobular inflammation (NAS Grade 2) and minimal mixed portal inflammation (Figure 1 and 2).

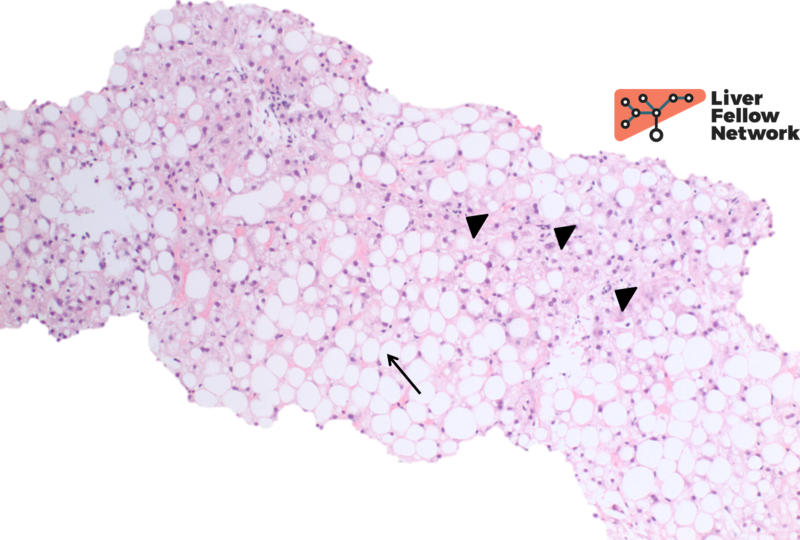

At high power there is occasional ballooning degeneration (NAS Grade 1) (Figure 3), consistent with steatohepatitis (NASH CRN NAS 6).

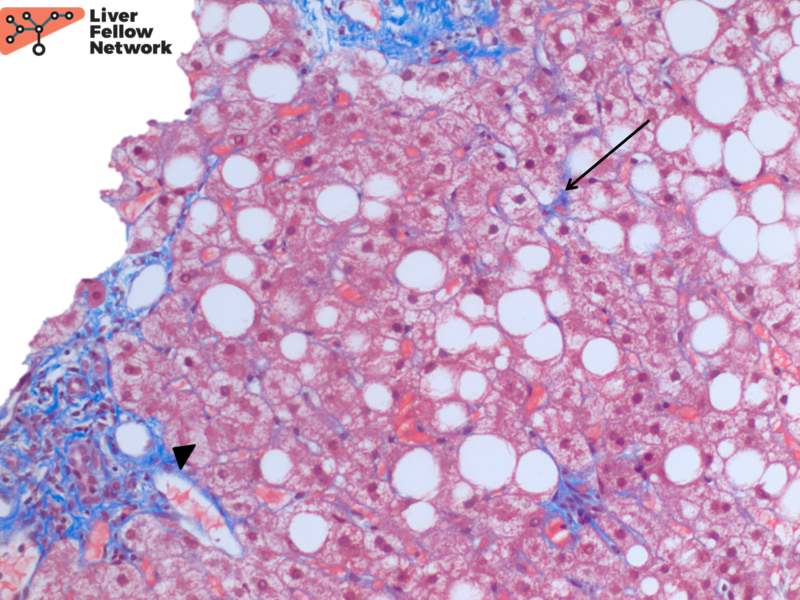

A trichrome stain highlights minimal perisinusoidal fibrosis and no significant periportal fibrosis (NASH CRN Fibrosis Stage 1a) (Figure 4).

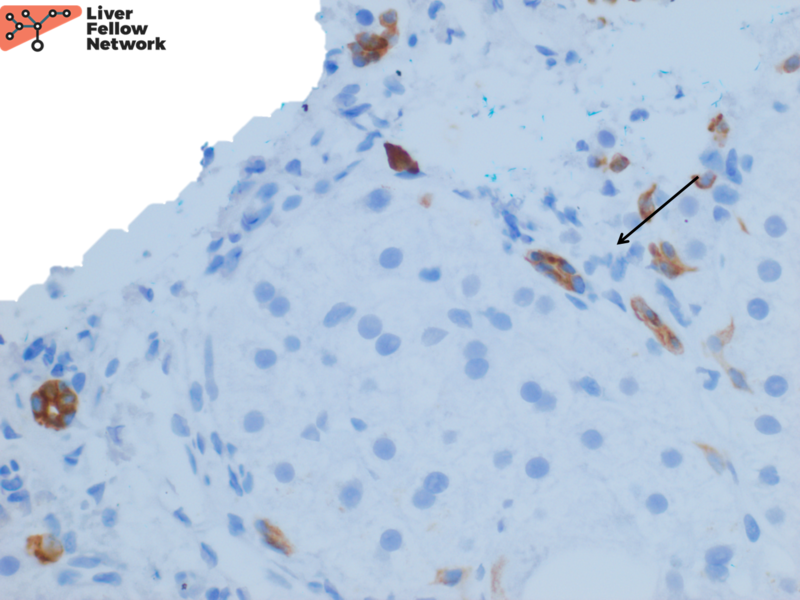

An immunohistochemical stain for CK7 demonstrates focal bile ductular proliferation (Figure 5).

