What’s the deal with viral hepatitis vaccination?

Viral hepatitis has been and remains a formidable global health challenge. To effectively combat this, we employ a powerful tool: vaccinations. In this discussion, we will delve into the intricacies of viral hepatitis and carefully examine the recommendations for vaccination across different patient groups with the goal of helping to elucidate the understanding of why viral hepatitis vaccinations still matter.

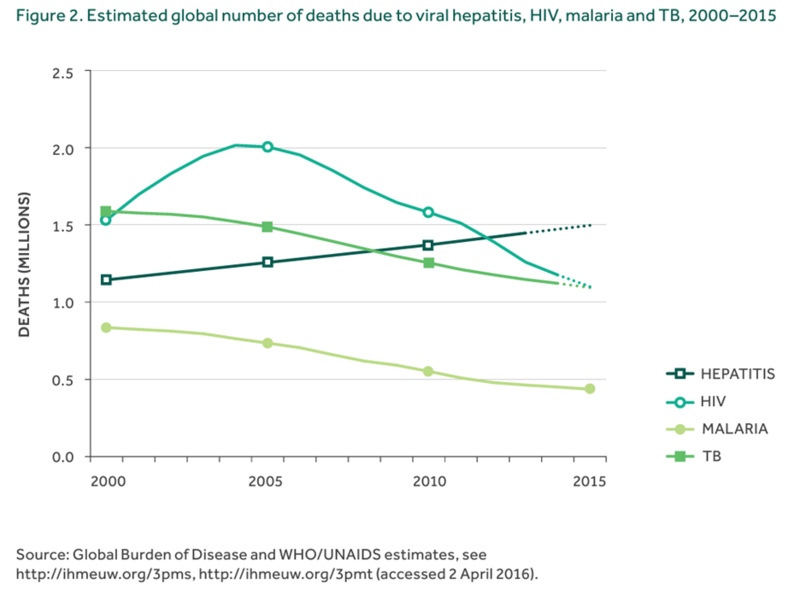

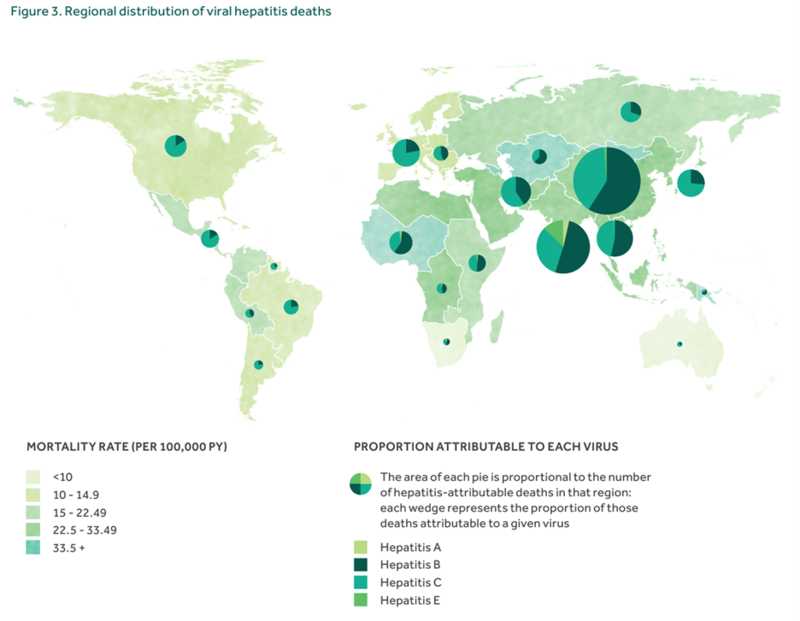

The WHO has established a goal and strategy to eliminate viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030. This strategy, while addressing all five viral hepatitis viruses, focuses mainly on HBV and HCV given their public health burden. There remains significant morbidity and mortality associated with viral hepatitis that is growing in comparison to other infectious diseases.

Figure 1.Global burden of disease for major infectious diseases. Figure from WHO

Figure 2. Global burden of viral hepatitis related deaths from the WHO

Hepatitis A (CDC Reference)

Okay quick refresh – remind me, which is A, again?

Hepatitis A is one of those diseases you might see a test question about but are probably not going to see in inpatient medicine. That’s great because typically it’s mild and self-limited. It presents similarly to other viral hepatitis infections with vague symptoms including fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, and abdominal discomfort, followed within a few days to a week by dark urine, pale stools, and jaundice. HAV has an incubation period of around 28 days with peak transmission before the onset of jaundice.

How do we get it?

Hepatitis A is transmitted from the fecal-oral route either form person-to-person transmission or contaminated food or water.

Where is it typically seen?

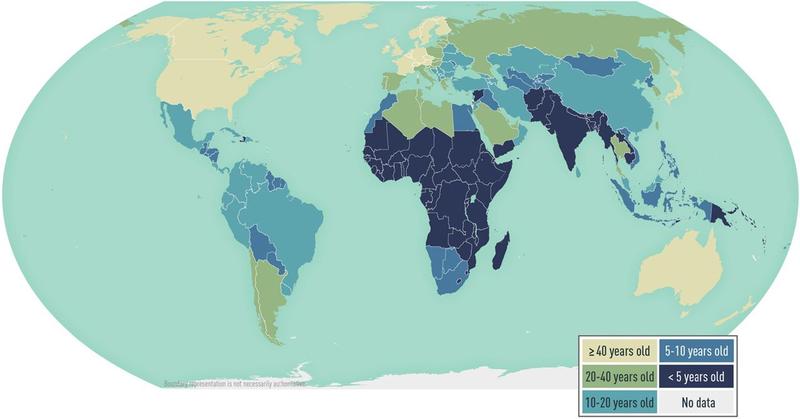

In highly endemic areas such as parts of Africa and Asia, many people likely get infected with HAV as children and are immune as adults. Fortunately, the incidence of HAV is decreasing globally while the age at midpoint of population immunity (AMPI - the youngest age at which half of the birth cohort has serologic evidence of prior exposure to hepatitis A virus) is increasing.

Figure 3. Estimated age at midpoint of population immunity (AMPI) to hepatitis A, by country. Image from CDC Yellowbook, adapted from Jacobsen 2018