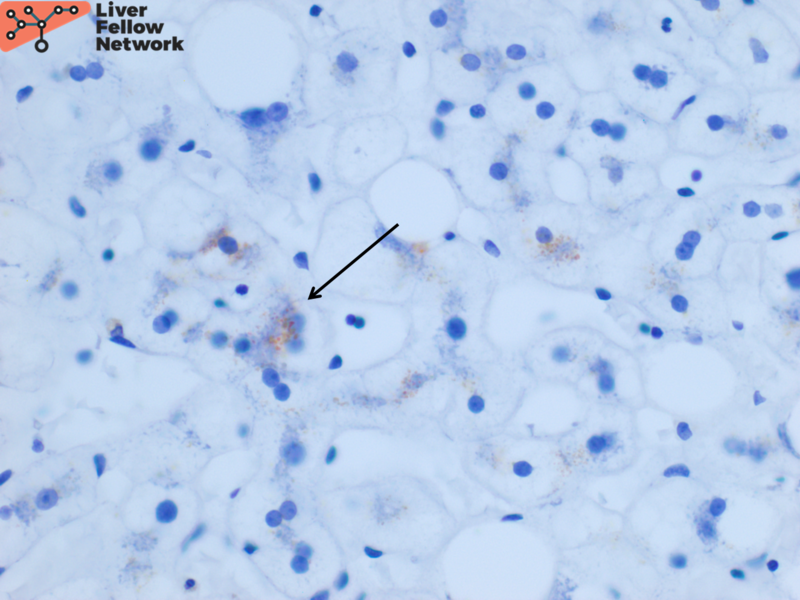

Focal hepatocellular copper is present on Rhodanine stain (Figure 6).

Quantitative hepatic copper concentration is found to be 255µg/g. In the clinical context provided, the histologic findings are compatible with Wilson’s Disease.

Etiology and Molecular Characteristics of Wilson Disease

Wilson Disease is an autosomal recessively inherited disorder characterized by a mutation in ATPB7 that encodes an ATPase-dependent, P-type copper transporter localized to chromosome 13q-14.3. This ATPase transports copper into bile for excretion. Bile being the only route of copper excretion, decreased function or absence of ATPB7 results in copper accumulation in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes. More copper also remains unbound to ceruloplasmin and subsequently precipitates in brain, eyes and kidneys. Additionally, ceruloplasmin is also low because the copper-free form released from hepatocytes in Wilson disease is rapidly degraded.

The carrier frequency of Wilson is 1 in 100 with successive generations of families being affected despite the autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Heterozygotes are known to be biochemically affected and clinically unaffected in most cases. Three hundred and seventy nine out of 500 mutations in ATPB7 are thought to be pathological.

Genetic confirmation of the disease is difficult due to large number of mutations hence a combination of histological and biochemical features help confirm the diagnosis.

Histologic features of Wilson Disease

While the histological features of Wilson are nonspecific, but when combined with clinical history they tend to fall into the following categories to prompt further workup:

- Fatty liver in a normal weight young individual- In this pattern, macrovesicular steatosis with or without ballooning, Mallory bodies and scattered glycogenated hepatocyte nuclei can be seen, overlapping with classic findings of toxic/metablic injury (NAFLD/NASH/ASH).

- Cryptogenic cirrhosis in young or middle aged adult- In this pattern, advanced fibrosis to cirrhosis is observed. Which may be accompanied by mild septal and portal chronic inflammation, lobular cholestasis with or without mild lobular inflammation, steatosis, ballooning degeneration, Mallory bodies, giant cell transformation, and granular reddish-brown deposits in periseptal hepatocytes.

- Acute unexplained hepatitis or liver failure in a young individual- In this pattern, marked lobular inflammation with hepatocyte necrosis is identified. Plasma cells and interface activity mimicking autoimmune hepatitis can be seen with or without fibrosis.

The rhodanine stain is used most commonly to display red-brown granular staining (Figure 6). Positive copper deposition tends to be zone 1 (periportal) but can be pan-lobular. Positive copper staining should be interpreted along with the biochemical laboratory features to ensure it is not from chronic cholestasis. Conversely, negative copper staining does not rule out Wilson disease. Quantitative copper analysis can be performed on fresh or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) liver biopsy tissue.

This is often a send-out test for pathology laboratories and reference labs have specific tissue requirements. If Wilson disease is in the differential discuss with your hepatopathologists prior to biopsy in order to ensure enough liver tissue is obtained for successful workup.

Differential Diagnosis for Wilson Disease

A number of copper overload diseases outside of Wilson come under the differential diagnosis including any cause of chronic cholestasis as aforementioned. Amongst others are, Indian childhood cirrhosis, Tyrolean infantile and idiopathic copper toxicosis. Despite copper overload, these diseases often present with cirrhosis. The precirrhotic histology of all of these diseases is similar and not well understood. However, they do not have mutations in ATPB7 and low ceruloplasmin.

References

- Torbenson, Atlas of Liver Pathology: A Pattern-Based Approach. 2019

- Torbenson, Surgical Pathology of the Liver. 2018.

- Burt, MacSween’s Pathology of the Liver: Seventh Edition. 2017.

- Odze and Goldblum, Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas: Third Edition. 2014

- Washington, Liver in Wilson Disease. 2017