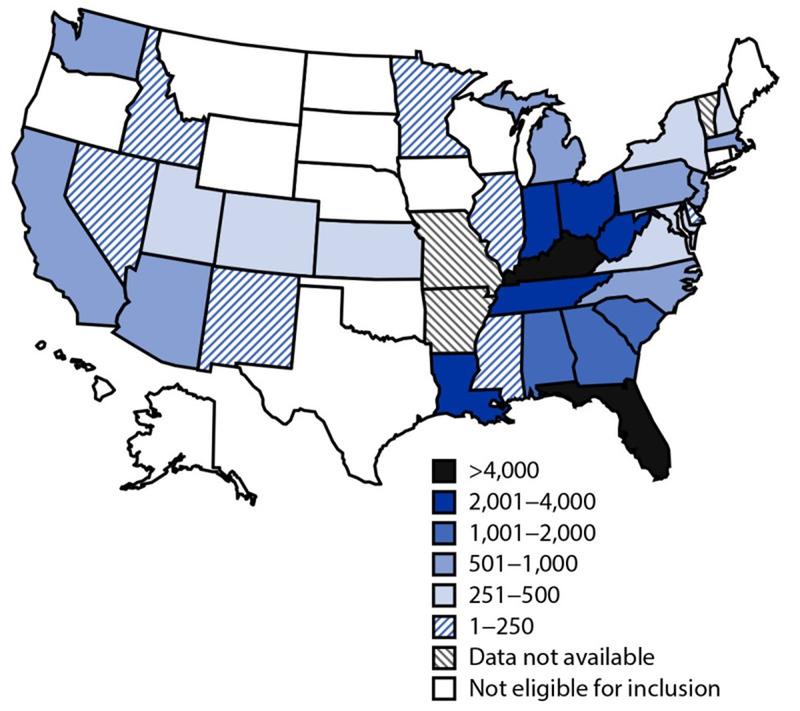

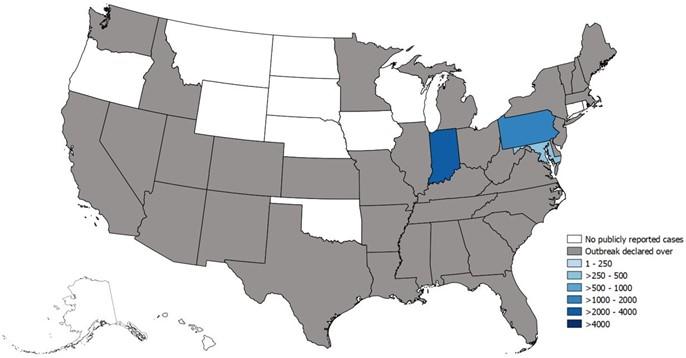

In the US, we typically see HAV in people who have recently traveled to an endemic country or from consuming raw seafood. There have been outbreaks across 37 states in the US since 2016 involving approximately 44,650 cases, 27,250 hospitalizations, and 425 deaths.

Figure 4. Map of HAV outbreaks as of October 6, 2023. Image from the CDC.

Figure 3. Cumulative outbreak-associated hepatitis A cases reported, by state* — United States, August 1, 2016–December 31, 2020. Image from MMWR.

Okay but if HAV is so mild, why vaccinate at all?

In high-risk populations, such as the elderly and persons with chronic liver disease, HAV can be severe and even lead to fulminant liver failure resulting in the need for transplantation or leading to mortality.

Prolonged and relapsing HAV has been documented as well in 10-15% of infected persons, though fortunately there is no evidence of chronic HAV.

What’s the history of HAV vaccine development?

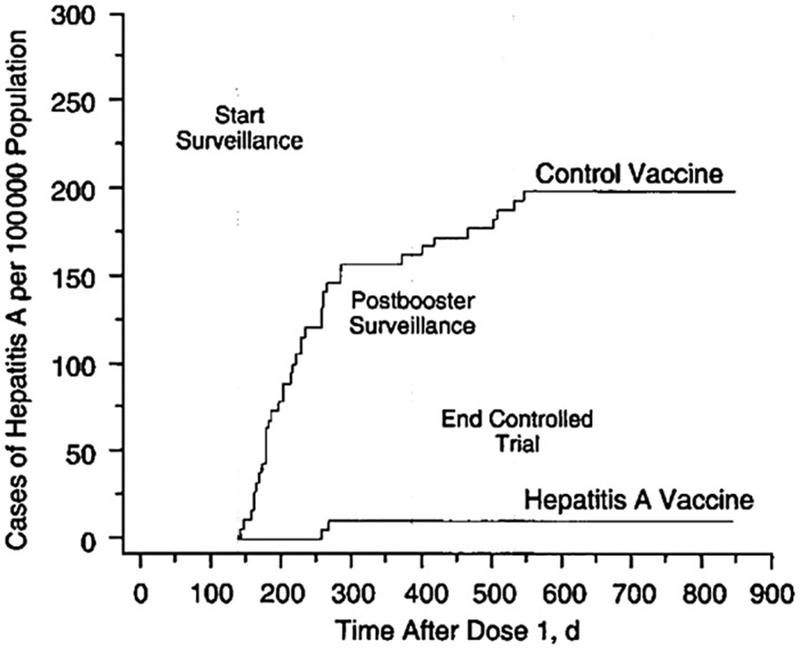

By 1945, researchers had demonstrated passive immunization with serum immunoglobulin could be administered effectively for postexposure prophylaxis against HAV postexposure prophylaxis against HAV Subsequent trials led to the development of the HAV vaccinations. The GlaxoSmithKlein (GSK) vaccine (HAVRIX) and the Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) vaccine (VAQTA) were licensed in the mid‐1990s in the United States and worldwide. One study of efficacy of the GSK vaccine in Thailand demonstrated a protective efficacy rate against HAV before and 5 months after a 1‐year booster was 94% and 99%, respectively, without serious adverse events.

Figure 5. Cumulative rates of symptomatic infection with HAV in the hepatitis A vaccine and control group trial in Thailand. Innis BLSR, Kunasol P, et al. Protection against hepatitis A by an inactivated vaccine. JAMA 1994;271:1328‐1334.

When did we start vaccinating?

For HAV, there was a gradual increase in recommendation to vaccinate in the United States beginning in 1996 in certain areas of high incidence. The guidelines expanded until 2006 when the recommendation became ubiquitous for children and resulted in a 95.5% decrease in reported hepatitis A cases.

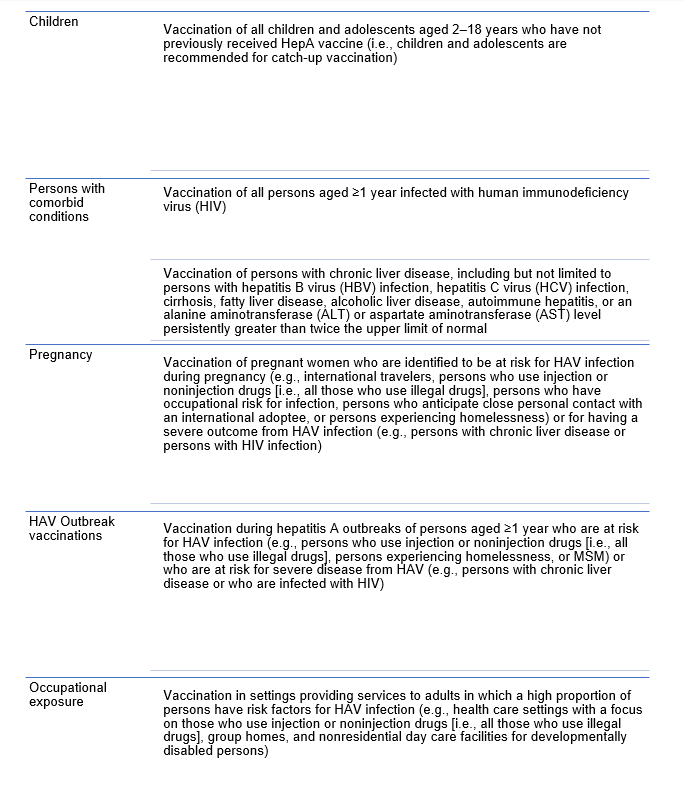

Got it, now who gets vaccinated?

Children 12 months to 23 months in the United States get vaccinated. If a child has not received the HAV vaccine, it is recommended to vaccinate children 2 to 18 years old.

For adults, however, there is not a blanket recommendation, but rather those at “high risk.” This is in part because HAV is typically mild and self-limited and thus poses severe risk in only a small portion of the population, namely those who are immunocompromised, advanced age (according to the CDC this is age above 40!), with underlying medical conditions (read: vague, but seems on review just to reference HIV), or with chronic liver disease.

What about people exposed?

The CDC recommends post exposure prophylaxis with HAV vaccine for unvaccinated persons and HAV IgG for select groups. IG should be used for infants under a year old, immunocompromised persons, persons who have chronic liver disease, and persons for whom vaccine is contraindicated. IG is also preferred over hepatitis A vaccine for persons aged >40 years; however, vaccine may be used if IG cannot be obtained.

What are the travel recommendations?

Hepatitis A travel recommendations can be found here. While anyone traveling to an area with endemic HAV is at risk, those who visit rural areas with poor sanitation are higher risk.

You can also look specific locations up on the CDC Travel Destinations website.

Hepatitis B (CDC Reference)

Okay quick refresh – remind me, which is B, again?

Symptoms are similar to HAV and range from mild to fulminant liver failure (<1%). The average incubation period is 60 days from exposure to onset of abnormal serum ALT levels and 90 days from exposure to onset of jaundice. In contrast to HAV, however, HBV can lead to chronic infection. Chronic infection occurs among 80%–90% of persons infected during infancy, 30% of persons infected before age 6 years, and <1%–12% of persons infected as an older child or adult. Around one-quarter of persons who acquire chronic HBV as a child and 15% who acquire as an adult will die prematurely from cirrhosis or liver cancer. Treatment is supportive for acute HBV.

How do we get it?

HBV is highly infectious! HBV is transmitted through percutaneous, mucosal, or nonintact skin exposure to infectious blood or body fluids including blood, semen, vaginal secretions, and even saliva, tears, and bile. Urine, feces, vomit, and sweat are less likely to be infectious vehicles without blood. HBsAg has been found in breast milk but is also unlikely to lead to transmission, and hence HBV infection is not a contraindication to breastfeeding.

What is the history of HBV vaccine development?

The vaccine that is currently recommended, HEPLISAV-B®, was developed in 2018. Prior to this there was a plasma-based vaccination that became available in the US in 1981 (no longer available) followed by recombinant vaccines in 1986. The HBV vaccine has an efficacy of over 90%. Furthermore, there are now combination vaccines for HAV/HBV!

When did we start vaccinating?

Vaccination began in 1982 and while initially incidence declined, there has been stagnation in recent years.

Got it, now who gets vaccinated?

Updated guidelines in 2022 from the CDC are included below, but notably also include ALL adults up to age 59!

Universal Vaccination of Infants, Children, and Adolescents

- All infants should receive the HepB vaccine series as part of the recommended childhood immunization schedule, beginning at birth.

- HepB vaccination is recommended for all unvaccinated children and adolescents aged <19 years

Adults

- All adults 18-59

Persons at risk for infection by sexual exposure

- Sex partners of HBsAg-positive persons

- Sexually active persons who are not in a mutually monogamous relationship [>1 sex partner during the previous 6 months]

- Persons seeking evaluation or treatment for an STI

- MSM

Persons at risk for percutaneous or mucosal exposure to blood

- Household contacts of HBsAg-positive persons

- Residents and staff of facilities for developmentally disabled persons

- Health care and public safety personnel with reasonably anticipated risk for exposure to blood or blood-contaminated body fluids

- Hemodialysis patients and predialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and home dialysis patients

- Persons with diabetes mellitus aged <60 years and persons with diabetes mellitus aged ≥60 years at the discretion of the treating clinician

Persons at risk given comorbid diseases

- Persons with HCV infection

- Persons with chronic liver disease

- Persons with HIV

Persons at risk given location

- International travelers to countries with high or intermediate levels of endemic HBV infection

- Incarcerated persons

Persons with a history of current or recent IVDU

Vaccination of Pregnant Women

- Pregnant women who are identified as being at risk for HBV infection during pregnancy (e.g., having more than one sex partner during the previous 6 months, been evaluated or treated for an STI, recent or current injection-drug use, or having had an HBsAg-positive sex partner) should be vaccinated.

Do we do post-vaccination testing?

Testing for anti-HBs after vaccination is recommended for the following groups for the purpose of booster or revaccination:

- Infants born to HBsAg-positive women and infants born to women whose HBsAg status remains unknown (e.g., infants safely surrendered shortly after birth).

- Healthcare workers and public safety workers at risk for blood or body fluid exposure

- Hemodialysis patients

- HIV-infected persons, and other immunocompromised persons (e.g., hematopoietic stem-cell transplant recipients or persons receiving chemotherapy)

- Sex partners of HBsAg-positive persons

What about non-responders? Is this a thing we have to worry about?

The immune response to HBsAg can vary in healthy individuals with 5-10% of individuals not mounting a response of titre of at least 10 IU/L (adequate is considered a titre over 100 IU/L). One study demonstrated 89% persistent immunity up to 17 years after vaccination. Several hypotheses have been generated to explain this phenomenon. The main clinical take away, however, is that they are considered non-immune. Management of these persons can include frequent screening for new infection, as well as attempt at additional immunizations.For healthcare workers who are at increased risk, testing titer levels is especially important. Studies have shown that immunocompromised persons likely have a need for a booster dose. In 2004 a global Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board met and determined that while there is no current evidence to support boosters in immunocompetent persons, the impact of those at risk from sexual exposure or healthcare exposure is not currently known. Moreover, patients with cirrhosis are less likely to mount a full immunologic response to vaccination, with low antibody titers. Those with chronic liver disease with or without cirrhosis are more likely to develop hepatic decompensation with infection.

What about people exposed?

For vaccinated individuals, no postexposure prophylaxis is needed. For unvaccinated individuals or those who did not respond to vaccination, vaccination and HBIG is recommended is recommended.

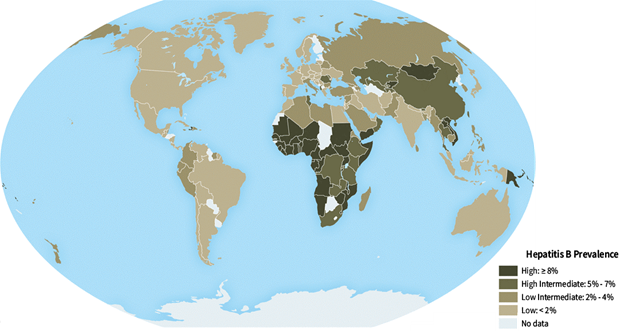

Travel recommendations?

Hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for all unvaccinated travelers under 60 years old and is also recommended for travelers 60 years and older going to a country where hepatitis B virus infection is common. Hepatitis B occurs in nearly every part of the world but is more common in some countries in Asia, Africa, South America and the Caribbean.

To check for country specific recommendations, please check out the CDC Travel Recommendations.

Figure 6. Global prevalence of HBV. Source: CDC Yellow Book 2020.

Thanks for the refresher, but we probably already do this right?

Bad news – we’re bad at screening as well as vaccinating. This can be a simple but potentially lifesaving intervention when providers remember to screen and vaccinate.

Anything else?

Yes, actually. Universal vaccination efforts against HBV have had a significant impact not only in preventing HBV, but also in reduction of incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma!

Hepatitis C

What is it?

HCV is a single RNA virus transmitted through contact with blood products such as contaminated needles, sexual transmission, vertical transmission. HCV is estimated to be affecting about 62 million people worldwide. Fortunately, there are effective treatment options for HCV.

Is there a vaccine?

No vaccine or post-exposure prophylaxis are currently available for HCV. While development and promise of an HCV vaccine is on the horizon, there are many significant challenges that remain. Barriers include the lack of economic incentive for vaccines, technical limitations to culturing HCV culture in vitro (generation of a live-attenuated or inactivated whole HCV vaccine are challenging given adaptive mutations enhancing replication in vitrio, undefined HCV virulence factors, and poor replication in nonhuman cells), viral genetic diversity, limited animal models and at-risk populations for testing vaccines, and an incomplete understanding of protective immune responses.

Hepatitis D and E

Hepatitis D (HDV) is transmitted through bloodborne contact and only occurs in those already infected with HBV. Currently, there is no curative treatment for HDV. As such, the main focus on prevention is through prevention of HBV. To learn more about HDV, check out this Why? Series post.

Like HAV, Hepatitis E (HEV) is a food- and water-borne infection that can result in acute outbreaks in communities with unsafe water and poor sanitation. Also similarly, it does not result in chronic infection or chronic liver disease in healthy individuals, though can become chronic in immunocompromised hosts. HEV can result in fulminant liver failure in pregnancy, particularly when infection occurs in the 2nd or 3rd trimesters, with HEV Genotype 1 carrying the highest risk. Prevention is through improved sanitation and food safety. While there is a vaccine for HEV that has gone through clinical trails in healthy adults, it’s use is not widespread and it has not been tested in other population such as children or persons with liver disease. The vaccine, which has existed for over a decade, has not been submitted by the company for pre-qualifications by the WHO. Further studies are needed as well as further familiarization for public health outbreak responses.

Key Points

- HAV vaccination for adults is advised for those at "high risk," including individuals who are immunocompromised, older than 40, with HIV, or have chronic liver disease.

- Hepatitis B (HBV) vaccination for adults is recommended for a wide range of individuals, including those at risk of sexual exposure, healthcare workers and those at risk of percutaneous or mucosal exposure to blood, persons with comorbid diseases such as chronic liver disease or HIV, persons who use IV drugs, and travelers to endemic regions. Relatively new guidelines suggest vaccinating all adults 19-59.

- While there is no vaccine or post-exposure prophylaxis for hepatitis C (HCV) currently available, there is ongoing research and development to address this gap.

- Hepatitis D (HDV) is a concern for those already infected with HBV, and prevention focuses on preventing HBV.

- Hepatitis E (HEV) is a food- and water-borne infection, and while a vaccine exists, it is not widely used and needs further study, especially in specific populations.